U.S. Public Finances Face Surge in Interest Payments – Issues and Implications for Japan –

May 7, 2024

R-2023-086E

U.S. public finances are facing a surge in interest rates, partly due to interest rate increases to cope with post-pandemic inflation. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that interest payments will become a larger spending item than national defense in 2024, reaching $1 trillion by 2026. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, countries around the world aggressively eased monetary policy, leaving interest rates below economic growth rates for extended periods of time. These circumstances allowed greater leeway for stimulus packages, which in part backed the massive spending in the post-pandemic era. However, the recent rise in interest rates has changed the landscape of U.S. public finances. This article reviews the U.S. fiscal situation in the face of a surge in interest payments, followed by a summary of the issues. The article also states implications for Japan’s fiscal management going forward.

The Impact of Interest Rate Increases on U.S. Public Finances

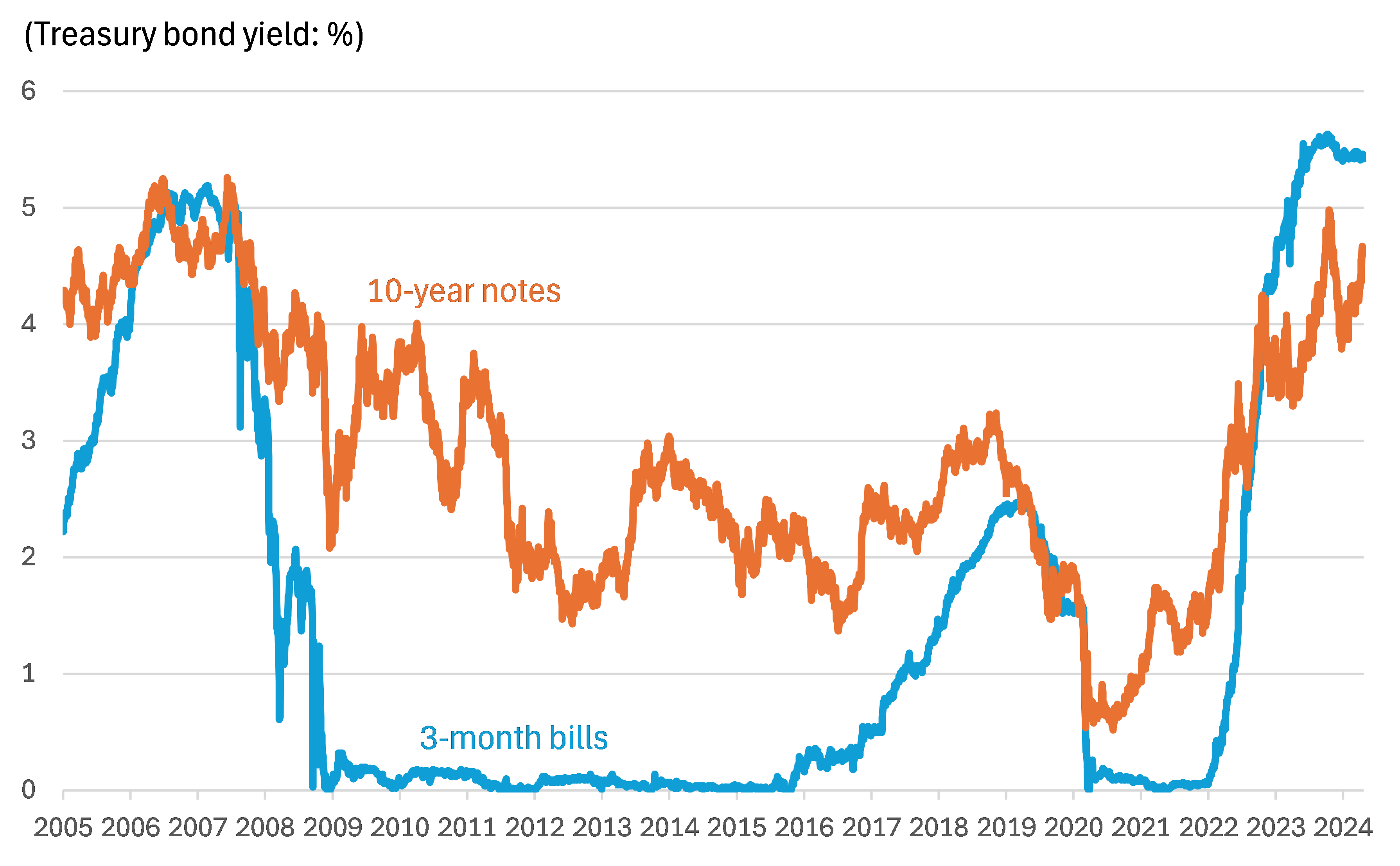

In order to address post-pandemic inflation, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board (Fed) has repeatedly raised interest rates since March 2022. As a result, in April 2024, interest rates on U.S. Treasury bond yields were about 4.6% for 10-year notes and 5.5% for 3-month bills, marking the highest levels since 2007 (Chart 1).

Chart 1 U.S. Treasury bond yields

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

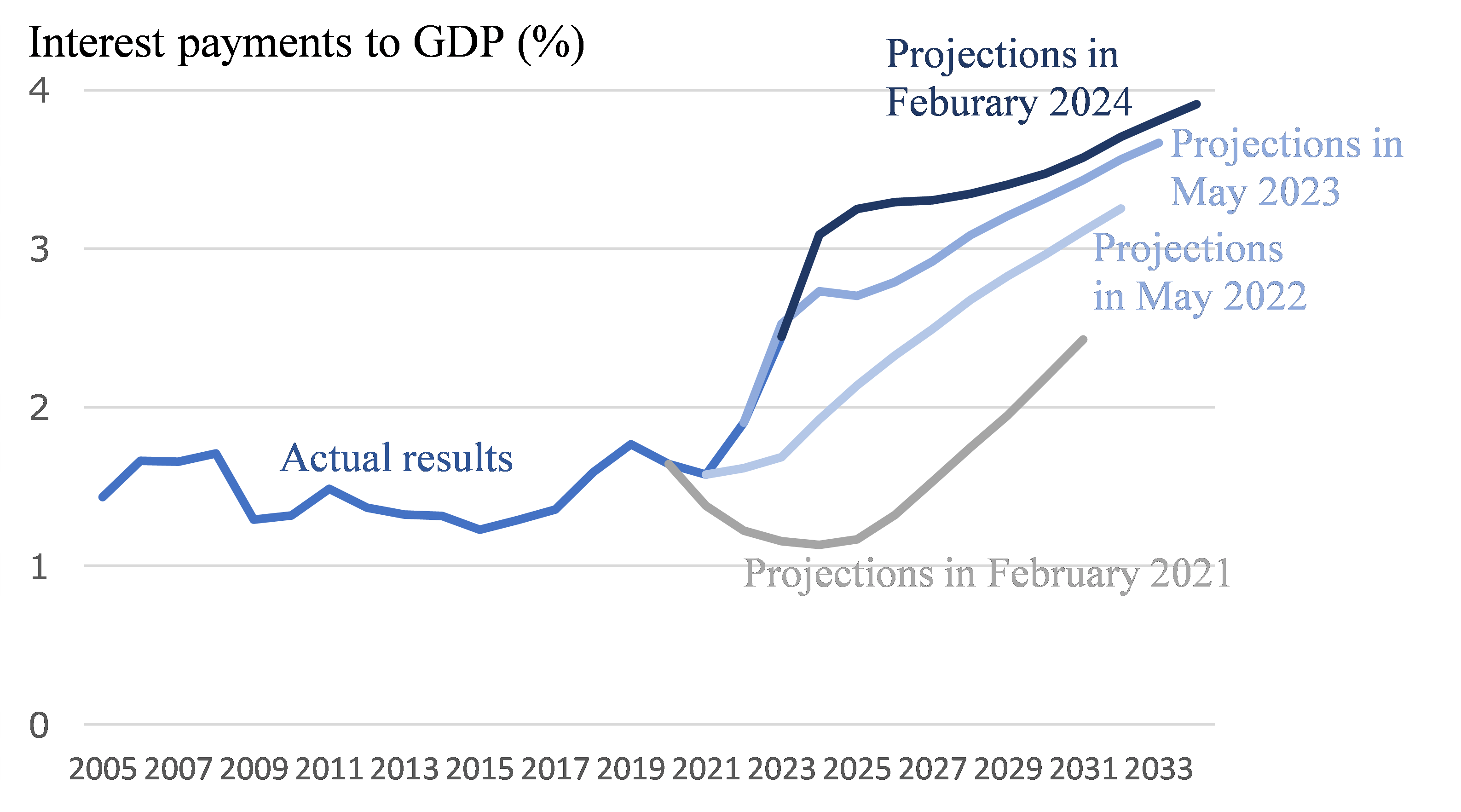

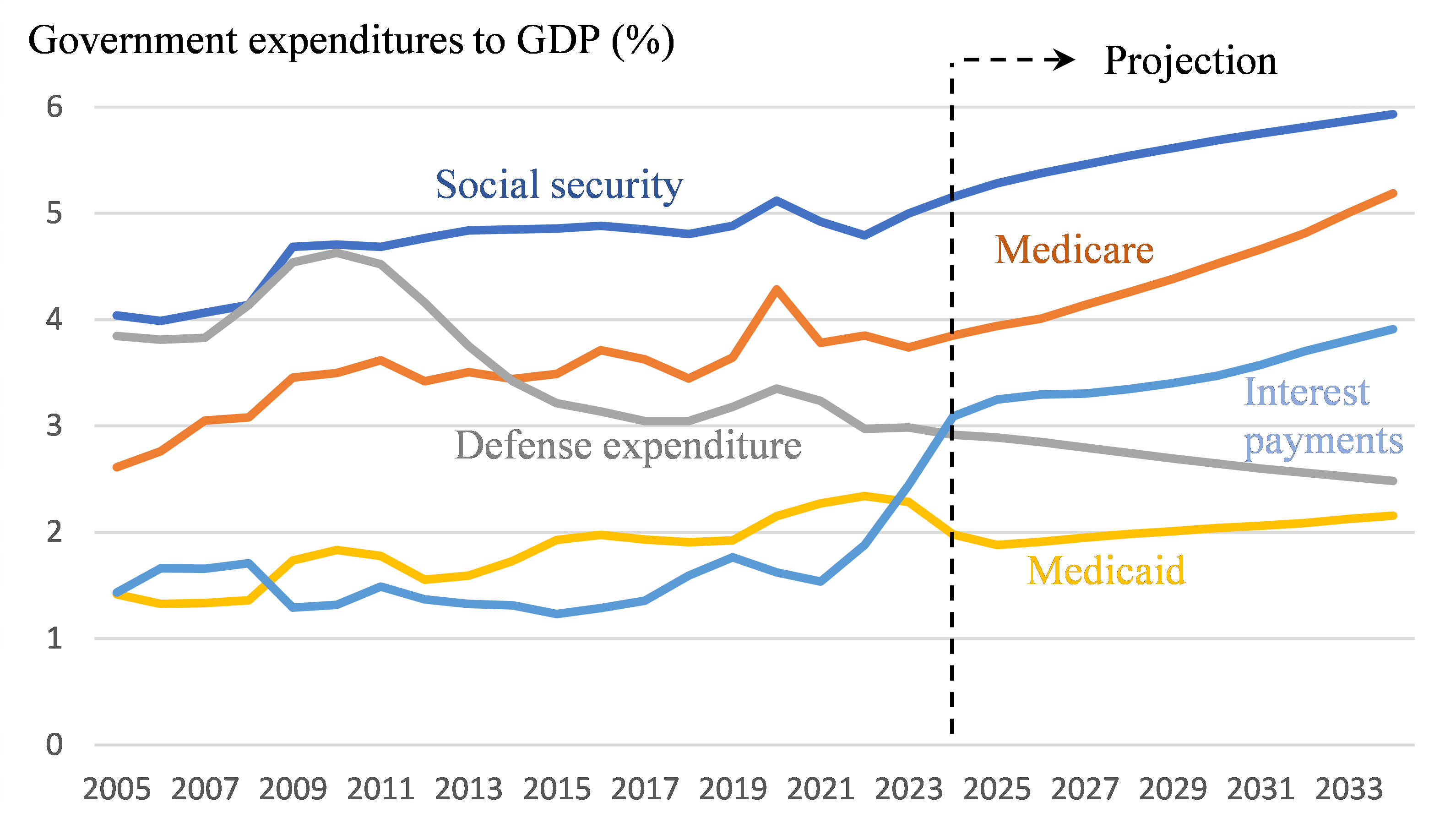

So how will this sharp rise in Treasury bond yields affect the U.S. government’s finances? The CBO provides fiscal projections for the U.S., and Chart 2 shows the future outlook for interest payments relative to GDP for each period over which the projections are compiled. As the graph clearly shows, interest payments have been revised upward in each updated projection, and in the most recent projections released in February 2024, interest payments are expected to reach $1.46 trillion (about ¥240 trillion) or 3.9% of GDP in 2034, even assuming future interest rate cuts by the Fed. Chart 3 shows the future outlook for each major expenditure item. Interest payments are expected to exceed defense expenditure in 2024, reaching $1 trillion (about ¥150 trillion) or 3.3% of GDP in 2026.

Chart 2 Future outlook for interest payments and the changes

Source: U.S. Congressional Budget Office

Chart 3 Future outlook for government expenditures

Source: U.S. Congressional Budget Office

Note: “Social security” includes non-medical benefits such as pensions and disability insurance.

Note: “Medicare” is a public medical insurance program for the elderly and disabled.

Note: “Medicaid” is a public medical insurance program for people with low incomes, etc.

Fiscal Management Issues

Then do these rising interest payments cause a concern over fiscal management? It depends on the factors behind the rise in interest rates. In terms of fiscal management, when the debt-to-GDP ratio remains at a stable level, there is no significant concern. The following can be used to describe the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Change in debt-to-GDP ratio

= (Interest rate - Growth rate) × Debt-to-GDP ratio in Previous period + Primary balance-to-GDP ratio

This equation shows that changes in the debt-to-GDP ratio can be broken down into three factors: (1) the difference between interest rates and growth rates, (2) the debt-to-GDP ratio in the previous period, and (3) the primary balance-to-GDP ratio. The factor related to interest payments is (1), but the key factor there is not the interest rate itself, but the difference between interest rates and growth rates. That is, if the current rise in interest rates is attributable to an increase in the natural rate of interest and entails an increase in the economic growth rate, it will not have a significant impact on fiscal management.

Nonetheless, a few aspects need to be discussed.

First, interest rates tend to rise moderately as debt-to-GDP ratios and budget deficits increase. Chart 4 summarizes representative empirical studies that have analyzed the impacts of outstanding debt and budget deficits on interest rates. Though there is some variation in the results of the analyses, most conclude that a 10 percentage point (hereinafter “ppt”) increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises interest rates by 0.3–0.4 ppt, and a 1 ppt increase in the budget deficit-to-GDP ratio raises interest rates by about 0.4 ppt. Before and after the pandemic, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio rose by about 20 ppt, from just under 80% to just under 100%. Applying this to the results of the above study, it can be interpreted that about 0.6–0.8% of the rise in interest rates is due to the buildup of outstanding debt. The 10-year Treasury rate was about 0.6–0.7% immediately after the onset of COVID-19 and is currently about 4%, a rise of more than 3 ppt over the period, of which we estimate that about one-fifth is due to higher debt balances. Moreover, the budget deficit has been on an upward trend in the post-Trump era and is expected to continue to swell in the coming years. If these trends continue, there is a possibility that ‘interest rate > growth rate’ will take hold.

Second, the debt-to-GDP ratio has increased following the COVID-19 pandemic. As discussed above, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio rose by approximately 20 ppt before and after the pandemic. As seen in the equation for the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio, (interest rate - growth rate) and the debt-to-GDP ratio in the previous period are multiplied together. This indicates that as the debt-to-GDP ratio increases, so will the effect of the difference between interest rates and growth rates on changes in the debt-to GDP-ratio. That is, when the debt-to-GDP ratio is high, its fiscal advantages are amplified when interest rates are below growth rates, while its fiscal disadvantages are also amplified when interest rates are above growth rates. Over the past decade, a decline in interest rates has provided more fiscal leeway for spending, but this can be reversed when interest rates are above the growth rate.

Third, in the wake of the pandemic, deficits in the primary balance are growing. Should ‘interest rate > growth rate’ take hold, the primary balance would have to improve in order to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. However, in the aftermath of the pandemic, and partly due to the impact of large-scale industrial policies, the primary balance deficit is increasing in the U.S. Judging by the political and electoral competition between the two major parties, the Democrats and the Republicans, it will not be easy to control the expanded public spending. The Biden administration has put in place major spending programs, including the Inflation Reduction Act, and if Trump returns to the presidency, it is anticipated that Trump will also render permanent tax cuts put in place during his first administration.

Chart 4 Summary of the impact of outstanding debt and budget deficits on interest rates

|

Research |

Subject |

Research outline |

Main conclusion |

|

Engen and Hubbard (2005) |

U.S. |

Examines the impact of a rise in outstanding debt on real interest rates using U.S. data |

|

|

Laubach (2009) |

U.S. |

Analyzes the impact of budget deficits and outstanding debt on interest rates by using U.S. data to identify how Treasury futures rates react to news about the Congressional Budget Office’s fiscal outlook |

|

|

Brook (2003) |

Developed countries |

Examines the impact of debt-to-GDP ratios and budget deficits on interest rates using data available worldwide |

|

|

Faini (2006) |

Eurozone |

Examines the impact of debt-to-GDP ratios and budget deficits on interest rates using data from the eurozone |

|

|

Kinosita (2006) |

19 OECD countries |

Analyzes the impact of debt-to-GDP ratios on interest rates using data from 19 OECD countries for the period 1971–2004 |

|

|

Kameda (2014) |

Japan |

Uses the economic stimulus package announced by the Prime Minister as a case study to analyze the impact of fiscal policy on interest rates |

|

|

Tanaka (2021) |

Developed countries |

Analyzes the determinants of nominal long-term interest rates using data from 1990 to 2019 for 25 developed countries |

|

|

Rachel and Summers (2019) |

Literature review |

Sorts out the impact of debt-to-GDP ratios on interest rates by using surveys of existing research |

|

The information above was prepared by the author.

Implications for Japan

At the time of writing this article, while the Bank of Japan raised its short-term interest rates from between -0.1% to zero to between zero and 0.1% and ended yield-curve control in March 2024, it is maintaining accommodative monetary policy. Since price increases in Japan are expected to be smaller than in the U.S., and any rate hikes are likely to be modest, so they are unlikely to lead to an immediate rise in government bond yields directly. Nevertheless, in light of trends in the U.S., the following issues should be considered and prepared for in advance.

First, existing empirical studies often find that a 10 ppt rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises interest rates by 0.3–0.4 ppt. Given the high level of Japan’s public debt to GDP ratio, there is a risk that an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio will add more to interest rates, in which case there is a concern that the interest rate would be above the growth rate.

Second, as discussed above, the difference between interest rates and growth rates affects the debt-to-GDP ratio by multiplying it by the debt-to-GDP ratio in the previous period. This means that a higher debt-to-GDP ratio creates a stronger tailwind for public finances when interest rates are lower than the growth rate, whereas it creates a stronger headwind when interest rates are higher than the growth rate. Thus, volatility increases with the difference between interest rates and growth rates.

The Japanese government expects to increase spending on defense, measures to cope with the declining birth rate, and other expenditures in the future. Taking into account the economic situation, the government needs to consider and prepare in advance for fiscal management with a view to the future.

(This article provides the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the views of the institution to which he belongs.)

References

Brook, A. M. (2003). Recent and prospective trends in real long-term interest rates

Engen, E. M., & Hubbard, R. G. (2004). Federal Government Debt and Interest Rates. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 19, 83–138.

Faini, R. (2006). Fiscal policy and interest rates in Europe. Economic policy, 21(47), 444-489.

Gale, W. G., & Orszag, P. R. (2003). The economic effects of long-term fiscal discipline. Urban Institute.

Kameda, K. (2014). Budget deficits, government debt, and long-term interest rates in Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 32, 105-124.

Kinoshita, N. (2006). Government Debt and Long-Term Interest Rates. IMF Working Papers, 2006(63).

Laubach, T. (2009). New evidence on the interest rate effects of budget deficits and debt. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(4), 858-885.

Rachel, Ł., & Summers, L. H. (2019). On secular stagnation in the industrialized world (No. w26198). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Tanaka, K. (2021). Why Do Interest Rates Remain Low Despite the Accumulation of Government Debt in Japan? , Financial Review, 2021(1), 4-33.