Maintain the momentum for implementing historic international tax reform

May 14, 2024

R-2023-093E

Timelines that have been revised

On December 18, 2023, the OECD updated the timeline for implementing the international tax reform agreed to by 136 countries in October 2021 (the global tax deal). The new timeline aims to finalize the text of the Multilateral Convention (MLC) implementing the deal by the end of March 2024, with a view to hold a signing ceremony by the end of June 2024. This was not the first time the timeline has been revised, resulting in postponement of implementation. Under the original plan, the MLC was to come into effect in 2023. (The OECD missed the March 2024 deadline for finalizing the text of MLC, which has not been published as of this note's publication).

One of the reasons behind this appears to have been the delay in confirming the articles in the United States. In a press interview, Mr. Pascal Saint-Amans, a former senior official of the OECD Tax Center pointed out, in essence, that if the global deal is not implemented because of the U.S. “veto,” unilateral taxes will proliferate and might create a serious trade dispute risk (Nihon Keizai Shimbun; December 12, 2023; page 5 (in Japanese)).

When the global tax deal was achieved in 2021, it was heralded in exuberant terms as "historic" or "once-in-a-century international tax reform." What is happening with the implementation of the deal now, and what are the prospects for the future? How should Japan act? This article will summarize the situation and outlook as we enter an important phase.

Why digital tax reform?

Digital businesses can cross borders without having a conventional nexus, such as an agent who has the authority to conclude contracts, or a physical presence. Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) can reduce their tax burden by placing high-value-added intangibles in group companies in low-tax countries and operating from there in market countries. European countries that felt the consensus-based approach to imposing a tax on tech companies was “painfully slow”[1] opted to introduce DSTs unilaterally after 2018.

Against this background, the global tax deal was motivated by achieving goals such as:

- Creating“the new taxing rights” to redistribute the tax base to market jurisdictions by new “nexus” (the legal basis for taxation);

- Requires large and profitable digital firms (MNEs) to pay their fair share of international tax;

- Put the floor to the “race to the bottom” of corporation tax so that governments can maintain/raise corporate tax rates; and

- Stop the proliferation of Digital Service Taxes (DSTs) and other unilateral measures.

The architecture of the global deal

Pillar I will create the new taxing rights (also known as Amount A) that would redistribute 25% of the consolidated profits (a part exceeding 10% profit margin) of large and successful multinationals (MNEs) - global revenue of over $20 billion - to market jurisdictions. 100 MNEs worldwide are expected to meet this threshold. Part of the Pillar I deal is the removal of DSTs. A new Multilateral Convention (MLC) is needed to implement Amount A.

Pillar II will introduce a 15% global minimum tax on multinational corporations with global sales of 750 million euros or more. The global minimum tax consists of the following three measures.

(1) “QDMTT” (Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax), which is imposed in the country where the MNE's subsidiary is located.

(2) “Income Inclusion Rule” (IIR): taxation in the country of the MNE's parent company.

(3) The “Under Taxed Profits Rule” (UTPR), which is a rule for taxing MNEs in countries other than those where their group companies are located.

A global minimum tax is a highly complex system imposing additional taxes until the effective tax burden rate reaches 15%, in the order of (1), (2), and (3).

US congressional backlash

The OECD missed the end-of-March 2024 deadline for finalizing the text of the MLC, making prospects for signing at the end of June uncertain. Even if signed, it must be ratified by at least 30 countries, including the U.S., to be effective.

Of concern, however, is the lack of coordination between the Republican majority in the U.S. House of Representatives in the 2022 mid-term elections and the U.S. Treasury Department (Democratic party), which is participating in international discussions.

In September 2023, a Republican delegation from the Ways and Means Committee visited the OECD and Germany and sharply criticized DSTs, stating that the United States would not support OECD international tax reform. A two-thirds majority (i.e. bipartisan support) is needed in the U.S. Senate to ratify treaties. Furthermore, some Republicans have proposed legislation that would impose retaliatory taxation.

Amount A (global deal) vs DSTs (unilateral measures)

The design and economic effects of Amount A and DSTs are significantly different, wherein Amount A is based on the principle of international cooperation, and DST is based on “home country first.” The table below illustrates the main differences.

Table: Amount A vs DSTs

|

|

Amount A |

DSTs |

|

Described in one word |

“Flagship” of the OECD Global deal |

Unilateral measures (home country first) |

|

Type of tax |

Income tax (tax on profits) |

Excise tax (tax on sales) |

|

In-scope industries/transactions |

All industries (Excluding Financial and extraction) |

E.g. provision of digital interface, targeted advertisement, search engines, social media platforms, and marketplace. |

|

Tax base |

Net profits Reallocation of tax base (25% of consolidated profits exceeding 10% profit margin) |

Gross revenue |

|

Tax rate |

National corporation tax rates |

2% (UK); 3% (France) |

|

Taxpayers (global revenue threshold) |

Over 20 billion Euros |

750 million Euros (France) 500 million Euros (UK) |

|

Legal base |

Ratification of multilateral Convention |

Enactment of National laws |

|

Complex text (200 pages) and guidance (800 pages) |

National rules |

|

|

Existing tax conventions |

Applied (Income tax) |

Outside the scope |

|

Dispute resolution |

Treaty solution is available (Art. 33, Mutual agreement procedures) |

Remedies available in national judicial systems |

|

Foreign tax credit |

Yes |

No |

Source: Author

Economists estimate economic effects of Amount A and DSTs are different (U.S. CRS (2024)):

- Amount A (profit tax) will increase tax on large and successful MNEs in market jurisdictions. The tax will be partially offset by foreign tax credit in the home of the MNEs. Thus, while the estimated overall tax burden of the MNEs might not be changed dramatically, tax revenue of MNEs home country will be reduced.

- DSTs (an excise tax) will be passed along to consumers of the market jurisdictions that impose DSTs. If this estimate is true, the tax will not be borne by businesses. Thus, are the oft-claimed arguments that DSTs will create “double taxation” unfounded? In fact, for example, Google Ads has been adding DSTs to the invoices issued to its customers in jurisdictions that have introduced DSTs.

Assessing the arguments

Why has the U.S. (Congress) been so negative about OECD digital tax reform? Why did European countries need to introduce DSTs? Let's put ourselves in the other side's shoes.

(1) Does Amount A tax disproportionally fall on US firms?

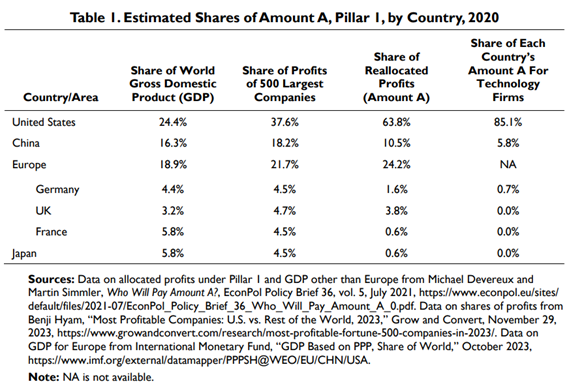

A recent report (CRS (2024)) published by a bipartisan U.S. Congressional Research Service estimates that as much as 63.8% of reallocated profits (Amount A) is attributed to U.S. firms. Since the U.S. share of profits of the 500 largest companies is only 37.6%, the reallocated tax base of Amount A is concentrated heavily on U.S. firms.

Since the estimated share of Amount A reallocated profits of firms from other countries is limited, i.e. China (18.2%), the U.K. (3.8% ), France (4.5%), and Japan (4.5%), the frustration of U.S. lawmakers and businesses that U.S. firms are being targeted is understandable in some respects.

(See annex at the end of this note for details.)

(2) Do DSTs create double taxation?

DSTs are excise taxes paid by sellers, with the tax burden passed on to consumers. Examples include tobacco, liquor, and gas taxes. Therefore, the argument that DSTs create double taxation with a tax on profit (corporation tax) may be unwarranted.

Instead, the real challenge is the compliance burden of businesses: the level of in-scope businesses for DSTs is much lower than that of Amount A. It is estimated that 100 MNEs are subject to Amount A, while 7,000 MNEs are potentially subject to DSTs globally (since these 7,000 MNEs are submitting a CbCR (Country-by-Country Report) , meaning sales exceeding 750 million Euros).

Since DSTs are not based on international agreements, it is necessary to familiarize yourself with the standards of different countries. This is a significant drawback for MNEs when conducting business across borders.

(3) Do large digital firms pay their fair share of international taxes?

A report published by the U.K. National Audit Office (NAO (2022)) summarizes the U.K.'s experience with DSTs introduced in April 2020 and releases anonymous information. According to the report, looking at the ratio of corporate income tax to UK DST for the 18 groups of companies that paid UK DST in 2020-21, 13 groups paid more DST than corporation tax, and 3 groups paid no corporate income tax at all (see NAO (2022) Fig. 9). However, given that corporation tax is not borne by loss-making firms and that DSTs are an excise tax, the economic burden of which is passed on to consumers (i.e. not paid by businesses), this does not necessarily indicate that DSTs are a backstop for corporate tax avoidance.

As US CRS (2024) summarises, “It can be argued, however, that Pillar II, which applies a global minimum tax of 15%, addresses that issue, and that the issue has also been addressed by the U.S. minimum tax on global intangible low-taxed income, or GILTI.”

Indeed, Japan introduced the income inclusion rule in the 2023 tax reform, and the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF), in which nearly 40 countries participate, has recommended that member countries adopt the rule as source countries (i.e. QDMTT). As CRS (2024) argues, a global minimum tax could help impose a fair share of tax on MNEs.

(4) Is the argument that users create value well-founded?

The UK government introduced DST in April 2020 “because it was concerned that the existing international tax system did not recognize the value being generated for digital companies through UK online users.” (UK NAO (2022), p4)

CRS (2024) argues that “this argument could become moot after Pillar I was expanded to all firms, but it could also be argued that user value creation was never a valid argument in the first place.” (summary)

However, according to Table 1 of CRS (2024), as 85.1% of Amount A of US firms are technology firms. This can be viewed from two different perspectives. On the one hand, this could mean that Amount A can appropriately tax a tax base that cannot be adequately taxed under conventional international taxation principles (value creation through user participation), and on the other (from the U.S. standpoint), it means that it is targeting digital companies.

Thriving of DSTs and other unilateral measures

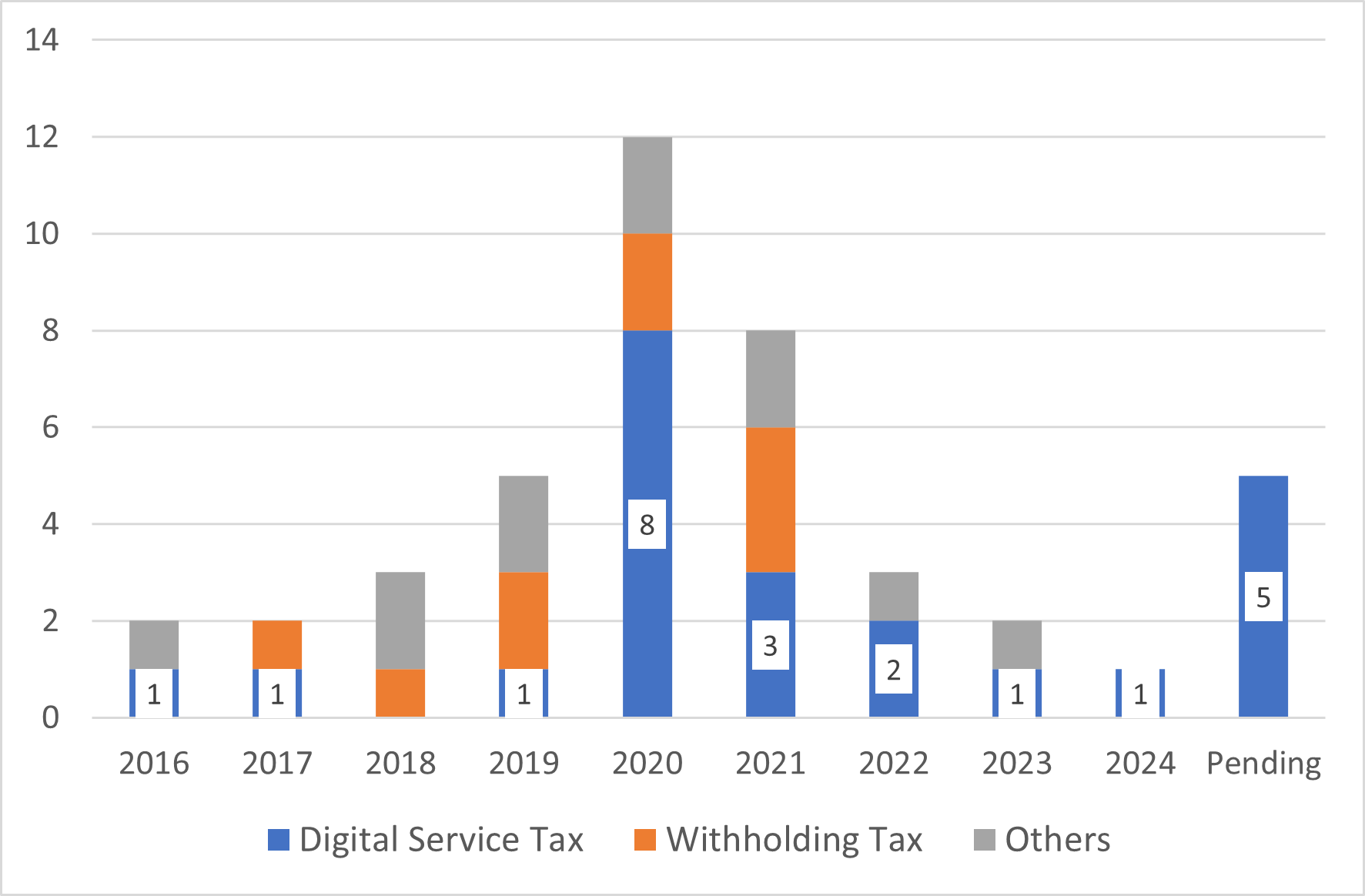

The following figure shows the number of countries that have introduced DSTs and other unilateral measures in recent years.

Source: Author, adopted from Appendix A (Selection of Digital Service Taxes), Joint Committee on Taxation “Present law and economic background relating to pragmatical manufactures and U.S. international tax policy” May 9, 2023 (JCX-8-23)

Choosing Efficient “Tools” for the Removal of DSTs: retaliation or global deal (MLC)?

The political objective of U.S. administrations is to protect the interests of U.S. MNEs from onerous taxation by other countries.

From the standpoint of MNEs operating in different countries, the key issues are predictability and compliance costs. The compliance costs for multinationals would be very high because the rules differ from country to country. The MLC would ensure predictability because taxation is based on a common standard.

Furthermore, the MLC provides for mutual consultation (Article 33) to prevent or resolve disputes, as well as procedures for seeking confirmation of taxpayer status (Article 22). Compared to the DSTs, which, in the event of a dispute, must resort to each country's judicial system, predictability is ensured for MNEs.

The political goal of the U.S. is to force a sovereign nation to give up DSTs; there is no reason to believe that economic retaliatory measures (e.g. tariffs) will effectively achieve this goal. The introduction of DSTs was an unavoidable choice for European politicians, and even if there was a risk of retaliatory tariffs, it is not something that could be easily retracted.

To begin with, the DST is an excise tax, and therefore not eligible for a foreign tax credit in the U.S. (confirmed in IRS Notice 2023-55). Thus, DSTs do not undermine the U.S. tax base (although it could increase the tax burden for U.S. MNEs if the tax burden is not passed onto consumers).

In this light, it seems clear that, from a rational and objective standpoint, a multilateral treaty approach would be more beneficial to U.S. companies. At the very least, it is elegant as a method, and in addition would not merely be beneficial to the U.S. but would also enhance the U.S. position in international taxation rulemaking.

Rationality alone cannot save us

The MLC on Amount A will not go into effect unless a bipartisan agreement is reached in the U.S. Senate, which will most likely be difficult to achieve.

As US CRS (2024) predicts, if MLC is not adopted, DSTs would be likely to remain and proliferate. A former senior official of the OECD Tax Center warned at a tax experts’ conference that unratified MLC would spark off digital tax “tsunami” (Bloomberg Daily Tax Report, April 18, 2024).

Will countries eventually pursue taxing digital firms with DSTs, which their own consumers bear? Will the U.S. resort to what it calls retaliatory taxation? If so, it would create an ironic situation in which international tax reform, which was supposed to increase predictability for MNEs, would instead create unpredictability. It is clear that both countries introduced DSTs and the US have their own rationales.

In the following, I would like to consider options for avoiding “worst-case scenario” based on international principles of cooperation.

(1) Reduce concentration in U.S. firms to promote understanding of U.S. stakeholders

As one measure (possibility), could we adjust the threshold and the percentage to be distributed so that the amount subject to Amount A is not concentrated in the U.S.?

The estimated concentration on Amount A reallocation to U.S. companies is due to the success of U.S. firms and not because of the design of the MLC. However, this rationality alone would not persuade U.S. stakeholders.

(2) Consider the use of tax-mix of existing tax (VAT)

Can't we find a solution by changing our point of view? For example, for countries that have introduced or are contemplating DST, it would be helpful to bring in a perspective of a "tax-mix" of existing and well-founded taxes to avoid a head-on collision of taxing powers of destination vs. home countries. At any rate, both VAT and DST are destination-based taxes.

The experience of the United Kingdom, a country that introduced DST, shows that VAT accounts for more than 60% of the taxes paid by a group of companies that paid DST. (see Fig. 8 of NAO (2021))

To reduce cross-border VAT leakage, countries' experiences in recent years include the following:

In July 2021, the EU introduced new VAT rules for cross-border VAT e-commerce and strengthened reporting requirements for payment services, including platforms (CESOP).

The FY2024 tax reform in Japan introduced a system whereby platforms are deemed to have provided services when imposing VAT on inbound digital services (e.g. online games) provided via the platform.

Japan’s choice: Raise high the banner of international cooperation

Governing political parties in Japan stated in their FY2021 tax reform proposal that :

Japan has consistently led the discussion on international tax reform since the launch of the BEPS project, and efforts must be made toward implementing this international agreement. The project emphasizes the promotion of the principle of international cooperation. (translation by the author)

Given the uncertainty of the outlook for when the treaty will come into force and be applied, it may be reasonably proposed that Japan should also consider the future introduction of DSTs. This proposal would stem from the need to ensure fairness and competitiveness between local and foreign digital firms.

So, what should be a plan B for Japan? From a political point of view, the answer seems apparent to me. Japan should keep a clear line of sight with the European choices. If Japan joined Europe in introducing DSTs, it would undermine its position in advocating for the removal of such unilateral taxes. Additionally, it would make it challenging to convince the U.S. that implementing an Amount A global deal would be more beneficial to everyone after all.

To tax the profits of MNEs, rather than relying on excise taxes passed on to consumers, we must ensure the successful implementation of Amount A. To this end, the participation of the U.S. is indispensable. Accordingly, it might be useful to rethink aspects of the design of Amount A, such as the threshold, to prevent the tax burden from disproportionally falling on U.S. large MNEs relative to their global profit share.

I would like to conclude by citing a comment made by Amazon, one of the largest of the digital firms. In public comments submitted to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the company stated (excerpt):

At Amazon, we understand that creating a stable international tax framework requires cooperation from all key stakeholders around the globe, including governments and the business community. We believe that only international cooperation can achieve a durable solution to these complex challenges.

Rather than detailing the draft article's shortcomings, Amazon supports a framework for international cooperation and calls for its implementation.

As a for-profit company that has thrived in the digital realm with cloud services like AWS, Amazon's pragmatic view to balancing profit and loss should be considered by many countries, including Japan and the United States.

The ‘real risk’ of the current global deal failing would not be the proliferation of DSTs or a trade war, but rather, a setback for the OECD-led international taxation order, as the Global South has a growing voice in international rulemaking. Japan, the U.S., and Europe should know that they have much to lose by doing so.

Annex:

U.S. bipartisan Congressional Research Service's report argues that the reallocated profits (Amount A) fall on U.S. firms disproportionally and shows estimated evidence:

Source: CRS (2024)

References:

CESOP: European Union, “Central Electronic System of Payment information“

CRS (2024): United Stets, Congressional Research Service “The OECD/G20 Pillar 1 and Digital Services Taxes: A Comparison”

NAO (2022): United Kingdom, National Audit Office “Investigation into the Digital Services Tax”

[1] Budget 2018: Philip Hammond's speech