Tax specialist Shigeki Morinobu scrutinizes the international tax-avoidance schemes of US multinational firms and calls on Japan to join with Europe in efforts to update tax rules so that they better reflect modern realities and ensure fairness in corporate tax obligations.

* * *

Public criticism of tax avoidance by the global leaders of the digital economy has been escalating in the West in recent years, and measures to enforce closer links between the locus of value creation and that of tax payment have emerged as a topic of debate and deliberation in the Group of 7, the Group of 20, and other multilateral frameworks. Within Japan, however, the issue of tax avoidance by companies with worldwide value chains has received relatively little attention. In the following, I hope to shed light on this phenomenon and discuss its implications for the global economy.

The Low Tax Burden of US Companies

US digital powerhouses Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Netflix, Nvidia, and Tesla have a combined market capitalization of roughly $3 trillion, amounting to about 4% of the total value of all public firms worldwide. Admired as technological innovators and key drivers of global as well as US economic growth, these eight firms have distinguished themselves in another way as well―as international tax avoiders. Taking advantage of the highly dispersed global value chains made possible by today’s digital economy, they have used sophisticated and aggressive tax-planning techniques to minimize their tax liability on overseas earnings.

In Europe, the practices of US-based digital-economy businesses have come under growing fire over the past several years. In the United States, however, criticism of these tech companies has been fairly muted because their tax-avoidance schemes target income earned overseas, not domestically, and because they are powering US economic growth and creating American jobs.

Even within the United States, however, American firms are highly resourceful when it comes to reducing their tax bills, as suggested by their low effective corporate tax rateーthe percentage of reported pretax income paid in corporate tax (federal and state combined), on average. According to the 2011 report Cross-Country Comparisons of Corporate Income Taxes released by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the mean effective corporate tax rate of domestic US companies in the 2005-9 period was 19%. For Japanese companies, by comparison, the ETR was 33%, despite the fact that the average statutory rate for the same period was virtually the same (roughly 40%) in both countries. According to a survey by Citizens for Tax Justice, the top 288 US corporations had an effective federal tax rate of 19.4% between 2008 and 2012, when the corporate tax rate was 35%. Moreover, many of those top corporations paid no federal taxes whatsoever.

These figures testify to the ingenuity of big American companies when it comes to minimizing their tax liability. And with the rise of the global digital economy, US-based multinationals have discovered more and better ways to avoid taxes, particularly on income earned overseas. Let us begin by examining the case that set in motion current multilateral efforts to address tax avoidance in the digital economy.

Starbucks UK: A Template for Tax Avoidance

It was in 2012 that the international community began to get serious about developing comprehensive solutions to the problem of tax avoidance. The main catalyst for this shift was the public furor over revelations that Starbucks UK had paid almost nothing to the British government in taxes.

The uproar, which climaxed in anti-Starbucks public protests, began when it came to light that Starbucks UK had paid just £8.6 million in corporate taxes on about £3 billion in sales during its 14 years in existenceーan effective rate of 0.3%. It did this by using costly intragroup transactions to minimize income booked in Britain and maximize the revenue booked in low-tax countries.

For example, Starbucks UK purchased coffee beans at inflated prices from a Starbucks unit in Switzerland. This, of course, increased the Swiss unit’s pretax income, but in Switzerland profits tied to international trade in commodities like coffee are taxed at rates as low as 5%. The British unit also paid high royalties to a unit in the Netherlandsーa well-known tax havenーfor use of the Starbucks brand. In addition, it wrote off high interest payments on loans from the US unit. Together, transactions of this nature reduced the income reported by Starbucks UK to almost nothing.

Almost all developed countries, including Britain, have adopted “transfer pricing” agreements and regulations designed to prevent multinational companies from overpricing cross-border intragroup transactions in order to minimize their taxable income. If a company’s write-offs from such transfers are deemed to be out of line with charges on comparable “arm’s length” transactions between unaffiliated companies, tax authorities can adjust the accountingーand the tax billーaccordingly. After the Starbucks case called into question Britain’s transfer-pricing rules and their enforcement, the British government announced plans to crack down. In the meantime, however, Starbucks volunteered to pay some £10 million in taxes during 2013 and 2014 to quell the backlash, and the government settled for that without clarifying the legality of Starbucks’ transfer pricing.

Prime Minister David Cameron, galvanized by the public reaction, raised the issue of tax avoidance at several international forums in 2012. The G7 and G20 put the problem on their agendas and called for action by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. This led to the launch of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project, which I discuss in greater detail below.

The Starbucks UK case (though not involving an IT firm per se) is a classic example of recent trends in offshore tax avoidance, which occupies an ethical gray area between perfectly permissible tax reduction techniques and illegal tax evasion. If companies get too aggressive in their tax-planning strategies, tax authorities may challenge their accounting and force them to pay the difference. But owing to ambiguities and inconsistencies in tax rules and their enforcement, it is extremely difficult to predict whether any given scheme will be challenged. Reducing these ambiguities and inconsistencies through detailed, up-to-date international tax rules would benefit businesses and governments alike by enhancing predictability. This was one of the rationales for the BEPS Project.

The Problem with Tax Avoidance

Why should people in Japan or anywhere else be concerned about international tax avoidance by US multinationals?

First, it leads to unfair distribution of the tax burden and creates the perception that honesty does not pay. The wealthy have access to high-priced tax lawyers who can help them drastically reduce their tax bills, as the leaked Panama Papers and Paradise Papers attest; the same applies to big corporations. The knowledge that those with the highest incomes are avoiding their taxes makes everyone else resentful about meeting their own tax responsibilities.

Second, tax avoidance creates an uneven playing field for companies competing in the global economy. Through aggressive tax planning, US multinationals can boost their after-tax profits, gaining an advantage over other companies. For example, Amazon pays almost no tax on income from its sales to Japanese consumers, whereas Japan-based Rakuten, which follows the same basic business model, does. This puts Rakuten at an obvious disadvantage.

Third, tax avoidance deprives governments of badly needed revenues at a time of growing deficits. In the developed world, many governments are struggling to meet the costs of an aging society. Under the circumstances, sovereign states have a right and a duty to collect appropriate taxes on economic activity conducted in their countries. That means standing up to the US multinationals’ tax-avoidance schemes.

Finally, the profitability of international tax planning is fueling high demand for tax accountants and lawyers versed in such schemes, sucking talent into an industry that contributes nothing of value to society. Ethical questions aside, it is a waste and a loss to the nation when its brightest accountants and lawyers, attracted by high salaries, devote their talents to helping companies avoid the taxes needed to pay for social security and other vital services.

Amazon in Japan: No Permanent Establishment?

Next, let us look at Amazon.com as an example of international tax avoidance by a giant e-commerce firm.

Today Amazon surpasses all other e-commerce businesses in sales to Japanese consumers. Its wholly owned Japanese subsidiary, Amazon Japan G.K. (a limited liability company), operates massive “fulfillment centers” (warehouses) in Chiba Prefecture and elsewhere.

Foreign-based companies doing business in Japan are subject to Japan’s corporate tax only if they maintain a permanent establishment (PE) here. Amazon’s facilities in Japan are basically warehouses, and under international tax agreements, warehouses have been excluded from the definition of a PE on the basis of their “preparatory or auxiliary character.” Consequently, (US-based) Amazon has not been subject to Japan’s corporate tax. Amazon Japan G.K., on the other hand, is a Japanese-based corporation, and as such is clearly subject to the country’s corporate income tax. However, under Amazon’s “commissionaire” distribution contract with its Japanese subsidiary, commissions just barely cover costs, so there is virtually no business income to tax.

In 2009, the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau assessed taxes on Amazon’s Japan-derived income, claiming that Amazon’s business in Japan should be regarded as having a permanent establishment. The dispute was referred to higher authorities in Japan and the United States, and while the results of those talks have not been made public, it seems clear that Japan was unable to prevail and that Amazon’s business remains fundamentally exempt from the Japanese corporate tax.

Amazon would doubtless argue that warehousing is an inherently low-risk, low-value-added business that does not generate substantial profits; the real source of Amazon’s earnings is its e-commerce business model, in which transactions are conducted over the Internet. What this suggests is that, from the standpoint of the digital economy, the PE concept itself is outdated. The rule that a business is subject to taxation only if it maintains a physical establishment made sense in an era in which such a presence was necessary to conduct cross-border retail transactions on a large scale. But the Internet has made it easy to conduct and settle transactions without a PE. In some cases, all one needs on the ground is a few local employees for support and PR purposes.

Japan is not the only victim. France, Germany, and other countries in the European Union have grappled with tax avoidance by e-commerce companies and other digital-economy enterprises and concluded that current international rules are inadequate to address the problem. This is why the BEPS Project took up the problem of tax avoidance in the digital economy as a common challenge facing the developed world.

Following recommendations in the 2015 BEPS Project report, the OECD’s latest guidance regarding PEs describes the structure used by Amazon in Japan and concludes that, since “the business activities carried on . . . at the warehouse and at the office constitute complementary functions that are part of a cohesive business operation,” the company may be seen as having a permanent establishment in the jurisdiction in question. However, an OECD directive alone cannot alter Amazon’s tax status in Japan. For that to happen, Japan must persuade the United States to amend the bilateral tax agreement accordingly, and that will not be easy.

Google: Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich

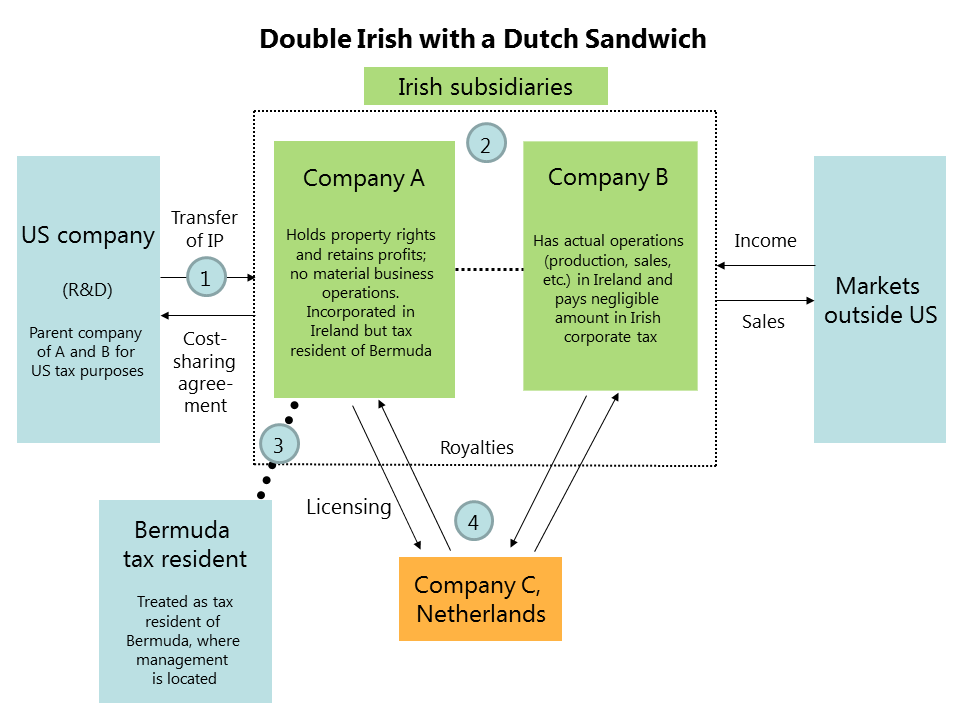

Another classic international tax avoidance scheme is the “double Irish with a Dutch sandwich” arrangement made famous by Google and Apple. Let us take a look at Google’s use of this ingenious structure with the aid of the figure below.

To begin with, the US parent company establishes two Irish subsidiaries, companies A and B. It transfers its intellectual property rights to A, a shell company with no substantive business operations (see interface 1 in accompanying figure). The parent company minimizes its financial gains from the transaction by entering into a cost-sharing agreement with A.

The other Irish subsidiary, company B, is a real business that uses the intellectual property rights transferred to A to create content for sale outside the United States. It has actual operations that employ a large number of people locally. It minimizes its corporate tax liability in Ireland by writing off the high royalties it pays for those rights.

The scheme also takes advantage of check-the-box rules, a feature of the US corporate tax code that allows eligible business entities to elect their own classification for federal tax purposes. Company B elects to be treated as a branch of company A. This means that, for US tax purposes, B, which has actual production and sales operations, is part of A (2). In so doing, A is shielded from US tax rules targeting shell companies in offshore tax havens.

Furthermore, company A, while incorporated in Ireland, holds its shareholder and board meetings in Bermuda, and is thus able to claim status as a tax resident of Bermuda under Ireland’s “central management and control” test for tax residence (3). (In most developed countries, including Japan, tax residence is determined by place of incorporation.)

However, under Irish tax rules, royalty payments to companies headquartered outside the EU are subject to withholding tax. To avoid those taxes, company A routes the royalties through a subsidiary (company C) incorporated in the Netherlands, which does not subject such transfers to withholding tax (4). The royalties paid by company B to reduce its Irish tax liability are booked in Bermuda, where they escape taxation entirely. Through strategic “treaty shopping” and the shifting of intangible assets and their profits, Google has drastically reduced its tax liability on corporate profits earned outside the United States. Similar schemes have been employed by such platform businesses as Uber and Airbnb.

Two closely interrelated factors have facilitated tax-avoidance schemes of this sort: the rise of the digital economy and the growing emphasis on intangible assets. In the following, we will take a closer look at the impact of these developments.

Challenges of the Digital Economy

This century has seen the meteoric rise of e-commerce, as well as such innovative models as cloud computing, platform businesses, and more. These new developments are all part and parcel of the digital economy, which continues to grow and develop at a breathtaking rate. How has this affected the ability of governments to assess and collect taxes?

To begin with, the digital economy has greatly accelerated the shift toward intangible assets. Increasingly, such intangibles as patents, copyrights, and trademarks form the core of companies’ corporate value, especially in the IT field. From a taxation standpoint, valuation of such assets can be very difficult. In some cases, an asset that had little value at the time it was sold ends up generating more profit than anyone anticipated. The challenge becomes even more complex when we consider the formation of intangible assets through the collection, analysis, and utilization of “big data.”

While valuing intangible assets is difficult, moving them is extraordinarily simple in our day and age; unlike tangible assets, they can be transferred halfway around the world with a single mouse click. Digitalization makes it easy for companies to shift their own intangible assetsーalong with the accruing profitsーfrom the countries where value is actually created to jurisdictions with more advantageous tax systems.

As an example, the US-based ride-hailing service Uber formed a business entity in the Netherlands called Uber International C.V., to which it transferred the parent company’s intangible assets. Then it established another Dutch subsidiary called Uber B.V., which collects all the payments received from Uber drivers anywhere outside of the United States, while paying royalties to Uber International C.V. (for the use of Uber’s intangible assets).

Second, the Internet has given companies themselves unprecedented mobility, allowing them to operate with a borderless mindset and conduct huge volumes of business without setting up permanent physical establishments. Yet our international taxation regulations and agreements are predicated on geographical, political, and physical constraints that no longer apply. This mismatch has severely compromised the ability of governments to tax the income of multinational corporations. Amazon, as we have seen, has taken advantage of international agreements excluding warehouses from the definition of a PE to avoid taxation in countries where it does a thriving business. Moreover, platform businesses like Airbnb require no physical presence whatsoever to do a profitable business in a country. The traditional concept of the PE is no longer a valid test for determining tax jurisdiction.

The digital economy also poses challenges for the collection of consumption or value-added tax. Cross-border sales of digital products, from music and video to advertising services, have exploded in recent years, and current consumption-tax systems cannot keep up with the activity. In this context, there is a need for special mechanisms to tax business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions, as distinguished from business-to-business (B2B) transactions.

The BEPS Project’s Unfulfilled Promise

As mentioned above, the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project was launched in 2012 amid a growing awareness that existing international tax rules were inadequate to cope with the realities of the new global economy. Tax experts representing both OECD and non-OECD G20 countries came together to create “a single set of consensus-based international tax rules to protect tax bases while offering increased certainty and predictability to taxpayers.” They set out to forge concrete agreements on 15 actions to “equip governments with domestic and international instruments to address tax avoidance, ensuring that profits are taxed where economic activities generating the profits are performed and where value is created.”

In 2015, after two years of deliberation, the BEPS Project issued a set of “final reports” on the 15 action items. The OECD’s Task Force on the Digital Economy (TFDE) prepared the report on Action 1, “addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy,” which addresses both direct taxation (corporate income tax) and indirect taxation (consumption taxes, including VAT). Unfortunately, the report produced little in the way of substantive measures for addressing the fundamental problems we have examined above.

With respect to corporate income taxes, the PE concept was a major bone of contention in the deliberations. Some felt strongly that the PE principle had outlived its usefulness and needed to be replaced by an alternative criterion or mechanism adapted to the digital economy. But while several possible alternatives were discussed, none were recommended in the 2015 report. Instead, the report called for modification and elaboration of existing rules, including stricter limitation of exceptions to PE status, while the task force continues to work on the problem.

With regard to consumption taxes on cross-border digital transactions, the report basically recommended that countries apply the principles of the OECD’s International VAT/GST Guidelines. For B2B, this generally means identifying the tax jurisdiction by the location of the customer and using “reverse charge” methods to collect. For cross-border B2C services, the report stressed the merits of a destination-based system in which each transaction is taxed in the jurisdiction in which the consumer is resident, with collection enforced through the registration of non-resident suppliers. (Japan incorporated these recommendations in its 2015 revision of the Consumption Tax Act).

Finally, the TFDE pledged to continue work on the issues and monitor developments over time. An interim report on that work is scheduled for 2018, and a final report for 2020.

The lack of progress on a new regime to address the challenges of the digital economy is not entirely surprising, given the complexity of the problem and the fact that not all governments involved in the project are equally motivated to change the status quo. It will not be easy reaching a consensus on a replacement for the PE principle, which has functioned as a mainstay of international tax agreements for many years. Until then, efforts must focus on rigorous implementation of other action items, particularly “preventing artificial avoidance of permanent establishment status” (Action 7).

Beyond BEPS

As a basis for ongoing deliberation, the 2015 report set forth the following three options as possible alternatives to the PE principle.

The first option is the adoption of a new “nexus” test based on the concept of “significant economic presence.” Under this option, an enterprise that generated a certain level of revenues from customers in a given country could be deemed to have a taxable presence in that country on the basis of its digital presence, as gauged by such factors as domain name and data collected from visitors and customers.

The second option is to impose a withholding tax on certain types of e-commerce transactions.

The third alternative is to institute an equalization levy, a new type of tax on digital transactions designed to equalize the tax burden on remote and domestic suppliers of similar goods and services.

Exactly how these novel mechanisms would be designed and implemented remains unclear. It will be the job of the project team to flesh out the details in the 2018 interim report and the 2020 final report.

Meanwhile, the EU has begun deliberations of its own in hopes of accelerating progress. A key impetus for the launch of these talks was Britain’s decision to adopt a diverted profits tax without waiting for the final conclusions of the TFDE. A fragmented and incoherent response by individual countries could easily lead to inconsistencies and inequities in international taxation, including double taxation. Anxious to avoid such problems, the European Commission began talks in hopes of expediting a general agreement.

According to a press release issued by the EU Economic and Financial Affairs Council last October, the digital taxation agenda will consider both short-term “quick fixes” to fill gaps in international tax rules and a more long-term comprehensive approach.

Options under consideration for “quick fixes” include an online advertisement tax, a withholding tax, and an equalization tax to address the problem of nontaxation of transactions involving online content, such as Internet advertising and video streaming. These are short-term expedients that rely on the existing VAT system or the adoption of a new sales tax, and the details have yet to be hammered out.

Comprehensive solutions, by contrast, focus on developing international rules and mechanisms to ensure the fair taxation of corporate income. A key proposal would expand the definition of PE to include a significant digital presence in a given jurisdiction. At the same time, there is a need for workable methods of calculating the taxable income attributable to such a PE. Ultimately, those deliberations may extend to the concept of formulary apportionment, the use of an agreed formula to allocate the profits of a given multinational corporation or group among the jurisdictions where it has a taxable presence.

At present, the EU’s stated objective is to provide the basis for a broader agreement by the OECD in hopes of achieving a global solution. However, it has made clear that it is prepared to act on its own if the TFDE’s 2018 interim report does not show adequate signs of progress.

In my view, the idea of using “significant digital presence” as a basis for taxation has merit. Since many businesses in the digital economy can conduct their operations without a permanent physical presence, the traditional PE concept is no longer a viable basis for determining tax status and jurisdiction. We clearly need a more appropriate standard, and it seems to me that the size of “customer data” can provide measurable criteria. This would also fall into line with the idea of shifting the focus of corporate tax from income to cash flow.

It is also important to recognize that the digital economy comprises a variety of business models, each presenting its own tax challenges. Amazon is fundamentally an online retailer. Google earns most of its revenue from online advertising. Uber is a platform business that matches users to providers in the sharing economy. We need to find a set of common rules that take into account the specific features of all these business models.

The exploitation of big data has been cited as a key to business success in the digital economyーhence the buzzword “data economy.” Increasingly, businesses rely on massive amounts of data collected by digital services to generate value from intangible assets, such as patents, trademarks, and business models. How do we assess the value of this data for tax purposes and allocate it among tax jurisdictions? This question is likely to dominate discussions of international tax policy in the post-BEPS era.

Moving at the Domestic Level

Japan shares many of the concerns driving the EU’s current digital taxation agenda. In Japan as in Europe, US-based digital-economy companies have racked up profits while avoiding taxation on that income. Japan needs to keep abreast of the EU’s findings and work with the OECD to prevent such tax avoidance.

Following through on an election promise, the cabinet of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently approved a ¥2 trillion package to support childcare services and free education. Having long complained about the disproportionate emphasis on the elderly in Japan’s social spending, I heartily applaud these signs that the government is finally beginning to address Japan’s long-term growth challenges. Expanded daycare is essential to boost the nation’s low birthrate, and investment in early childhood and higher education is needed to reduce economic inequality and lay the foundation for future growth.

That said, the ¥1.7 trillion to be allocated to this program from a scheduled consumption tax increase was already earmarked for the government’s deficit reduction plan. The government will need to make up the difference through a combination of spending cuts and increased revenues from other taxes. In terms of spending, the key is healthcare reform, including the application of new information technology and the systematic promotion of evidence-based treatment. To boost tax revenues, the government will need to work assiduously on several fronts, including higher taxes on the wealthy and reduced exemptions for individuals receiving both pension benefits and employment income.

Under the circumstances, every effort should be made to ensure that companies like Amazon and Google pay their fair share as well. Cognizant of the EU’s progress on its agenda, we should work with the OECD to hammer out more detailed transfer-pricing rules to prevent base erosion and profit shifting through the transfer of intangibles.

Where questions of tax jurisdiction are concerned, Japan is just now gearing up to revise its tax code in accordance with the latest OECD guidelines on the types of facilities that can be treated as permanent establishments. However, the EU has already gone far beyond such measures. In August 2016, the European Commission ordered the Irish government to recover as much as 13 billion euros in back taxes from Apple, ruling that Ireland’s tax breaks amounted to illegal state aid. Even the business-friendly administration of US President Donald Trump has been eyeing the profits retained by US IT firms in offshore tax havens as a way to finance some of its tax cuts.

Anticipating widespread unemployment accompanying the development of artificial intelligence, some have suggested that every citizen be entitled to government subsidies guaranteeing a basic income. Before we can contemplate such an expansion of entitlements, we need to talk about ways of financing our current obligations in a sustainable manner. To control the deficit, the Japanese government unquestionably needs to rein in social spending with an emphasis on healthcare costs. But such efforts should be accompanied by revenue-raising measures targeting those who can and should contribute more, including American IT firms.