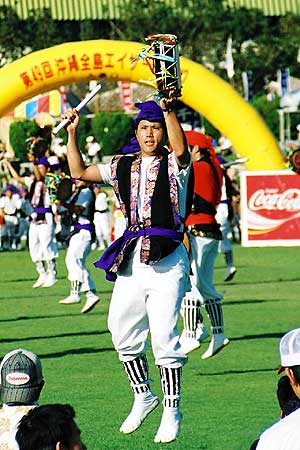

In recent years a uniquely Okinawan style of folk dancing known as eisa has become popular throughout Japan. Like much Japanese folk dancing, eisa is associated with the summer Bon festival, when the spirits of the dead are said to mingle with the living. Eisa is an integral part of an ancient observance in which the Japanese welcome their visiting ancestors, dine and dance with them, and send them off to the spirit world.

A great variety of Bon dances and ceremonies have evolved over the centuries, but the earliest practices were probably similar to those preserved even now on the island of Kohama in the Yaeyama Islands of Okinawa Prefecture.

During the Bon festival, young people divide into two groups that make their way through the community at night, going from house to house dancing and playing traditional sanshin (three-stringed instruments) and drums. At every house they stop and perform dances and songs related to the nenbutsu chanting of Pure Land Buddhism. Each household leaves its outer doors and gates open for the dancers and offers them food and sake in the garden when the dance is over. This is the Japanese festival in its purest form—performed for the sake of the villagers, not as a tourist attraction.

The same is true of Okinawa's Honen matsuri , the harvest festival. On Ishigaki Island, the Honen festival is still considered such a sacred and secret rite that no photos or sound recordings are permitted; even speaking or writing about what one has seen is technically forbidden. Like the Bon festival, the event marks a mingling of the spirit world with the world of the living. In this case, the gods are welcomed into the community, honored, and then seen off as they return to the ocean where they dwell.

Authentic festivals like these still exist here and there around Japan. More than 100 small rural communities on the island of Sado in Niigata Prefecture continue to perform the oni-daiko —an ancient drumming ceremony intended to ward off demons—though very few outsiders are aware of it. Rural Akita Prefecture preserves an ancient dance called bangaku , a melding of kagura (a Shinto tradition) and a type of dancing practiced by reclusive Buddhist mountain monks. At the last reckoning, bangaku survived in more than 140 communities, and while those numbers have doubtless dwindled, the dance continues to be performed, in some locales with great skill and sophistication. Almost no outsiders come to observe; these are festivals oriented exclusively to the local rural community.

Okinawa preserves an especially rich festival heritage, thanks in large part to its seinendan , or youth groups. Seinendan can be traced back to the wakamono-gumi of the Edo period (1603–1867), which played a key role in disaster assistance as well as such cultural events as festivals. Organizations known as za , groups of elders responsible for the upkeep of shrines, were also involved. However, without the youth, there was no practical way to keep these events going. In recent decades many Japanese communities have lost their young people to the cities, causing the average age of the residents to climb, and in such villages and towns it has become difficult or impossible to maintain the local festival traditions. In Okinawa, however, the seinendan remain very active, encouraging children to participate in local festivals and teaching them to perform the traditional music and dance.

In the Edo period, festivals were supported not only by youth groups but by a whole patchwork of small organizations. Some, like the wakamono-gumi , were based on age and gender, but there were also organizations created for more specific purposes, known as ko and yui . The first ko , formed in connection with the spread of Buddhism in rural Japan, were groups that gathered to recite the nenbutsu , a simple Buddhist chant. In time, however, ko were organized for joint financing of various projects, care of orphans, and more. The yui were ad hoc groups formed to cooperate on tasks such as funerals, the building of homes, or the repair of thatched roofs, but the ko gradually came to perform comparable functions

The groups that made up the typical rural community also helped manage the community's economic interaction with the outside world. In the Edo period, such interaction played an important role in rural life. Having learned new and improved methods of fertilization, farmers relied on merchants to bring them night soil, dried sardines, and other fertilizers from the outside. Villagers who made a living from weaving, paper making, or other crafts needed to take their products to market. Thanks to their self-governing organizations, communities were able to pursue and manage commerce and trade with the world outside in a way that benefited them economically

Among these groups, however, the wakamono-gumi were especially important. Since the members responded to disasters of all sorts, a village's very survival depended on the strength and cohesion of its wakamono-gumi . And as the organizations with responsibility for village festivals, the wakamono-gumi offered children and youth a place to learn customs and skills and develop community ties. In the process of passing on the traditions and know-how associated with local festivals, young people matured and became full-fledged members of the community.

The festivals themselves played a vital role in the life of the community. To begin with, they marked the turn of the seasons, on which most economic activity hinged. In addition to agriculture, which involved a series of sophisticated processes carefully attuned to the time of year, villagers followed seasonal cues in managing their coppice woodlands, which they harvested for fuel in the form of firewood and charcoal; building materials in the form of lumber and thatch; and various edibles, such as mushrooms that were dried and preserved. Known as iriaichi , or commons, these woodlands were managed and used jointly by the entire village.

Well aware that the woodland resources regenerated themselves over the course of the seasonal cycle, villagers were careful to harvest in moderation and at the appropriate time of year to ensure that there would be plenty the following year as well.

Festivals punctuated each season and each phase in the life cycle of the village, while providing important opportunities for villagers to come together, educate and socialize the younger generation, and pray for success in the year to come.