- Article

- Tax & Social Security Reform

Is Working Good for Our Seniors? Mulling a Change in Japan’s Retirement Age

January 28, 2021

Despite widespread agreement on the need for pension reform in Japan’s super-aged society, the idea of raising the statutory retirement age remains a political third rail. Takashi Oshio hopes to kick-start the conversation with a statistical estimate of the health and employment effects to be anticipated from raising the pension age to 70.

* * *

In 2019, the Japanese government announced a new policy initiative aimed at “reforming social security to benefit all generations.” Achieving such a reform in a fiscally sustainable manner will necessarily involve boosting the ratio of active contributors (workers paying into the system) to beneficiaries (retirees drawing public pension benefits). But Japan’s political leaders are afraid to propose the obvious step of raising the statutory retirement age. In the following, I present a case for raising the pensionable age to 70, backed by a preliminary estimate of the effects on employment and health.

The Need for More Contributors

As Japanese society has aged, the ratio of beneficiaries to contributors has soared, putting an unsustainable strain on workers and the system as a whole. The quickest and most effective way to relieve that strain is to convert beneficiaries into contributors.

With this understanding, Japanese policymakers have emphasized a number of steps aimed at keeping seniors in the labor force. These include requiring companies to give their regular employees the option of working until they reach the age of 70 (as by raising the mandatory retirement age or rehiring retirees), extending the system of delayed retirement credits past the age of 70, and encouraging nontraditional work styles.

Conspicuously absent from their proposals, however, is the most obvious and effective means of keeping more seniors in the labor force: raising the age at which one can begin receiving pension benefits. The pensionable age under the National Pension scheme is currently 65. That for the Employees’ Pension Insurance scheme, which is rising incrementally, will reach 65 in 2025. At present, no further change is envisioned.

Developed countries around the world are facing the need for pension reforms to ensure fiscal sustainability and intergenerational fairness. But raising the pensionable age is a political hot potato, and Japanese politicians are no more eager to touch it than anyone else. Moreover, the Japanese government has preemptively shut down the debate by asserting that raising the statutory pension age would do nothing for the fiscal health of the pension system, given the existence of the “macroeconomic slide” mechanism, which automatically adjusts benefits in response to inflation and demographic trends.

Even if that is the case, all things being equal, would it not be preferable to limit future cuts in benefits if possible? If raising the pensionable age would increase the number of “contributors” relative to beneficiaries—a major goal of reform—it seems a shame to exclude that option from consideration.

Modeling the Relationship Between Employment and Health

One possible argument against raising the pensionable age would be the impact of continued employment on health. Recent reports of a jump in workers’ compensation claims among the elderly have raised concerns. If keeping people in the labor force beyond a certain age results in more health problems and more healthcare spending, then no one benefits. On the other hand, some research suggests that delaying retirement can have a positive effect on health. Moreover, the causal relationship between employment and health is bidirectional, that is, healthier individuals are more apt to keep working.

Bearing this complexity in mind, I undertook a rough calculation of the changes in employment and health outcomes that might be expected if we raised the pensionable age to 70. To begin with, I applied regression analysis to 1986–2016 health and employment data from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. Using the instrumental-variables method to control for the effect of health on employment, I was able to separate out the effect of pensionable age on health and model the relationship statistically.

With that model and the MHLW’s data from 2016, I carried out a simulation to estimate how raising the pensionable age to 70 would affect health outcomes and employment rates in two age groups. (I will forgo a more detailed explanation of my methodology here and focus on the results.)

A Green Light for Later Retirement

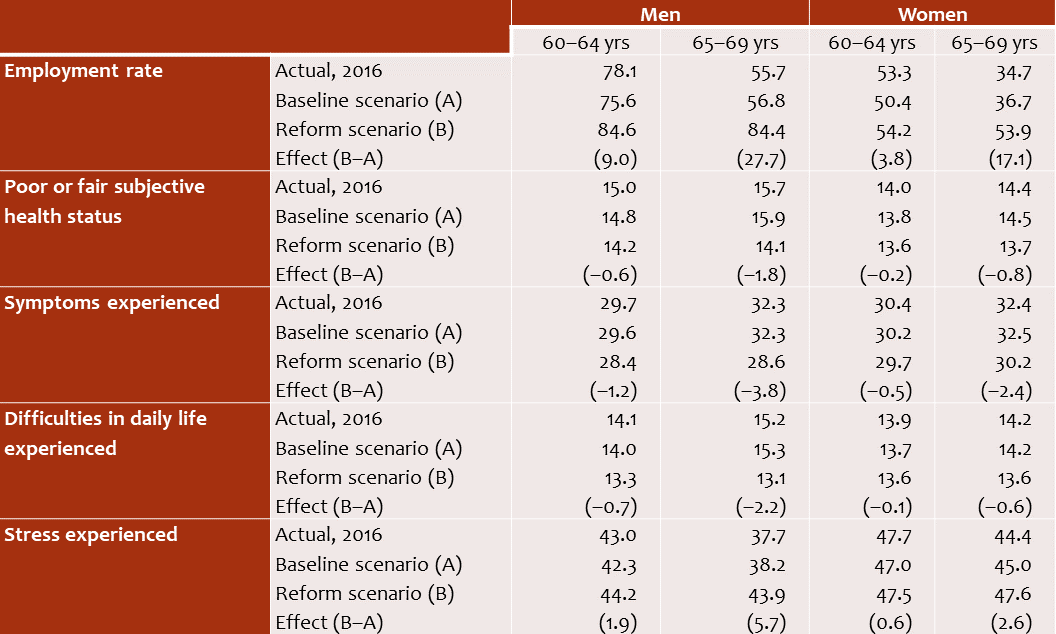

Generally speaking, my simulation indicates that raising the pensionable age to 70 would have little effect on the employment rate or health outcomes of those in the 60–64 age group; thanks to previous reforms, most of this population is already below the retirement age. However, among those aged 65–69, the employment rate increases by an impressive 27.7 percentage points among men and by 17.1 points among women.

Estimated Effect of Raising the Pensionable Age to 70

percent (percentage points)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions.

But what about health? In the 65–69 age group, the effect, though small, is generally positive. My simulation predicts a 1.8-point drop in the percentage of men reporting their own health status as fair or poor. Among women in the same age group, the decline is 0.8 points. The percentages of those reporting physical symptoms and difficulties in their daily lives also declines slightly under my simulation. On the other hand, the share complaining of stress goes up by 5.7 points among men and 2.6 points among women.

Leaving aside the stress factor, these results seem to provide statistical confirmation for the notion that working is good for you, even past the age of 65. Of course, these are rough calculations, and they only predict the average effect; individual outcomes vary substantially. Moreover, the results of my simulation suggest that delaying retirement could lead to an overall increase in mental health issues. Even given these stipulations, however, I believe it is fair to conclude that public-health concerns need not be an obstacle to raising the statutory retirement age in Japan.