Growing Distortions in the Hometown Tax Scheme

August 28, 2023

R-2023-026E

The quantitative success of a novel scheme to redirect tax revenue from Japan’s richest municipalities to outlying regions is producing a distorting effect, notes economist Hideaki Hirata, as urban governments seek to stem the fiscal outflow by luring “hometown tax” donors with high-end gifts.

* * *

Furusato nozei, or “hometown tax,” was launched 15 years ago in 2008 as a novel donation scheme to bolster the economies of Japan’s outlying regions by enabling taxpayers to make donations to their hometowns or other locales in return for tax exemptions in the municipalities where they reside. The scheme has undergone various changes over the years, with around 45 million donations totaling approximately ¥830 billion being made in fiscal 2021. These figures are expected to continue to grow, but the scheme has recently drawn scrutiny for triggering what could evolve into unhealthy competition among local governments for taxpayer donations.

In the following, I overview the hometown tax mechanism and developments to date and look at the reasons behind the growing dissent, focusing on the impact the scheme is having on the tax revenues of urban and rural municipalities.

History of the Hometown Tax

The hometown tax is intended as a mutual support mechanism enabling taxpayers to express their financial support for their hometowns and other municipalities and giving them the funds with which to realize various initiatives, according to the April 1, 2018, “Minister of Internal Affairs and Communications Notification on Sending Return Gifts. Etc., Related to Hometown Tax.” With Japan facing serious population decline, the government expects the scheme to play an important role in making the most of local resources and reviving local economies.

From the perspective of those utilizing the scheme (that is, the taxpayers), it enables them to divert some of their local taxes to a municipality of their choice. There is no requirement that the recipient municipality actually be the hometown of or even a place visited by the taxpayer; it can be nearby or far away. This means, though, that the municipality where the taxpayer lives loses in tax revenue the amount given as a “hometown” donation by its residents. And at the same time, the municipality where the taxpayer does not live gains in tax revenue the amount given as a “hometown” donation by its nonresidents.

While the amount of hometown taxes has continued to grow, it was low when the scheme was first launched. The turning point came in fiscal 2015, when the government doubled the deduction limit and introduced a one-stop exemption system, sending hometown tax donations soaring.

Among the various incentives to donate, the key to the scheme’s popularity has been the gift—usually a local product—that taxpayers can receive from the recipient municipality. This triggered a fierce competition in the value of return gifts until an upper limit of the value was set in June 2019 at no more than 30% of the donation. This initially dampened the growth in the amount donated. But from the taxpayer’s perspective, 30% was better than nothing, and the amount of donations soon began to grow again—this time with municipalities competing among one another within the 30% limit.

The scheme, after a lackluster start, can now probably be said to be entering its third phase of growth; the first was the period following the doubling of the deduction limit in 2015 and the introduction of the 30% rule in June 2019. What sets the current phase apart is that whereas the two earlier phases more or less achieved the stated aim of the scheme—to shift tax revenue from urban to rural areas—urban municipalities have now begun to “fight back” with gifts of their own to stem the outflow.

Major Revisions in 2015

Let us now take a closer look at the revisions enacted in 2015, which raised the incentive for using the hometown tax scheme in three ways.

First, the scheme’s framework was doubled, raising the economic incentive for all taxpayers (incentive 1). Previously, the hometown tax donation cap for a household with one dependent spouse earning ¥3 million was ¥12,000, according to an estimate by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, but the 2015 revision raised the limit to ¥23,000 yen. In the case of a household earning ¥7 million, the cap jumped from ¥55,000 to ¥108,000.

This cap, in concrete terms, represents the amount that can be deducted from what one owes in annual income and local inhabitant taxes. Taxpayers can pay (donate) beyond the cap, but this will be treated as a donation with a return gift and without a tax deduction. Since taxpayers are not obliged to pay any amount above the cap, most people use the hometown tax scheme with the limit in mind.

This revision had a particularly big impact on high income earners (incentive 2); the national and local income taxes are progressive, so the cap rises exponentially with income. Once the cap was doubled, the benefits became too obvious to ignore. In the above example, a 2.33-fold increase in income from ¥3 million to ¥7 million raised the cap 4.58-fold—from ¥12,000 to ¥55,000—the difference being due to the progressive nature of income taxes. With the doubling of the cap, the difference between the two income levels in what can be donated jumped from ¥23,000 (¥55,000 minus ¥12,000) to ¥85,000 (¥108,000 minus ¥23,000).

For a household with income of ¥10 million, the cap doubled to ¥171,000 (with return gifts worth up to ¥51,000); an income of ¥15 million raised the cap to ¥395,000 (¥119,000 in gifts); an income of ¥20 million resulted in a cap of ¥569,000 (¥171,000 in gifts); and an income of ¥25 million yielded a cap of ¥855,000 (¥257,000 in gifts).

A second major revision to the hometown tax scheme was the introduction a one-stop payment system enabling taxpayers to make donations without submitting a tax return. For those who normally do not file returns—such as salaried workers and low-income earners—the need for additional paperwork to benefit from the scheme was a high hurdle to clear. For this group, doing away with the filing requirement significantly enhanced their incentive to make a hometown donation (incentive 3).

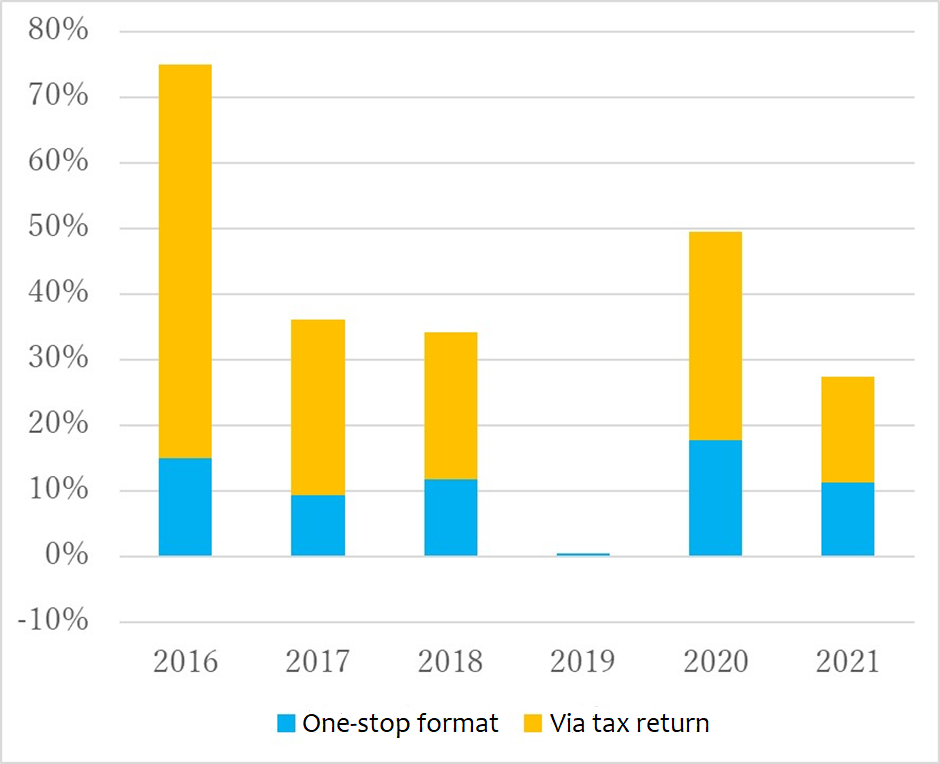

Figure 1 breaks down the contributions to the growth of hometown taxes by the one-stop format and the tax return system. The figure shows that the one-stop system has improved donor convenience and boosted the amount of hometown tax paid every year by at least 10% with the exception of fiscal 2019.

Contributions to the Growth of Hometown Taxes (Number of Donations by Type of Payment)

Source: Municipal Tax Policy Division, Local Tax Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Current Status of Hometown Tax Survey Results.

Emergence of Portal Websites and Lack of Change in Municipalities Reaping Substantial Benefits

Return gifts were not a prominent feature of hometown tax donations from the very start but grew in importance only after entering the first phase of growth, triggered by the doubling of deductions in 2015. The initial slow pickup was caused by a range of factors, but primary among them was the “scattered” nature of information provided by each municipality and the inconvenience of payment. Back then, the standard practice was for the taxpayer to access each municipality’s website and make the hometown tax payment into the bank account of a financial institution located in that municipality. Asking taxpayers to access all the websites of the more than 1,700 villages, towns, cities, and prefectures in Japan was not realistic, though. And having to pay bank transfer fees and registering an address separately for each local government also dampened taxpayers’ incentive to make a donation.

Broadening the scheme required the consolidation of each locality’s information and facilitation of payment. The solution was the introduction of portal websites, which led to rapid growth in donations and has, from around midway in the first growth phase, spurred intense competition among the municipalities for the most attractive return gifts. Enabling taxpayers to view the hometown tax info of all municipalities at a glance and offering multiple payment options (including credit cards and cashless payment) made donations far easier.

Portal websites have continued to evolve to facilitate use of the scheme even after the 30% rule was applied to curb excessive competition during the second growth phase. Their presence has grown to a point where municipalities, critics say, are forced to set aside a portion of hometown tax revenues to cover usage fees—about 10% of hometown tax revenues on average, with the share varying across municipalities.

Another issue is that the site has likely helped some municipalities reap substantial benefits from the scheme at the expense of less competitive localities. For example, there were only 71 different municipalities ranking among the top 20 in hometown tax revenues over the eight years from fiscal 2014 to 2021; the city of Miyakonojo in Miyazaki Prefecture made the list during all eight years, while Nemuro in Hokkaido and Kamimine in Saga Prefecture ranked in the top 20 in all but one year. Regions without primary products that taxpayers find attractive as return gifts, on the other hand, find themselves at a severe disadvantage. There is thus a tendency for hometown tax revenue to flow to a limited number of municipalities year after year.

Urban Pushback

The scheme’s winners may have become more or less fixed over the years, but the pattern of entrenchment is even more pronounced among the scheme’s losers—the municipalities seeing the greatest outflow of tax revenue to other municipalities. The 20 municipalities that have suffered the biggest losses have remained almost unchanged over the past four years. There are only 21 separate names on those lists, all of them either “ordinance-designated cities” (major cities with populations of at least 500,000 performing some functions of prefectural governments) or Tokyo’s 23 city-level special wards.

As I have noted above, the hometown tax scheme now appears to be entering a third phase, one in which urban municipalities that have watched their tax revenue erode over the last several years are offering return gifts of their own to stem the outflow. In other words, urban areas have begun pushing back, making the most of their unique strengths to reap benefits from the hometown tax scheme. Their hometown tax inflows might currently be well below their outflows, as the table below indicates, but efforts are actively being made to close that gap.

Hometown Tax Revenue Inflows in Municipalities with the Greatest Outflows (FY2022)

|

|

Outflow |

Inflow |

|

Yokohama |

¥23.0 billion |

¥340 million |

|

Nagoya |

¥14.3 billion |

¥220 million |

|

Osaka |

¥12.4 billion |

¥270 million |

|

Kawasaki |

¥10.3 billion |

¥930 million |

|

Setagaya Ward |

¥8.4 billion |

¥110 million |

Source: Municipal Tax Policy Division, Local Tax Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Survey on the Current Status of Hometown Tax

The policies of Tokyo’s 23 special wards toward the hometown tax scheme have been quite varied. First, some—Koto, Nerima, Shinjuku, Edogawa, Toshima, and Chiyoda—did not offer any gifts at all for the donations they received, apparently seeing few benefits to such an arrangement compared to the costs. But Shinjuku has recently begun to rethink its policy. Second, the wards that do provide return gifts can be categorized into those with standard offerings and others taking a more proactive approach with high added-value products, such as pricey assorted sweets or vouchers for classy hotels and restaurants. Wards in the latter category are working particularly hard to boost inflows.

This raises an interesting question: what exactly constitutes a “local product,” which an item must be to qualify as a return gift (as set out in Article 5 of the 2019 Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Notification No. 179)? Among the definitions given are that it must either be produced within the municipality or source most of its raw materials from there. Another criterion is that the municipality account for the bulk of the value added, with key portions of the manufacturing, assembly, or other processes taking place there, or that, in case of a service, the item should not only be provided within the municipality but also have strong links with it. The high added-value products and services urban municipalities are providing apparently meet these latter criteria for a “local product.”

One should remember that most taxpayers making hometown tax donations are urban residents. Given that the whole point of the scheme is to divert tax revenue from urban areas to the countryside, the recent urban pushback could lead to a basic distortion of the scheme, as more attractive city gifts would result in funds simply moving from one big city to another. For example, a resident of Ward A in Tokyo might make a hometown tax donation to neighboring Ward B that offers dinner vouchers as a return gift, while a Ward B resident might make a hometown tax donation with an eye to receiving hotel vouchers being offered by Ward A. Municipalities do not recommend where hometown tax donations should be directed, but given the convenience of service-oriented return gifts that can be consumed locally (at a restaurant or hotel), they could easily design their schemes so that they can wind up benefiting one another. They will also be in a position to provide a full lineup of high-end gifts to attract donations from wealthy urbanites.

Another point to consider is that only about half of the amount donated actually reaches the municipality coffers—the rest being used for return gifts, shipping costs, portal site fees, and payment processing. As I have also argued elsewhere, this inefficiency is a direct result of the scheme’s basic design. Such a distortion might be tolerated if rural areas were receiving at least half the donations, but when funds are flowing from one urban district to another, the very meaning of the hometown tax scheme is lost.

Urban authorities cannot be blamed, though, for doing their best to win back lost revenue in the interest of serving their residents. They are abiding by established rules to do what is expected of them. The onus of correcting the distortions in the scheme should fall, instead, on the national government. There are reasons, though, including political considerations, for the lack of progress in that direction—a topic I would like to address in subsequent articles.