- Article

- Japanese Politics

Rage in the West, Apathy in Japan: Reflections on the Upper House Election

July 21, 2016

In the wake of the July 10 House of Councillors election, political analyst Katsuyuki Yakushiji contrasts the inertia and resignation of Japanese voters with the tide of populist rage that has led to Brexit in Britain and the rise of Donald Trump in the United States.

* * *

The July 10 House of Councillors election has come and gone, leaving scarcely a ripple in its wake. The election campaign inspired little excitement or enthusiasm, and the ruling coalition’s widely predicted victory left the parliamentary balance of power basically unchanged. After four straight electoral triumphs since 2012 (two in the House of Representatives and two in the House of Councillors), the Liberal Democratic Party?Komeito coalition seems securely ensconced at the helm.

In the midst of an uneventful national election came the stunning news that the British people had voted to leave the European Union, as nationalist, anti-immigrant sentiment carried the day. The US presidential race also continued to grab headlines, most of them concerning Donald Trump and his inflammatory, anti-establishment rhetoric. In both countries, a middle-class backlash against the political and economic elites had upset all the pundits’ predictions. In Japan, meanwhile, it was business as usual.

Make no mistake, Japan has serious problems of its own, and everyone knows it. It is saddled with public debt in excess of ¥1,000 trillion—the largest of any country in the world—a rapidly aging population, and a social security system that will inevitably bankrupt the government if not reformed. Among the nation’s younger workers, income equality is a serious and mounting problem. Nonetheless, Japanese voters—in stark contrast to their American and British counterparts—have quietly opted to support the status quo. How can we account for this contrast?

Understanding the Upper House Election

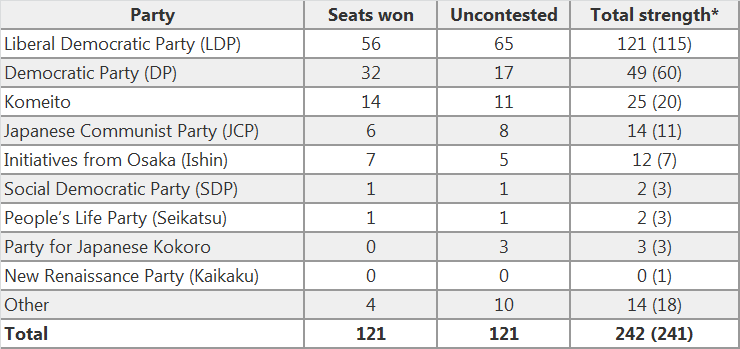

The House of Councillors, or upper house, has 242 members. National elections are held every three years to select half of those members for a six-year term. Unlike polls for the more powerful House of Representatives, upper house elections do not lead directly to a change of government; instead they are treated as an opportunity for an interim assessment of the government in power.

In this last election, the ruling coalition won 70 out of 121 contested seats, for a gain of 10, with 56 going to the LDP and 14 to its junior coalition partner, Komeito. This gave the ruling bloc 146 of the 242 seats in the upper house and left the Democratic Party (Minshinto)—the nation’s second-largest party and number-one opposition force—with only 49, a loss of 11. The results of the nationwide proportional-representation vote were particularly discouraging for the DP, which received a mere 11.8 million votes, as compared with 20.1 million for the LDP.

Upper House Election Results

This may sound like a ringing endorsement of the government's policies, but voter turnout suggests otherwise. Amid a long-term decline in voter participation, particularly in upper house elections, the turnout for the July 10 poll was 54.7%, the fourth-lowest of the post?World War II era. Around the nation the predominant mood was one of apathy and resignation.

But perhaps this is understandable, given the choice facing Japanese voters as they went to the polls.

Lackluster Opposition

The ruling LDP and Komeito decided to make the economy the focus of their electioneering, emphasizing progress made under the Abenomics policies of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Of course, the success of these policies is open to debate. While employment and wages have risen slightly since Abe took office, economic growth remains negligible, and the key objective of halting deflation has yet to be achieved. The government continues to rely on fiscal expansion to keep the economy afloat, despite Japan’s enormous public debt. Regulatory and other structural reforms needed for sustained growth—the vital third “arrow” of Abenomics—have yet to be seriously addressed.

On the eve of the election, with economic growth stalled, the government announced plans to delay a scheduled hike in the consumption tax. The ruling parties also promised voters yet another emergency stimulus package in the fall (without specifying how this was to be financed). In short, the parties in power are using unsustainable fiscal outlays to pacify vested interests and reassure elderly voters, who have a large impact on election results.

Of course, many Japanese voters regard these policies with skepticism. But the opposition failed to galvanize their support. One major problem was its election strategy. Fearing an LDP sweep in the 32 districts that had only one seat up for election, four ideologically diverse parties chose to cooperate, fielding one candidate among them in each of those districts. In a narrow sense, the strategy seems to have worked, since 11 of those candidates were elected. But the net result was a loss of seats, particularly by the DP. Voters were understandably suspicious of a “united front” encompassing the most conservative wing of the DP at one end of the spectrum and the Japanese Communist Party at the other. They saw it for the cynical expedient that it was.

In terms of message, the DP and its allies opted to focus on upholding the war-renouncing Constitution, targeting one of Abe’s obvious vulnerabilities. It is true that the Abe cabinet drew intense criticism for pushing through legislation that opened the door to Japan’s limited participation in collective defense, and it is also true that many voters oppose amending the Constitution. But these are abstract issues compared with the languishing economy. The opposition was unwilling to challenge Abe’s postponement of the tax increase, and it had nothing to offer as an alternative to Abenomics.

Faced with such a choice, Japanese voters either stayed home or took the safe route and voted to maintain the status quo. The disillusionment and apathy surrounding the election were almost palpable.

Where Are the Firebrands?

The erosion of the middle class is progressing in Japan as it is in other countries. The situation may not be as dire as in the United States or Britain, but bottom-line-oriented corporate reforms have led to a sharp increase in the number of part-time, temporary, and other “nonregular” employees; in 2015, they constituted more than 40% of all workers in Japan, according to government figures. As a result, income inequality is on the rise, and more people than ever are worried about their financial future. Yet on the eve of a national election that could have altered the course of national policy, the mood was one of quiet resignation. There were no demonstrations and no large political rallies of the sort seen in Britain and the United States.

One reason for this mood is doubtless the quality and character of our politicians. These days one rarely sees the sort of political firebrand who can tap into popular discontent and galvanize people to action, such as Trump in the United States and Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage in Britain. Of course, we can do without rabble-rousers who stir up fear and anger while offering only irresponsible and unrealistic solutions. But charismatic, inspiring politicians serve an important purpose by motivating and mobilizing voters. Among Japan’s national parties, no one since Prime Minister Jun’ichiro Koizumi has demonstrated the ability to tap into dissatisfaction with the status quo and rise above the ordinary. Perhaps the current environment is simply not conducive to that political style.

Part of the problem, however, is the general reluctance of our politicians, whether in the ruling coalition or the opposition camp, to take aim at Japan’s structural problems. After all, if they were to confront the fiscal crisis head-on, they would be obliged to call for higher taxes across the board and propose budget cuts that could impact influential blocs of voters. This is not considered the best way to win elections. For now, the safest strategy is to skirt the issue of fiscal sustainability and promise new benefits without identifying new sources of funding, on the pretense that it is possible to get something for nothing. At some level, most Japanese voters realize that this is a pyramid scheme that will cost Japan’s young people and future generations dearly. But they are too cynical about politicians and the political process in general to stage an electoral revolt.

Looking Ahead

What is next for the Abe cabinet, now that the LDP and its allies have bolstered their Diet majority? The media have made much of the fact that those who favor revising Japan’s postwar Constitution (including some in the opposition) now occupy more than two-thirds of the seats in both houses of the Diet—the threshold for initiating constitutional amendments. The LDP earlier released a hawkish draft of an amended Constitution that eschews Article 9’s “renunciation of war” in favor of the heading “national defense” and renames Japan’s Self-Defense Forces the National Defense Force. With a pro-revision supermajority in both houses, upholders of the current pacifist Constitution are getting worried.

But Prime Minister Abe seems to realize that economic recovery is a far more pressing issue than constitutional revision. Even the Bank of Japan’s radical negative interest rate policy has failed to resuscitate the economy, and now the Brexit vote and China’s economic slowdown are further clouding the outlook. The future of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Abe has called a key to sustained growth, is also in doubt. Although American and Japanese negotiators reached an agreement on the free-trade framework early this year, it is by no means clear that the US Congress will approve it. Faced with such economic challenges and uncertainties, it is hard to imagine where Abe will find the time and political energy to embark on such a controversial undertaking as amendment of the Constitution.

In fact, at a press conference on July 11, immediately following the election, the prime minister focused squarely on the economy, announcing that he had instructed his cabinet to prepare a new stimulus package. The government has pledged bold investment in public works, including infrastructure to support agricultural exports, accelerated construction of a maglev railway line, and expansion of the nation’s Shinkansen bullet train network—a laundry list of ambitious construction projects recalling the bygone days of rapid economic growth. It is also promising to spend more on services for the elderly and scholarships for college students.

The LDP’s parliamentary position may look unassailable, but most policymakers understand how quickly voters can turn on their leaders when their livelihood is threatened. In this respect, Japanese voters are no more stoical than their American or British counterparts. They may seem docile now, but their apathy will surely to turn to rage if and when the bottom falls out of the Japanese economy.