O-2022-033

Rapid economic growth in the first decade of this century saw China supplant Japan as the world’s second largest economy, but more recently, China’s growth has plateaued as population decline pushes up labor costs and makes exports less competitive. Rather than putting its faith in free-market economics, however, the Xi government is attempting to revert to a planned economy. (The article is reprinted from Nippon.com.)

A Japan Model for the Rest of East Asia

You only need look at the development trajectories of East Asian nations to see that Japan’s spectacular economic success after World War II was a source of significant hope for the other countries in the region. The “flying geese model,” first described by Hitotsubashi University’s Akamatsu Kaname in 1935 to explain the process of Japanese-modelled economic development, provided inspiration to the other countries in the region.

The rapid growth of the Japanese economy after World War II was the result of not only market mechanisms but also government initiatives to foster key industries through economic and industrial policy. In the 1980s, the phrase “Japan as number one” was coined, and the United States, despite being a military ally, came to see Japan as a threat and imposed sanctions on Japan’s automotive, appliance, and other export industries, creating trade friction.

Following Japan’s example, the other nations in East Asia raced to grow their own major industries, especially in and after the 1980s, when the other countries in the region achieved miraculous economic growth by rolling out electrical, highway, railway, and other infrastructure. To use the terms of reference of the flying geese model, Japan led the flock, followed by the emerging newly industrialized economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, and then the Southeast Asian members of ASEAN. Coming up from the rear of the formation was China, which was reforming its economy and beginning to open up.

While East Asia’s economic development appeared to be going swimmingly, 1997 brought an overnight setback in the form of the Asian financial crisis. Paul Krugman summed up the crisis by arguing that East Asia’s economic growth was an illusion because it focused purely on investment and was not accompanied by any improvement in productivity. While Krugman, a proponent of a productivity-oriented theory of economics, would go on to receive the Nobel Prize for economics, his assessment of the crisis was completely off, because beginning in 1999, the East Asian economies all underwent a V-shaped rebound.

“Low Human Rights Advantage” Behind China’s Growth

In 2001, China got its long-held wish to join the World Trade Organization. China’s WTO membership was conditional on the complete opening up of domestic markets, a change that led predominantly international corporations to increasingly consolidate their factories and supply chains in China. In the process, China acquired business expertise and state-of-the-art technology from foreign corporations, becoming the “factory of the world.” An examination of China’s economic development shows that the country was able to grow by combining strategies it learned from Japan with its own ideas. Specifically, China is a population superpower, and for the export and manufacturing industries, an endless supply of labor is essential in order to mass-produce cheap products.

Forty years ago, most of China’s cheap labor took the form of workers from agricultural communities. While the Chinese government does not officially allow peasant farmers to migrate to cities, it did begin allowing these farmers to work in cities unofficially—unofficial in that peasant farmers that migrate to urban areas to work cannot register as residents. These “peasant workers” are not entitled to health insurance, pensions, or compensation for work-related injuries. This setup enables capitalists to save on such expenses. Tsinghua University historian Qin Hui calls this China’s “low human rights advantage,” a description which is in a way fair: based on the conditions in which these workers work and live, it is no exaggeration to call them “slaves.” Such were the circumstances that enabled the Chinese economy to take off.

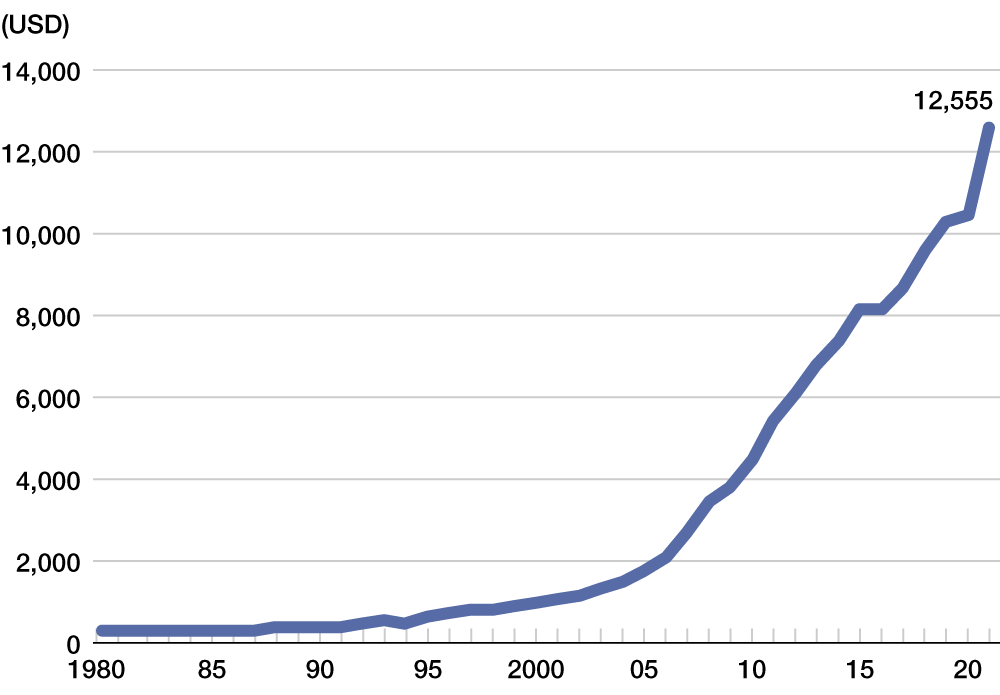

Figure 1. Chinese Per Capita GDP

Created by Nippon.com based on data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Figure 1 shows China’s gross domestic product per capita. While this graph is in US dollars and therefore influenced by exchange rates, it shows how the Chinese economy really took off in the 2000s, growing most rapidly between 2000 and 2010.

The impact of China’s joining of the WTO on direct foreign investment was not only quantitative but qualitative. In addition to building factories that took advantage of China’s cheap labor, foreign investors consolidated entire supply chains in China, as well as establishing a great number of research and development centers. China had in every sense become the “factory of the world.”

Cheap Labor a Thing of the Past

The problem is that since 2001, the Chinese economy has been steadily changing. In China, it is foreign corporations that lead the country’s high-tech industries. None of the world’s top 10 semiconductor manufacturers is Chinese, and while some 26 million vehicles were sold in China in 2021, the manufacturers of the cars considered most desirable by Chinese drivers are all based overseas. Despite these issues, however, the Chinese economy was still able to combine cheap labor and foreign capital to become the world’s second-largest economy.

The problem is what to do now. Firstly, 40 years of the one-child policy has caused China’s birthrate to fall so far that the working-age population has already begun to decline, and China’s total population is also projected to start falling sooner or later. In other words, the “population bonus” that gave China its advantage in the past is rapidly disappearing. While at one time, growth was supported by the movement of workers from relatively unproductive agricultural industries into the more productive mining, manufacturing, and service industries, this dynamic is rapidly disappearing due to the fall in the birthrate and the decline of the working-age population. This is known as the “Lewis turning point.”

Secondly, the recent reorganization of the world’s supply chains has made it likely that overseas corporations will move some of their factories from China to other emerging economies. Once China’s supply of labor begins to fall, labor costs will increase, and low-added-value industries will move to emerging nations where labor costs are lower. In their place will come a more advanced industrial profile. This is exactly what is supposed to happen under the flying geese model.

Markets Still Not Open Enough

The question, though, is whether China will be able to progress to the next stage now that its development model has achieved such spectacular success—that is, to transition from a developing nation to an industrialized economy. In academia, too, there is much interest in the question of when China’s nominal US-dollar denominated GDP will overtake that of the United States. At present, however, China’s economic growth—in particular, growth in high-value-added industries—is driven by foreign capital. If China’s government is unable to boost the technical abilities of its local industries, China will never successfully industrialize. Granted, in terms of per-capita GDP, China has already joined the ranks of the middle-income countries. However, a closer look at reveals that China is in fact falling into what is known as the “middle income trap,” making it unable to change its development model or strategy to move on to the next phase of more advanced economic growth.

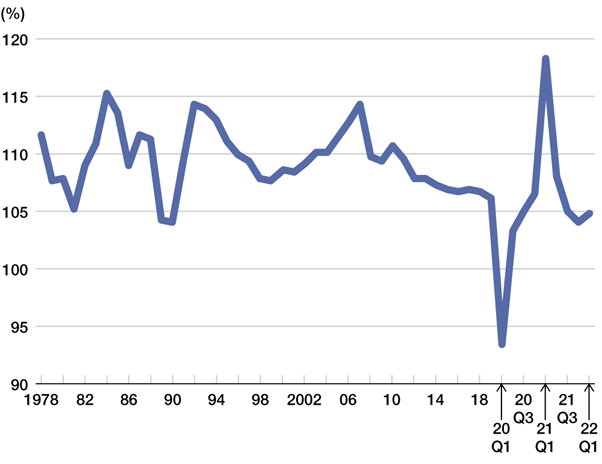

Figure 2. Real GDP Year-on-Year Growth in China

Created by Nippon.com based on data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Figure 2 shows that China’s economic growth rate has been trending downward since 2010. While the Chinese economy was exposed to volatility during the COVID-19 pandemic, the underlying slowing of the economy has not changed. In March 2013, as Xi Jinping assumed power, the National People’s Congress indicated that it was prepared to accept the slowing of the economy, which at the time was referred to with the buzzword xin chang tai (“new normal”). In other words, moderate growth was the new reality, and there was no longer any need to obsessively pursue rapid growth. However, China’s economic slowdown has continued unabated.

One may recall that when China joined the WTO in 2001, the Chinese government promised to open up all of its domestic markets, including its financial markets. However, the current state of affairs makes it evident that China has not gone far enough in opening its markets, and this is what sparked the trade war with the United States. At issue in this trade standoff is the question of whether China should comply with the existing set of international rules. The Chinese government counters that the current rules were drawn up by industrialized nations, and are often unfair to developing countries. In this context, China has become adversarial toward industrialized economies, and increasingly isolated in international society.

Reverting to a Planned Economy

China’s domestic situation, meanwhile, shows an increasingly pronounced trend of reversion to a planned economy. The last 40 years of economic growth are the product of economic liberalization, but since Xi took over as leader, the government has tried to make state enterprises larger and more powerful. This has resulted in increasing pressure on tech companies like Alibaba and Tencent. If China had been able to achieve the same kind of growth under a system led by state enterprises, there would have been no need for it to carry out reforms 40 years ago to open up its economy. Why, then, is the Chinese government now trying to increase its control over the economy? Why, rather than making the economy freer, is the Chinese government leaning toward an economic policy characterized by state-owned enterprises?

The only rational explanation is that excessive economic liberalization runs afoul of the Chinese Communist Party’s rule, so the party has decided to impose more controls. The issue is that by imposing excessive controls on the economy, it could threaten its own control over the country. In other words, if the Chinese economy stops growing, the party’s power will automatically decline. It is indeed a dilemma.

To sum up, in the short term, the failure of China’s Zero-COVID policy, the Ukraine crisis, and the China-US conflict could further slow the Chinese economy. At the same time, China also faces longer-term issues in that its declining birth rate and falling working-age population will cause it to fall into the “middle income trap.” The trend for foreign corporations to move their supply chains out of China is also hampering efforts to shift to a more advanced industrial profile. Under the circumstances, the rapid economic slowdown is a moment of truth for the Xi government, which is attempting to increase its control over the economy. Xi aims to be re-elected for a third term at the Communist Party National Congress later this year, but faces considerable headwinds.