- Article

- Tax & Social Security Reform

Toward a Unified Approach to Fair Taxation of the Digital Economy

January 28, 2020

An international consensus on new tax rules for the digital economy is gradually taking shape. Tax expert Shigeki Morinobu sums up the latest OECD recommendations on nexus and profit allocation and their implications for government and business.

* * *

Some 130 countries around the world are working together to address the challenges of tax avoidance and tax-base erosion in the digital economy with the institutional support of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Group of 20. Arriving at a consensus solution has proved a daunting task, but in recent months, progress has accelerated, as the United States has accepted the need for substantive rule changes. In October and November 2019, the OECD Secretariat released two proposals with a view to securing a basic agreement by the end of January 2020 and publishing the details of a consensus solution by the end of the year.

The Secretariat’s proposals address the two previously agreed-on “pillars” of a comprehensive agreement. Pillar One targets profit-allocation and nexus rules with a view to expanding the taxing rights (tax base) of market countries. Pillar Two takes aim at tax havens through rules that would give jurisdictions the right to “tax back” profits that have escaped a minimum effective tax rate. My focus here is on the former, the OECD’s Proposal for a “Unified Approach” under Pillar One. In the following, I hope to shed light on the purpose, scope, and impact of the rules currently envisioned, as well as key issues to be clarified in the months ahead.

The Basics of Pillar One

In today’s digital economy, businesses can rake in vast profits from sales in countries where they have no physical presence. Yet current international rules permit a country to tax the revenues of a non-resident business only if the business has a permanent (physical) establishment in that country. Departing from this long-standing rule, the OECD Secretariat’s Pillar One proposal would grant “new taxing rights” to the user or market countries where profits are actually generated, independent of physical presence.

In terms of scope, the OECD’s approach “covers highly digital business models but goes wider—broadly focusing on consumer-facing businesses” above a certain sales threshold. In this way, it accommodates the US-proposed “marketing intangibles” approach, which targets profits from firms’ intangible assets, including brand value, instead of focusing narrowly on digital businesses per se. The scope of “consumer-facing businesses” requires further clarification, but it is assumed to exclude such sectors as extractive industries and commodities.

With respect to tax nexus, the proposal calls for the adoption of new rules based largely on sales (while also taking into account such factors as the size of each market country’s economy) without regard to physical presence. Although the new nexus rules would most strongly impact businesses that rely on remote sales, they would apply also to multinational companies that sell products via local subsidiaries, thus maintaining some degree of business-model neutrality.

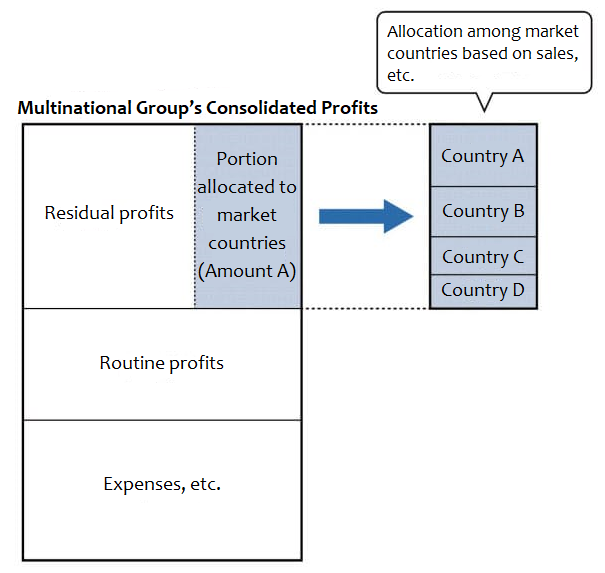

In regard to profit allocation, the proposal suggests a three-tiered mechanism to enhance simplicity, certainty, and stability in the tax system while preventing double taxation. The pivotal element in the plan is Amount A, the portion of a corporate group’s profits allocated to market countries. Amount A is a certain share of the group’s “deemed residual profits” —that is, everything beyond an agreed “routine” profit margin. Amount A would be allocated among the eligible market jurisdictions primarily on the basis of sales.

Proposed System for Allocation of Profits (Amount A)

Ironing Out the Details

Many important details of the new rules remain to be ironed out, including the revenue threshold for application of the new rules, the definition of routine and residual profits, and the share of profits to be allocated to the eligible market jurisdictions (Amount A).

The proposal that currently enjoys the most support would apply the new profit-allocation rules to multinational corporate groups involved in consumer-facing businesses and earning 750 million euros (roughly ¥90 billion) or more in consolidated sales (all overseas subsidiaries included), and it would designate all profits in excess of 10% as residual profits. However, in the case of corporate groups involved in business-facing as well as consumer-facing operations, it remains unclear whether the 10% threshold would apply to the group’s overall profits or just the profits from its consumer-facing businesses. With regard to the portion of deemed residual profits to be allocated to eligible market countries as new taxing rights, the current climate of opinion seems to favor a 20% share.

Thus, in the case of a large corporate group with a 25% profit margin, 15% of annual sales would be considered residual profit, and 20% of that, or 3% of sales, would be allocated among the market countries as taxable business income.

Perhaps the biggest unresolved issue is the scope of “consumer-facing businesses, broadly defined.” The OECD proposal suggests that the category might include certain digital business-to-business models, such as online advertising services and marketplaces. This is a point that needs to be clarified as soon as possible.

The impact of the new rules on a given country’s tax revenues will depend on the relationship between revenues generated and profits booked in that country. Countries like Ireland and Singapore that have focused on attracting investment through low corporate tax rates will generally see a drop in tax revenues, while most other countries will experience an increase.

In Japan, there are close to 200 listed companies reporting sales in excess of ¥90 billion and an operating margin over 10%. However, since Amount A is based on a group’s worldwide earnings, including profits booked to overseas subsidiaries or regional headquarters (a common tax dodge among big tech firms), the new rules need not result in a net shift of taxable profits away from Japan.

When considering the consequences for individual Japanese businesses, we need to take Pillar Two into consideration as well. Rules recommended under the OECD’s Global Anti–Base Erosion Proposal would hit multinationals that engage in aggressive tax planning, such as the shifting of profits to subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions. Companies that have been straightforward in their tax accounting are unlikely to see any substantial change in their tax bill.

Staying the Course

The recent progress toward an agreement on digital taxation reflects a change in attitude on the part of the United States, which had previously resisted any substantive reform targeting multinational tech giants.

What precipitated the change in attitude was alarm over unilateral action by countries like Britain and France. The proliferation of various digital taxes at the national level would vastly complicate matters for digital businesses to the detriment of the global economy and render meaningless the years of work tax authorities have put into the establishment of consistent international rules. Any G20/OECD agreement must entail abolition of these unilateral taxes. In addition, the final agreement must provide for a collection mechanism that not only eliminates double taxation but also minimizes complexity in consideration of the costs of administration and compliance.

The G20/OECD initiative was undertaken on the premise that the current international rules of taxation are out of step with our rapidly developing digital economy. The gap has allowed certain multinational corporations, particularly US-based tech firms, to avoid paying taxes in the countries where their profits are generated, in some cases by booking intangible assets and profits in tax havens and low-tax countries. This is problematical because it deprives governments of much-needed tax revenue and gives tax-avoiding multinationals an unfair advantage over conventional businesses and domestic competitors.

The OECD proposals, while admittedly slanted toward the American approach rather than the earlier British proposal, address these core concerns. Japan is to be commended for its role in facilitating agreement during its tenure as G20 president, while at the same time lobbying to minimize the impact on its manufacturing industries.

Translated by the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research from "Shohichikoku ni shinkazeiken haibun," Keizai Kyoshitsu, Nihon Keizai Shimbun, December 6, 2019.