- Article

- Comparative and Area Studies

Community Building or Collective Balancing?: A Japanese Perspective

July 2, 2012

Introduction

The Obama administration has strongly forged a strategy of a US “return” to the Asia-Pacific. Since taking office, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has repeatedly emphasized that position, making more trips to the region than her predecessors. In July 2010, she attended the ASEAN Regional Forum, where she confirmed US support for the freedom of navigation and open access to maritime commons in the South China Sea, calling for a resolution to disputes in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a stance on which the foreign ministers of the 10 nations concurred. And, the US commitment to the Asia-Pacific region was repeatedly acknowledged and emphasized in speeches by US senior officials.

In Canberra, President Barack Obama reconfirmed his commitment to this region for security, economic prosperity, and human rights as a Pacific nation. [1] Also, Secretary of State Clinton has written on the importance of Asia policy and outlined six pillars of that policy: strengthening bilateral security alliances; deepening cooperative relations with China and other emerging nations; engaging in the region’s multilateral institutions; expanding trade and investment; pursuing a broad-based military presence; and strengthening democracy and human rights. [2] The US alliance network and security cooperation with non-allied states have been striking recently, in addition to its participation in multilateral regional institutions.

Strategic Survey 2011 , published by London’s International Institute for Strategic Studies, noted that there were clear efforts by countries to try to balance China’s capabilities and strategic intentions by strengthening diplomatic and military cooperation with the United States, engaging China in multilateral institutions, and acquiring their own military capability. The report concluded, “China’s military expansion is a major factor contributing to the arms race that is clearly underway in Asia-Pacific.” [3]

It is said that China has started to be cautious about the impact of the US pivot to the Asia-Pacific. Will the Asia-Pacific end up being divided by the political and military competition between the US and China by the shift of balance of power? Or, will we see the development of regional community building that contributes to a more stabilizing order? Where do Japanese interests lie? This presentation will discuss Japan’s security strategy to answer these broad questions.

Japanese Strategy: Integration, Soft-Balancing, and Deterrence[4]

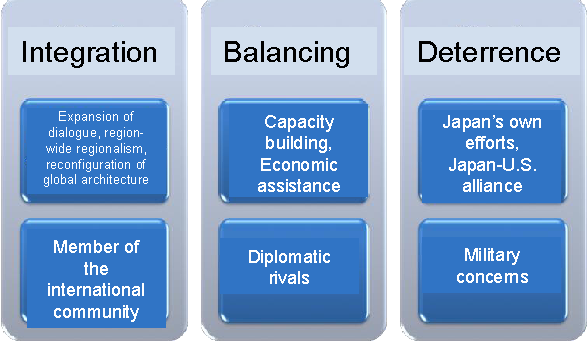

From Japan's perspective, for issues raised in the present and in the future by the rise of China, a China strategy should be advanced composed of integration, soft balancing, and deterrence in an appropriate combination. Given the premise that a power transition will occur, and in order to grapple actively with the new international environment to come, Japan must seek a balance such that China's growing political influence will not obstruct cooperation in regional and global dimensions.

To that end, partnerships with many countries are to be strengthened and, at the same time, integration is to be furthered by expanding the margin for collaboration with China. The growing military power of China is to be addressed by raising the level of deterrent readiness, to include heightened crisis management capability.

There are three images of China to be found in the background. The first image is of China's economic growth, which suggests responsibilities not of a developing country but rather that of a great economic power. China seen in this way engages it to take responsible actions as a member of the international community, and it should work not only for itself but also contribute to the stability and development of the international community.

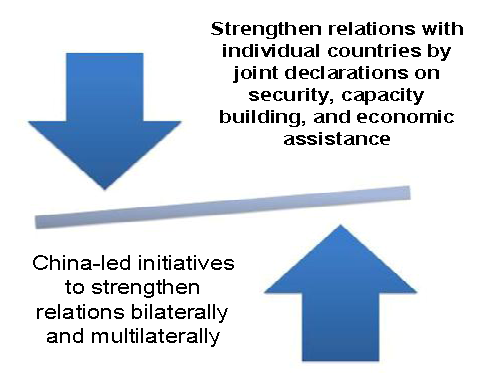

An integrated strategy oriented to that kind of purpose should not only seek to expand bilateral and multilateral dialogue with China but must also elicit cooperative actions in the Asia-Pacific regional order extending region-wide. Further, it is called on to realize the peace and stability of the international community within the G20, the IMF, the United Nations, and other such global architectural frameworks and to harmonize with efforts to address issues on a global scale (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Integration of China in the World Community

However, China does not necessarily display the actions of a responsible member of the international community either with respect to the formation of a region-wide order or with respect to cooperative action in the international community. It has engaged in selective cooperation with countries that satisfy its own preferences, and it has at times obstructed the formation of consensus. In the event that diplomatic rivals China and Japan do not agree on what order is desirable, then Japan will of course find it necessary to assure the benefit of the international community and to address the issues facing humankind in common by forming strategic partnerships with the US and other countries and to secure a balance along the axis of functional cooperation.

It should be noted now that what is intended here is not to achieve a balance in the sense of an equilibrium of forces, but rather (and entirely) in the sense that, if there were any elements that threatened the future of the international order in the formation of alliances under China's leadership, then balance would be sought through diplomatic competition with such elements. The strategic impetus of the US, Japan, and other countries with regard to China as a military threat is subsumed under deterrence (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Three Images of China and Strategy toward China

Balancing has the three patterns of hard balancing, soft balancing, and institutional balancing. Hard balancing consists of the consolidation of force (external balancing) to resist a dominant country and the strengthening of one's own countervailing power (internal balancing). The traditional balance of power approach advocated by realists in international politics corresponds to this hard balancing.

Soft balancing signifies coordination among multiple countries using non-military means (such as economics, diplomacy, and social influence) to limit the one-sided actions and influence of a dominant country. Institutional balancing is the activity of restraining a dominant country and reining in its activities in a multifaceted manner by engaging in the establishment, formation, or development of rules, international institutions, and forums of various kinds. Institutional balancing can be considered a derivative form of soft balancing, but the crucial difference is that the latter refers only to internalization of a dominant country within one's own institutions, while the former also includes placement of a dominant country outside the framework of an institution.

Balancing as used here corresponds to soft balancing and institutional balancing. Countries that take part in these forms of balancing may, when a clear threat surfaces, engage in hard balancing, which is to say, developing alliances in order to achieve a classical balance of power. That possibility cannot be excluded, but since the motives for forming alliances differ, it cannot necessarily be assumed that such alliances will develop automatically.

China is always setting out in its own way to strengthen security relationships centering on functional cooperation. This is taking place through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and primarily through bilateral relationships with Asian countries. There are aspects that even make it resemble the principal battlefield where competing diplomatic efforts are being made regarding security.

Taking this current state of affairs into account, in order to depict China in the image of a diplomatic rival and to form an international cooperation that is effective for the purpose of promoting the benefit of the region as well as of the international community, it will be useful to take an approach assuring cooperation that operates flexibly while also sometimes developing cooperative relationships that do not include participation by China, thus conversely inducing China's participation.

If the lever applied to the China intended by the latter approach successfully does what it is meant to do, then an integrated strategy with China may be expected to function. It is as though to say that elasticizing the security systems and arrangements that exist regionally to deal with actions by China is of the essence of the balancing strategy, and that it plays a role in supplementing the balancing strategy. Then the success or failure of the balancing strategy will depend on whether or not Japan is able to adequately mobilize the resources (economic power, diplomatic power, social influence, etc.) needed for Japan to position balancing directed at China as an effective security policy.

It is an unmistakable fact that China's growing military power is producing the image of China as a military concern. The progressive buildup of naval forces, in particular, coupled with the fact that China's maritime activities are clearly growing more aggressive, invites concern by the countries in the region. In the autumn of 2008, for the first time in Japan, four combatant ships of the People's Liberation Army Navy transited the Tsugaru Strait to proceed to the Pacific Ocean. Their course also took those craft through the waters between the main island of Okinawa and Miyako Island. Ships of the PLA Navy have passed through these waters repeatedly since that time. In 2010, the arrest of a captain of an illegal fishing vessel near the Senkaku Islands came as a great shock to the people of Japan, and military concerns about this incident were apparent among specialists from an even earlier stage.

There was intense concern about China's military rise in the US, as a result of which large volumes of excellent reports and testimony were made available from inside and outside the government. In 2009, PLA Navy ships and fishing vessels approached the US Navy sonar surveillance ship Impeccable , and some of them interfered with its passage in an incident that heightened military concerns at sea. The increased level of operations by China in the South China Sea not only heightens territorial conflict but also is taken as a challenge to the freedom of navigation. The question of how to resolve the problem is undergoing heated debate.

China's military power has demonstrated major advances in nuclear capability, missile capability, and air power. The military budget has continued its double-digit growth, though there have been exceptions in some years, and in addition to increasing the military capabilities of the PLA, this could also intensify its assertive posture. That concern is expected to continue growing in the time ahead.

Japan has responded to such concerns in the new National Defense Program Guidelines, formulated in December 2010, that invoke measures for the adoption of a dynamic defense capability. As this indicates, Japan must deal with the situation through its own efforts while also seeking to contend with the issue through cooperation and burden sharing with the US, its only ally. The creation of management mechanisms in the event of a crisis will also be necessary in order to reinforce deterrent readiness.

In that sense, security cooperation relationships with countries in the Asia-Pacific region that are allies of the US, such as, for instance, strengthening Japan-Australia cooperation, cannot be expected to contribute directly to deterrent readiness. This is where soft balancing and institutional balancing reach their limits, and it is the reason that Japan's own efforts toward deterrence as well as strengthening of the Japan-US alliance are so important.

Strategy in Practice

At this year’s EAS, President Obama and many leaders picked up on the theme of maritime security and, in addition to a confirmation of international law and peaceful resolution in the declaration, the chairman’s statement noted the possibility of expanding the ASEAN maritime forum with wider membership. [5] It is also worth noting that Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta proposed in October 2011 that the ADMM+8 be held annually, rather than every three years as it is now. As China’s influence expands, the role of regional institutions centered on ASEAN is being underscored once again as venues for achieving a balance between the United States and China. It is yet to be seen whether a consensus can be achieved with substantial implementation. Japan has been active in this region for a long time as the provider of public goods and supporter of regional institutions. Japan’s integration strategy toward China would be based on this foundation.

Non-allied security cooperation is widely seen in the Asia-Pacific today. Fearing the loss of their autonomy and not being willing to accept the costs that would be incurred by strengthening ties to one great power or the other, small and medium-sized states have also increased their security cooperation. The primary goal is to address security challenges, but such cooperation is also intended in part to balance relations with the great powers, as appropriate.

The expansion of China’s military prowess and increasing friction with small and medium-sized states have encouraged the latter to acquire military capabilities of their own. In addition, an increasing number of small and medium-sized states are trying to strengthen their ties to the United States, in part as a way to ensure a countervailing political influence.

Relations between the United States and non-allied small and medium-sized states, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, are being strengthened through exchanges of visits by high government officials and the issuance of joint statements, enhanced staff-level exchanges, visits to military vessels and participation in military reviews, humanitarian missions, provision of training and technology related to facilities and equipment, and other types of training. Japan and Australia, too, have enhanced their efforts for better governance and capacity building for Asia-Pacific nations. [6] The Japanese approach has been influenced by the change of political leaders, but its strategic priority toward the Asia-Pacific has generally been upgraded in the last decade, and a soft-balancing strategy has emerged.

To deter and respond to security challenges from China, the hub-and-spoke alliance system, along with forward deployment, have formed the nucleus of the Asia strategy of the US, Japan, and their allies. Over the past several years as well, there has been a notable strengthening of US-Japan, US-Australia, and US–South Korea relations. In June 2011 the US and Japanese governments expanded their Common Strategic Objectives, incorporating many items on the agenda that can be interpreted as reflecting a mindfulness of China. [7]

Similarly, at the 2011 Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) that brought together the foreign affairs and defense officials from the two countries, there were a number of items of the agenda that seemed to be aimed at China, such as cooperation on cyber security, renewed deliberations on the increased deployment of US military and related facilities to Australia, and the use of military force in the South China Sea. [8] President Obama’s visit to Canberra also confirmed this trend with a new plan of rotating US Marines on Australian soil. In US–South Korea relations, the emergence of a conservative administration and the escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula in 2010 provided incentive to strengthen ties. China’s response after the sinking of the South Korean naval vessel, the Cheonan , hardened popular opinion in South Korea toward China.

Security cooperation among those US allies that form the “spokes” has also been evident in recent years, creating what might be called an alliance web. The key motivation of US allies lies in their intention to secure US commitment to the Asia-Pacific in the era of financial drought among the developed economies, and, in parallel, the US has sought to moderate its share of the security burden.

The concept of dynamic defense capability, which was adopted in the 2010 National Defense Guideline of Japan, aims to utilize the country’s limited resources with more operations. Needless to say, it is most important for Japan to coordinate with the US on deterrence and response, and the meaning of unilateral preparations by Japan’s own effort will also increase in some scenarios. [9]

Conclusion

The shape of the regional order will undoubtedly be greatly affected by cooperation and conflict in US-China relations. If we examine whether soft balancing by small and medium-sized states is bringing about any substantive change in the behavior of China and the United States, we find it remains limited at best. And it would be difficult to say that the institutions that both the United States and China have joined have to date contributed to the kind of stability in US-China relations that the regional order requires. Rather traditional problems still exist in the latter: there is little will on the part of either country to move ahead with substantive debate in institutions that the other belongs to.

The goals of the United States include confidence building with China, the formation of crisis-management mechanisms, the deterrence of China’s territorial expansionism, open access to global commons, and the recognition of America’s position in the Asia-Pacific region, while China is seeking to attenuate the influence of the United States and its alliance network, secure energy resources, and expand its influence over small and medium-sized states. By first reaching and complying with agreements in areas where agreement is feasible, eventually sharing a common understanding on the division of power, and then expanding the scope of their agreements, the United States and China could ultimately advance the stability and integration of the region.

What does this mean for the US-Japan relationship? Firstly, Japan should work along with US efforts for networking alliance and non-allied cooperation in order to sustain its commitment to the Asia-Pacific in the era of fiscal austerity. Japan could relocate more diplomatic and military resources and attention to the region. At the same time, as discussed throughout this paper, Japan should recognize the concerns for autonomy among Asian states. Secondly, Japan has the responsibility for community building through bilateral and multilateral inclusive mechanisms with China. To drag the region into a rivalry should be avoided, and Japan should endeavor to encourage rule and order creation to reflect the new balance of power. Thirdly, to avoid a situation in which solely the US and China deepen the collaboration at the sacrifice of the interests of middle and smaller powers, Japan should keep its leading roles in the regional order and also enhance bilateral and trilateral dialogue with the US and China for the sharing of vision for the order.

[1] Barack Obama, Remarks to Australian Parliament, Canberra: Parliamentary House, 17 th of November, 2011.

[2] Hillary Rodham Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy , November 2011. Hillary Rodham Clinton, Remarks on America’s Pacific Century, Honolulu: East West Center, 10 th of November, 2011.

[3] International Institute of Strategic Studies, Strategic Survey 2011 , NY: Routledge, 2011, p. 137.

[4] This section is from Ken Jimbo, Ryo Sahashi, Sugio Takahashi, Yasuyo Sakata, Takeshi Yuzawa and Masayuki Masuda, Japan’s Security Strategy toward China (Tokyo Foundation, 2011).

[5] Chairman’s Statement of the 6th East Asia Summit, Bali, 19th of November, 2011.

[6] John Bradford, “The Maritime Strategy of the United States: Implications for Indo-Pacific Sea Lanes,” Contemporary Southeast Asia , vol.33, no.2 (2011).

[7] Ryo Sahashi, "New Common Strategic Objectives for the US-Japan Alliance: Continuing Quiet Transformation," Asia Pacific Bulletin (Honolulu and Washington DC: East West Center), no. 125, July 25, 2011.

[8] “Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2011 Joint Communiqué,” September 15, 2011. Barack Obama and Julia Gillard, “Remarks in Joint Press Conference,” Canberra: Parliamentary House, November 16, 2011.

[9] Satoru Mori, Ryo Sahashi, Shoichi Itoh, Tetsuo Kotani and Yoshihiro Yasaki, Japan as a Rule Promoting Power (Sasakawa Peace Foundation, 2011.)