- Article

- Comparative and Area Studies

A Theoretical Study of Security Exchange: Toward a New Era in Japan-China Relations

December 10, 2012

While political tensions between Japan and China invariably receive front-page media treatment in both countries, the public has heard little about the progress our two nations have made in building mutual trust through bilateral exchange in the sensitive realm of security and defense. In a recently published book [1] on Japan-China security exchange , funded by the Sasakawa Japan-China Friendship Fund, co-editor Masahiro Akiyama (then chairman of the Ocean Policy Research Foundation; now president of the Tokyo Foundation) discusses , in the book’s lead chapter, the theory and significance of security exchange as a form of cooperative security and suggests ways to make such interaction more meaningful and productive.

Introduction

In the two decades since the end of the Cold War, great effort has been made to enhance security dialogue, defense exchange, and confidence-building measures in East Asia. The ASEAN Regional Forum, or ARF, has been the main focus of multilateral security dialogue in the region, but bilateral security exchange among East Asian nations has also been active. Japan, for its part, has pursued and carried out security exchange with a number of neighboring countries, including South Korea, Russia, and several Southeast Asian nations. But the biggest challenge for Japan has been how to develop defense exchange with China.

In the following, I will begin by examining the nature and purpose of security and defense exchange in general. Are the aims being adequately met? How does such exchange relate to existing international security frameworks? What security functions is it expected to perform, and is it performing them?

Next, I will discuss bilateral security and defense exchange from a theoretical perspective, focusing on the role of such exchange between Japan and China. Finally, on the basis of my conclusions, I will offer my own recommendations for enhancing the value of Japan-China security exchange.

Defining Security Exchange

In order to examine security and defense exchange from a theoretical perspective, we must begin by defining the term. The broadest definition would be “interaction of any type between nations in the security or defense sphere.” As used in Japan, however, the term is generally limited to interaction between countries that are not already allies or strategic partners. “Security and defense exchange” (or simply “security exchange”) as used here does not apply to interaction between Japan and the United States, since the two nations are allies.

Security exchange can take place within a bilateral or multilateral framework, but the vast majority of analyses to date have focused on multilateral exchange, and theoretical discussions of bilateral exchange are almost nonexistent. Later I will attempt to remedy that situation by focusing on bilateral security exchange—specifically, that between Japan and China.

Security exchange typically takes the form of security dialogue, staff talks, unit-level military exchanges, reciprocal visits by military officers, and interaction in the area of research and training. Unit-level military exchanges can include reciprocal ship visits, joint exercises, reciprocal troop visits, or interaction between units in the context of peace-keeping operations. The majority of such activities are regarded as confidence building measures or are undertaken with a similar impact in mind.

The Japanese word for defense exchange ( boei koryu ) has no equivalent in Chinese, the closest being fangwu jiaoliu , which refers not only to security exchange with nonallied countries but also to that with key strategic partners, such as Russia, and military diplomacy, including military aid. Indeed, military diplomacy with the developing nations of Africa figures prominently in China’s fangwu jiaoliu policy. This difference in terminology complicates any comparison of the two countries’ security exchange policies.

For the purposes of this analysis, however, I will focus on the type of interaction that corresponds to security exchange as defined above. This definition excludes exchange with the United States, with which Japan has an alliance, and also excludes the Chinese notion of “military diplomacy,” since Japan currently has no such program. A deeper examination of the difference between the Japanese and Chinese concepts must await another occasion.

The Purpose of Security Exchange

The foregoing definition describes security exchange as a phenomenon, but how should we understand it in terms of objectives and functions?

The basic unit in the global system remains the nation-state, and the peace and prosperity of humankind is profoundly affected by how these nations relate and interact with one another. It goes without saying, therefore, that cultivating and maintaining good relations between nations is a matter of the utmost importance.

Cultivating and maintaining good relations among nations naturally requires sound foreign policies on the part of each government, but another key component is various types of exchange between nations, at both the official and the nongovernmental levels. This may entail cooperation in the pursuit of shared goals, as when the police of different countries collaborate in crime prevention or law enforcement. However, in this analysis, we focus more on the type of dialogue and people-to-people exchange that is aimed primarily at laying a groundwork of mutual trust and understanding on which to build good relations. This is much the same function pursued by governmental and nongovernmental international exchange initiatives in other fields, including culture.

It goes without saying that exchange in the arena of defense and security also contributes to building mutual trust and understanding, so, in that sense, it can be likened to other types of international exchange.

But it also has other dimensions, for it involves organizations and personnel—both in the governmental and nongovernmental sectors—that are directly or indirectly engaged in combating external threats through the use of military force. Building mutual trust and understanding in the defense sector, whose very existence is predicated on the possibility of armed conflict, has a special significance for the cultivation of good relations, but it also poses special challenges. Between nations that are neither allies nor de facto strategic partners—and may even become potential enemies—interaction and exchange in the military sector can be critical to the development of friendly ties. But such interaction and exchange cannot occur between such nations unless they are vigorously pursued.

In this sense, security exchange is more than just another form of international exchange. In addition to the general objectives of confidence building and mutual trust, security exchange has a more specific goal, that is, the achievement of common goals for national security. That said, it can be quite difficult for countries that are neither allies nor strategic partners to agree on common security goals. This is a topic that must be discussed with reference to the “security framework” theory.

In April 2007 the Japanese Ministry of Defense issued its Basic Policy for Defense Exchange. [2] Under the heading of “Significance and Purpose,” the document notes that, “while the overriding role assigned to defense exchange was initially that of confidence building with neighboring countries so as to prevent accidental military clashes, expectations have changed. Today it is widely understood that the main significance of defense exchange lies not only in confidence building but also in the building and strengthening of cooperative ties with the international community.” It goes on to say that the “general significance and purpose” of defense exchange are to cultivate mutual understanding, build confidence, and promote friendly relations, while the “concrete significance and purpose” are to deal with specific security issues.

The Defense Ministry is to be commended for acknowledging that security exchange has more concrete objectives than the general goal of confidence building, but the document devotes only a few lines to the importance of “resolving security concerns (preventing the emergence of destabilizing factors)”with unfriendly states while dwelling at length on the general purpose of “strengthening cooperation with friendly countries.”

My aim in analyzing security exchange from the standpoint of security framework theory is to highlight precisely the concrete objectives that the Basic Policy for Defense Exchange neglects, and in so doing, shed light on the role of security exchange between nations that pose a potential security threat to one another.

Types of Security Frameworks

Security frameworks are generally divided into four categories: conventional, collective, common, and cooperative. While some also speak of “comprehensive security” and “human security” as separate categories, these four types of security framework will be sufficient for our purposes here.

Conventional security refers to the national defense systems that rely on military resistance and/or deterrence to protect a nation’s territory and independence, as well the lives, physical well-being, and assets of its people from the threat of external aggression, whether by means of resistance or deterrence or both. Military alliances, which are an extension of this type of defense, are the basic international framework for conventional security. Because international society consists of sovereign states that are not subordinate to any higher governing power, a nation has no choice but to exercise its own right to self-defense in the event of an armed conflict. Until some other security model becomes fully functional, conventional security systems will remain the final resort.

Collective security is the aim of the United Nations (and the League of Nations that it replaced). In the event that any one member state commits an act of aggression against another, the other members respond as a group to counter it, first with sanctions and ultimately, if necessary, with collective military force. The United Nations, however, does not yet have the standing army that was envisioned in the UN Charter. Furthermore, the Security Council, the UN’s supreme decision-making body for security issues, has an extremely poor record when it comes to making and enforcing meaningful security decisions, owing to the fact that each of the permanent members has veto power. On the other hand, some have argued that the UN is in effect performing its collective security function when member states voluntarily cooperate in military action in response to a Security Council resolution, or when the General Assembly passes a resolution establishing peacekeeping operations or other frameworks for collective security. It should also be noted that the UN Charter recognizes the right of members to engage in individual or collective self-defense and assumes the eventual emergence of regional security institutions.

Common security, developed in Europe during the Cold War, was a product of that particular era in history. As the United States and the Soviet Union built up their nuclear arsenals, their respective allies in Western and Eastern Europe grew increasingly alarmed that a military conflagration could reduce the region to ashes. These common concerns gave rise to the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe—the predecessor of today’s Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe—in which fundamentally hostile nations joined together to develop confidence-building measures aimed at averting war. Among these confidence-building measures were advance notification of large-scale military exercises and troop movements, reciprocal observation of military exercises, a pledge to refrain from provocatively aggressive armament or arms deployment, and the establishment of a security hotline.

The development of a security framework after the end of the Cold War was no longer pursued in common security terms. As tensions between East and West dissipated, the CSCE was reconstituted as the OSCE, which embodies the kind of cooperative security arrangement that emerged in the post–Cold War era.

Cooperative security uses security dialogue, military exchange, and confidence building among multiple countries, including potential adversaries, to prevent armed conflicts and clashes in an international environment in which security threats—including “enemies”—are ill-defined. Following the Cold War, many countries of Eastern and Western Europe, which were not allied with one another, came together under the cooperative framework of the OSCE with the purpose of averting armed clashes among the member states. In Asia, a cooperative security system is being pursued by the ASEAN Regional Forum, another product of the post–Cold War era.

The “security exchange” discussed in this and other chapters of the book clearly falls into the cooperative security category. However, there may be some question as to whether bilateral exchange qualifies as a “cooperative security” arrangement, since most such systems are multilateral. This is a question that will be dealt with later; I will first look more closely at the functions and characteristics of cooperative security.

Cooperative Security Systems

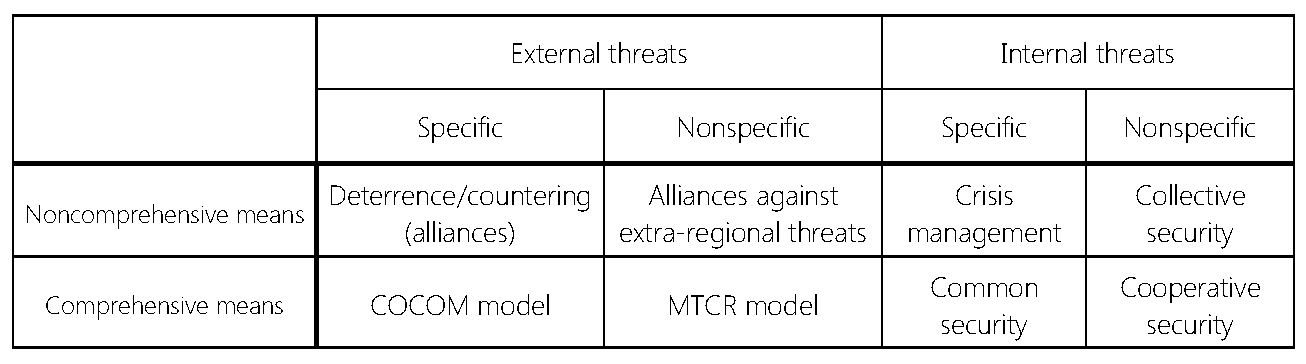

How should we characterize cooperative security in terms of its functions, conditions, constituents, and so forth? In the 1990s, Yoshinobu Yamamoto proposed a classification of security systems based on three sets of criteria: whether the threat is specific or nonspecific, whether it comes from inside or outside of the system, and whether the means used to counter it are predominantly military (noncomprehensive) or include political, diplomatic, and other measures (comprehensive). Since Yamamoto devised his classification for the purpose of comparing and contrasting cooperative security with conventional, collective, and common security systems, let us begin by examining cooperative security from his perspective. [3]

Yamamoto used a chart similar to Table 1 to summarize his classification of international security systems.

Table 1. Classification of International Security Frameworks

Under this classification, conventional security systems are characterized by specific, external threats and a reliance on military means to address those threats. At the other end of the spectrum is cooperative security, defined by nonspecific, internal threats addressed through comprehensive approaches. Common security uses comprehensive means to counter specific, internal threats, while collective security (theoretically) would use military means to counter nonspecific internal threats. By “specific threats,” Yamamoto is referring to the type of situation that existed during the Cold War, when the nations of the Eastern bloc were aligned against those of the West and vice versa. “Nonspecific threats” describes the amorphous security situation that arose after the East-West conflict came to an end.

Under Yamamoto’s classification, then, cooperative security is a system adapted to a situation in which the enemy is indeterminate. It is a system in which participating countries might be either friends or potential enemies. In this sense, it differs decisively from the Cold War common security system under which the East-West divide was clear cut.

The question Yamamoto’s chart fails to answer, though, is how to deal with nontraditional threats, such as terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, piracy, and so forth. These are not threats that one nation poses to another, and would therefore not ordinarily lead to war. [4] Nonetheless, they often call for a military response. The fact is that Yamamoto devised his classification in 1995, before there emerged a strong consciousness of nontraditional threats. Because his key criteria focus on the presence or absence of a clearly identifiable conflict between nations, it is difficult to accommodate nontraditional threats in this system. In the following, however, I discuss them as nonspecific threats, since I believe they are particularly important in relation to internal threats, which I discuss next.

Neither the OSCE nor ARF were conceived to counter external threats; they were designed to head off the threat of conflict among members through frequent dialogue, exchange, and other confidence-building measures. Some of Europe’s biggest external security threats today are not actively directed at Europe but are developments that have the potential of affecting the region—civil war, transnational terrorism, piracy, and so forth. Countering such threats is the task of NATO and the European Union. The OSCE, on the other hand, is a cooperative security framework dealing with potential conflicts among its members.

Moreover, in case nontraditional threats materialize internally, it seems perfectly reasonable to deal with them using cooperative security arrangements, even if they are transnational in nature. When one realizes that nontraditional threats encompass not only terrorism and piracy but also the displacement of persons for political and economic reasons, smuggling of workers and goods, outbreaks of infectious diseases like avian influenza, and large-scale natural or environmental disasters, one can see how a cooperative security system could be an effective framework to deal with such threats. In fact, the ARF is currently deliberating measures to counter piracy and other new threats to maritime security.

Both the OSCE and ARF are made up primarily of countries lying within a certain geographical region, but regionalism in a narrow sense is not their ruling principle; after all, the ARF’s current participants include the European Union and the United States. “Regional” security frameworks need not be defined geographically; Sugio Takahashi prefers the term “local level” to signify a unit that exists between the national and the global levels but that is unconstrained by physical proximity. [5] This understanding will come into play later in this paper, as we explore possibilities for security exchange between Japan and China.

Cooperative security systems are built around nonmilitary responses, such as regular security dialogues, defense exchanges, and other confidence-building measures—none of which rely on military force. For this reason, cooperative security systems are limited in their ability to deal with outbreaks of military aggression or armed conflict. In such cases, countries need to resort to individual self-defense, collective self-defense, a collective security arrangement, or some combination of the above. Proponents of cooperative security, it should be noted, do not exclude these other approaches. In fact, some maintain that cooperative security systems and coercive systems based on military force should be approached as two sides of a coin. [6] Indeed, even if these systems can be isolated conceptually, any pragmatic policy must be predicated on their coexistence. This suggests that, for a cooperative security grouping to function effectively, it must include among its members at least one major military power. The fundamental purpose of cooperative security is, in a nutshell, to build confidence among member states through nonmilitary measures and head off armed conflicts before they occur.

A Theoretical Approach to Security Exchange

With this theoretical framework in mind, let us now return to our main topic: security exchange. If one places such exchange into one of the four frameworks discussed above, it would clearly be in the category of cooperative security. But we must probe more deeply to establish whether bilateral security exchange between Japan and China—our ultimate focus here—can truly be considered part of a cooperative security system.

The first question to address is whether bilateral arrangements in general can be considered a type of cooperative security. Technically speaking, a bilateral arrangement is multilateral. However, in actual discourse bilateral and multilateral approaches are typically treated separately. In the context of international relations, bilateral and multilateral frameworks are understood to differ in their purpose and function. And the fact is that theoretical discussions of security frameworks almost never focus on bilateral cooperation and exchange. How can we account for this?

In the security field, bilateral exchange is generally conducted for the purpose of building mutual trust and understanding. This aspect of bilateral security exchange pertains whether the countries involved are friends or potential enemies. In the case of potential enemies, however, bilateral exchange can also function to facilitate crisis management. [7] The idea here is to lay the groundwork for prompt information sharing to avert misunderstandings and ensure that, should a dispute or emergency arise between the two countries, they will be able to resolve it peacefully and avert any military clash. Concluding an agreement on maritime accidents is a good example of this sort of structure. [8]

Multilateral exchange, on the other hand, tends to focus on building institutional mechanisms and frameworks that are typically associated with cooperative security systems: councils and other bodies dedicated to averting conflict, multinational review of national defense policies and programs, procedures for conflict resolution, and so forth. But such frameworks are difficult to achieve precisely because of their multinational character. In the real world, accordingly, interaction geared to crisis management and policy dialogue is apt to be carried out on the bilateral level. When it comes to cooperative security, therefore, there is no sharp conceptual distinction between bilateral and multilateral approaches.

Bilateral exchange, in fact, has certain advantages over multilateral exchange. Reaching an agreement between two countries is easier, and the two countries can launch an exchange program immediately after an agreement is concluded. Where security dialogue is concerned, it is quite possible to carry out a substantive discussion on issues of bilateral concern; indeed, such dialogue is likely to be more effective and productive than a multilateral discussion. It follows from this that the pursuit of cooperative security at the bilateral level could serve as an important first step toward the goal of a multilateral cooperative security system. From this perspective, it seems reasonable to place both bilateral and multilateral exchange in the category of cooperative security, even while acknowledging differences in the way they function.

The next question to explore in discussing bilateral security exchange programs as a cooperative security system is the specificity of the threats encountered. Even in the case of two countries that are latently hostile, the potential security threats are obviously not concrete and identifiable in the same sense that they were during the Cold War.

In some instances, in fact, countries conduct bilateral security exchange programs even though they have no issues to speak of with one another. Japan, for example, has defense exchange programs with Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and various European nations. This is not to say that Japan has no issues whatsoever with these countries, but there are not even nonspecific security threats to speak of with these countries. Security exchange with such countries should be considered not so much in a security framework as a category of diplomacy, a way of promoting international cooperation to deal with more general global or regional threats. I have stipulated that Japan has no program of military diplomacy at present, but this kind of exchange can be thought of as a form of intergovernmental diplomacy that involves both countries’ defense establishments. The Basic Policy for Defense Exchange actually treats such interaction as an important component of Japan’s defense exchange program, but such bilateral exchanges, as noted earlier, do not fit neatly into existing security frameworks.

Regarding Japan and China, neither nation poses a specific, identifiable security threat to the other. But neither are they strategic partners or “friends,” in the sense of countries with broadly overlapping national interests. Any potential threats here are nonspecific and nontraditional.

As Japan explored the possibilities for security exchange in the post–Cold War years, initiatives aimed at building confidence and fostering mutual understanding with China made conspicuously slow progress. Relations between Japan and China are fraught with political tension, which raise formidable hurdles to bilateral exchange in the security sphere. Given the politically fraught nature of this bilateral relationship, it seems reasonable to assume that crisis management is one of the purposes of Japan-China bilateral exchange. It is worth noting that the two countries have yet to conclude an agreement on maritime accidents.

In fact, one can envision a number of scenarios capable of triggering a security crisis between China and Japan, including situations relating to the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, development of energy resources on the continental shelf, and military activity in the exclusive economic zone, as well as various nontraditional threats. These are exactly the kinds of crises that bilateral security exchange can avert or defuse. In other words, bilateral security exchange between Japan and China is (or should be) concerned with more than general efforts to build mutual trust and understanding. Only in a relationship such as that between Japan and China—in which both countries are conscious of nonspecific bilateral security threats—can bilateral security exchange be understood as a kind of cooperative security framework.

Now we come to the question of whether the potential threats in a bilateral security relationship should be treated as external or internal to the security framework. While the immediate impulse is to call them external, from a theoretical standpoint, they are internal, as they are addressed by either multilateral or bilateral cooperative security frameworks. In the case of Japan and China, the purpose is to prevent crises from emerging or escalating through dialogue, exchange, confidence-building mechanisms, and other joint action. It is not to resolve full-fledged conflicts after they have broken out. Were hostilities to break out between Japan and China, we could not expect the two countries to resolve the conflict by means of a joint response under a bilateral cooperative security arrangement. In such an event, an effective response would have to occur in conjunction with a traditional or collective security framework.

Bilateral security exchange does not involve the use of military power. Instead, it uses nonmilitary means like dialogue, exchange, and confidence-building measures in the security sector. Under Yamamoto’s framework, cooperative security systems rely also on exchange in other sectors, particularly the diplomatic, economic, and social spheres. While such interaction certainly plays an important role in security, including them in our discussion here can interfere with our attempts to identify the function and character of bilateral security exchange. Here, I would like to focus on exchange in the security and defense domains.

Assessing Japan-China Security Exchange

At present, security exchange between Japan and China appears to be limited to interaction aimed at the general goals of international exchange, namely, building mutual trust and understanding. Owing to historical factors, differences in national character, conflicting political systems, and both countries’ positions as major Asian powers, the bilateral relationship between Japan and China is a difficult one, and for this reason it is understandable that the initial focus should be on building mutual trust.

But building trust is particularly challenging when the actors involved are military or defense-related personnel—including researchers in the private sector—whose roles are predicated on the possibility of war as a last resort for protecting national interests. We must scrutinize Japan-China security exchange closely to determine whether it is achieving its general purpose when viewed from this perspective. To keep the discussion manageable, I will focus on the more specific aim of building confidence between our two nations’ defense establishments.

The security exchanges initiated between Japan and China after the end of the Cold War—however belatedly—have certainly contributed something to the general goal of international exchange, building mutual trust and understanding. In terms of “track 2” (nongovernmental) interaction, the periodic security dialogues and exchanges between defense personnel carried out under the auspices of the Sasakawa Japan-China Friendship Fund have played a particularly important since it was inaugurated in 2000. With just one exception, exchange activities have continued as scheduled, even amid mounting political tension. In terms of fulfilling the aim of enhancing mutual understanding, it has been far and away the most effective undertaking of its kind.

Taking this program as a case in point, I would like to suggest certain ways in which we could enhance the confidence-building efficacy of Japan-China security exchange. One way would be to shift the emphasis from field trips at present to the exchange of opinions on national defense strategy. Other options include improving military transparency through mutual disclosures of weapons and military equipment, promoting exchanges of units, bringing together senior officials to share views, and, if possible, conducting joint operations of some sort.

I would also suggest that exchange is more effective when there is a follow-up program. After an event or activity, the participants should continue to network and strive to meet again periodically, even if only at intervals of several years. International exchange is only meaningful if we continue to nurture the seeds of mutual trust that have been planted. Keeping detailed records of the proceedings and publicizing events through the media would also enhance the effectiveness of such security exchange.

Upgrading the Security Framework

Now let us consider how bilateral security exchange in general, and Japan-China exchange in particular, can achieve the more concrete aims of a cooperative security system. My focus will be on the nature of threats and their internalization within the security framework.

We have seen that cooperative security deals with nonspecific threats. Where China and Japan are concerned, though, various issues do exist between the two countries that pose a latent threat: the situation on the Korean Peninsula, the Taiwan problem, and territorial disputes in the South China and East China seas, not to mention nontraditional threats relating to the environment, fisheries, illegal immigration, smuggling, trafficking, and so forth. That said, the situation is certainly a far cry from that which persisted during the Cold War, when much of the world could be clearly identified as either friend or foe, and an armed conflict had the potential to escalate into a world war.

When addressing latent threats of this sort through international cooperation, crisis management is of the essence. Two countries working one on one through a bilateral security exchange program should find it easier than a large group of countries to build a joint crisis management system. They could begin by regularly scheduling exchanges and promote the establishment and use of a hotline and similar crisis-management mechanisms. Inviting the United States into the dialogue, as I will elaborate below, would also make a major contribution to enhancing crisis-management effectiveness.

The treatment of security threats as internal issues is unusual where Japan and China are concerned, but we should not avoid discussion of such a crucial matter. Unfortunately, Japan’s Basic Policy for Defense Exchange devotes insufficient attention to the subject.

In the context of Japan-China security exchange, internalization would mean treating all the latent threats discussed above not as external to the relationship but within it, to be addressed jointly through the bilateral framework. Other nonspecific threats, such as terrorism, piracy, proliferation of WMD, and large-scale natural disasters, may be classified either as internal or external, depending on where and how they arose. If they are external, Japan and China can agree to act jointly within the framework of a UN peacekeeping or other international operation. This would mean joint participation in a multilateral collective or cooperative security system. However, such threats may also emerge within either country, in which case they would be addressed as internal issues.

There do not exist, though, any formal exchange mechanisms to deal with internal security threats. The only existing approaches are dialogue, military exchanges, and confidence-building measures. The key would be to recognize the internal nature of the threats and to share an awareness that heading off or resolving them peacefully is built into the system for bilateral security exchange. Of course, any full-blown contingency would necessitate the involvement of other security frameworks, as explained above. But in any situation short of such a contingency, Japan-China security exchange would play a vital role when security threats are internalized.

This brings us back to a point I made previously—the importance of having a major power participating in any cooperative security arrangement. China, of course, is a major power. However, the major power for security in the Asia-Pacific region is the United States. The United States also happens to be an ally of Japan; indeed, the Japan-US alliance is the biggest security framework in the region. And since regional security frameworks need not be subject to rigid geographical constraints, as explained previously, there is nothing unnatural about US involvement in a security system focused on East Asia or in a framework for security exchange between Japan and China.

From a practical standpoint, moreover, any serious security threat confronting China and Japan will need to be addressed by China and the Japan-US alliance. And for a cooperative security system focused on Japan and China to function effectively, US participation would be a major factor. It might be argued that China would regard the involvement of Japan’s ally as a threat in itself. But China and the United States have been pursuing their own military exchanges, a key purpose of which is to address internalized threats. Under these circumstances, there is no reason for China to regard US involvement as an additional threat. Bilateral exchange need not go any further if it is primarily aimed at promoting goodwill, but considering the nature of the threats the two countries confront and their internalization, perhaps it is time to expand the dialogue to include the United States as well.

This can be advanced as a trilateral framework among Japan, China, and the United States or a bilateral one, between China on the one hand and the Japan-US alliance on the other. In the past, China had been reluctant to enter into a trilateral dialogue on the grounds that it would invariably be outvoted. It also hoped to resolve issues relating to the US presence in East Asia bilaterally, between Beijing and Washington. But the United States would be hard-pressed to project its military power in the region without Japan’s defense capability, the use of military bases in Japan, and the support of the Japanese government. The US naval fleet, in particular, relies heavily on antisubmarine patrols by Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force. From a practical viewpoint, then, China’s hypothetical adversary is the Japan-US alliance. If Beijing objects to a trilateral framework, then a bilateral arrangement—with the Japan-US alliance represented as a single party—might be the best solution. [9] It is high time to begin building a cooperative security system involving Japan, the United States, and China.

The foregoing explored security and defense exchange from a theoretical perspective and offered proposals for how Japan-China security exchange can be advanced in the future. Full-scale exchange incorporating crisis-management elements at the government level will doubtless take time. Initiatives can begin, therefore, at the nongovernmental level—either track 1.5 or 2—and later evolve into government-to-government exchange. China admittedly may resist a trilateral dialogue that includes the United States, but it is nonetheless in Beijing’s interests to craft a crisis-management system of some sort with both Tokyo and Washington. Insisting on bilateral talks—perhaps with a view to isolating the allies—will only accentuate the confrontational elements in the relationship with Beijing and result in strengthening the alliance. In fact, it could actually invite a security dilemma.

The Asia-Pacific region as a whole, moreover, would like nothing better than to see measures to enhance trust among Japan, China, and the United States. Such a framework for cooperative security exchange would also have the potential to go well beyond general confidence-building and address substantive security issues, namely, transparency in China’s defense program and military deployments, arms control and arms reduction, and nontraditional security threats.

With regard to the transparency issue, if Beijing steadfastly refuses to lift the veil of secrecy surrounding its defense program, it will end up plunging the security players in the region into the “prisoner’s dilemma.” In other words, Japan and the United States will be dragged, against their will, into an East Asian arms race. The fact is that Japan and the United States are already moving to bolster their defense capabilities to deal with China’s growing military power. But surely an arms race is the last thing Beijing wants. China’s military establishment may believe it can leverage the supposed threat of the Japan-US alliance to expand the defense budget indefinitely, but at some point the spending spree must end—particularly given the labor and revenue shortages the nation will face after around 2030, when its population is expected to peak.

When assessing the prospects for arms control, we should recall that even at the height of the Cold War, Washington and Moscow came together on the need to limit deployment of anti-ballistic missile systems that threatened to undermine the deterrent of “mutual assured destruction” and spur a renewed arms race. The deployment of increasingly sophisticated intercontinental missile defense systems in East Asia poses similar arms control challenges for China and the Japan-US alliance. China is reaching the stage at which single-minded military expansion must give way to efforts toward international arms control. Arms control negotiations require a certain level of mutual trust to succeed, but substantive arms-control talks can also serve to build mutual trust.

China also risks triggering an arms race with Taiwan, as Taipei responds to the ongoing buildup of Chinese attack missiles aimed across the strait by strengthening its missile defenses, and possibly by deploying offensive missiles of its own.

When it comes to dealing with nontraditional security threats, international cooperation is vital not only to reduce the cost burden on individual nations but also to ensure that countermeasures are implemented in an effective manner. Japan and the United States are already cooperating actively in this sphere. Since the turn of the current century, the United States has become far more actively involved in addressing these threats, including natural disasters—something it basically ignored as recently as the mid-1990s. Any concrete cooperation among Japan, China, and the United States in this area—particularly in the context of actual operations, as opposed to drills—would contribute immensely to nurturing mutual trust.

I am convinced that Japan, the United States, and China need to hold repeated dialogues on the issues outlined above, even if they are initially held at the nongovernmental level.

[1] Masahiro Akiyama and Zhu Feng, eds., Nitchu anzen hosho–boei koryu no rekishi, genjo, tenbo (Past, Present, and Future of Japan-China Security Exchange), (Tokyo: Aki Shobo, 2011).

[2] http://www.mod.go.jp/j/defense/exchange/01.html

[3] Yoshinobu Yamamoto, “Kyochoteki anzen hosho no kanosei: Kisoteki na kosatsu” (The Potential of Cooperative Security: Fundamental Considerations), Kokusai Mondai 425 (August 1995): 3–10.

[4] A notable exception was the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The 9/11 attacks led to the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, whose government had harbored the al-Qaeda terrorist organization.

[5] Sugio Takahashi, “Kyochoteki anzen hosho gainen no saiteigi to Ajia-Taiheiyo ‘chiiki’ no anzen hosho,” (Redefinition of Cooperative Security and Security in the Asia-Pacific “Region”), Boei Kenkyujo Kiyo (NIDS Security Studies) vol. 2, no. 2 (September 1999): 30–31.

[6] Takahashi, “Kyochoteki anzen hosho gainen no saiteigi,” 39.

[7] Yamamoto, “Kyochoteki anzen hosho no kanosei,” 4–5.

[8] Japan and Russia signed such an agreement on October 13, 1993.

[9] See Benjamin L. Self, “An Alliance for Engagement,” in Benjamin Self and Jeffrey Thompson, ed., An Alliance for Engagement: Building Cooperation in Security Relations with China (Washington, DC: Henry L. Stimson Center, 2002), 145–64.