- Article

- Political Institutions

Political Reform of the Japanese System of Government (Symposium Report 2)

January 29, 2009

In Japan's parliamentary cabinet system, the expected relationship between the ruling political parties and the cabinet is distorted, as are the roles played by politicians and bureaucrats, and the parliament itself is nearly dysfunctional. This analysis of Japanese government today includes recommendations to improve the tenor of the nation's politics and politicians. (This article was distributed at the "Comparison of Parliamentary Politics in Japan and Britain" Symposium to enhance participants' understanding of Japanese government.)

Click here for the symposium program and list of panelists; click here for the summary of the keynote lecture by Lord Cunningham of Felling.

Starting Point: Cabinet's or Ministry's Prerogative?

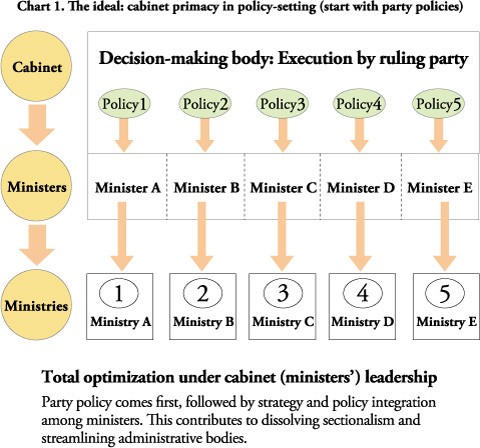

Japan uses the parliamentary cabinet system. This system is broadly understood as follows: a political party (or coalition of political parties) that has won an election and dominates a parliament organizes a cabinet by appointing the ministers to fulfill its campaign pledges, and the ministers use bureaucrats as staff to conduct their policy. Chart 1 below illustrates this process.

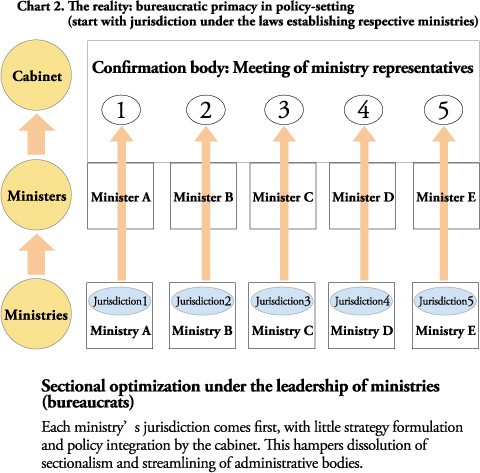

The reality in Japan, however, is very different from that supposed process, as seen in chart 2:

The procedural order of Chart 2 is the reverse of that of Chart 1. In Japan, ministries with their jurisdictions stipulated in the establishment laws and bureaucrats in their own right wield policy primacy, and ministers parachute into this existing structure. The fact that most ministers just read speeches prepared by bureaucrats at an inaugural press conference demonstrates this well. The ministers transform themselves into representatives of their ministries' interests and positions, regardless of their opinions as Diet members prior to assuming their portfolios. The cabinet actually is the aggregation of such ministers.

This format explains many problematic aspects of Japanese politics and administration. The first one is bureaucracy, which is clearly shown in chart 2.

The next problem is administration hampered by sectionalism. The process in Chart 1 would dissolve sectionalism through ministerial coordination under the direction of the prime minister, regardless of each ministry's jurisdiction. The reality, however, is shown in chart 2, where meaningful coordination at the ministerial level is difficult to realize.

The format in Chart 2 also clearly shows the difficulties Japanese governments have in effecting appropriate change in policies and systems and in responding to changing situations swiftly: ministries are the primary actors, and they often put too much emphasis on past records. It also explains why ministers sometimes lack sufficient insight and knowledge in their policy domain and why they are replaced frequently in a process like periodic personnel transfers in a company. Given this reality, it is no wonder that in the past political parties have fought elections with no concrete platform.

Dual Structure of Cabinet and Ruling Party

Another abnormality in the Japanese parliamentary cabinet system is the relationship between political parties and the cabinet.

A cabinet should be a body that executes and realizes the policy of a political party that won the support of a majority of voters. In Japan, however, the policy of a cabinet often contradicts that of the ruling party. The postal privatization by the Junichiro Koizumi cabinet was a typical example.

Also, a prime minister or minister in charge often states that he or she will decide policy later since study is still underway in the ruling parties. This is because of the dual cabinet-party power structure. Japanese political parties have a department for policy, such as the main ruling Liberal Democratic Party's Policy Research Council, and that department checks the government's bills and other policy measures. This organ sometimes issues a proposal that is different from the government's policy. The submission of a government bill requires prior approval by the party's General Affairs Council after being cleared by the policy council, and the bill may be modified drastically or even rejected in this process. The heads of the two councils, along with the Secretary General, constitute the troika of the LDP-the three top party officials, posts that are filled by influential politicians. They have more power and a louder voice than the ministers who are nominally the policy chiefs of the government. As a result, a party's voice often takes precedence over a minister's policy based on the proposals of his or her ministry or advisory panel when they conflict with each other.

As bureaucrats are well aware of this political structure, they go to seek the understanding of powerful party members, including the troika and Diet members affiliated with the relevant committee under the Policy Research Council of the LDP, rather than supporting their minister and expecting the cabinet's control over the ruling parties. The ideal cabinet, which wields the ruling parties' political power to realize the party platform, is out of the picture, and policy is decided by bureaucrats and influential party persons.

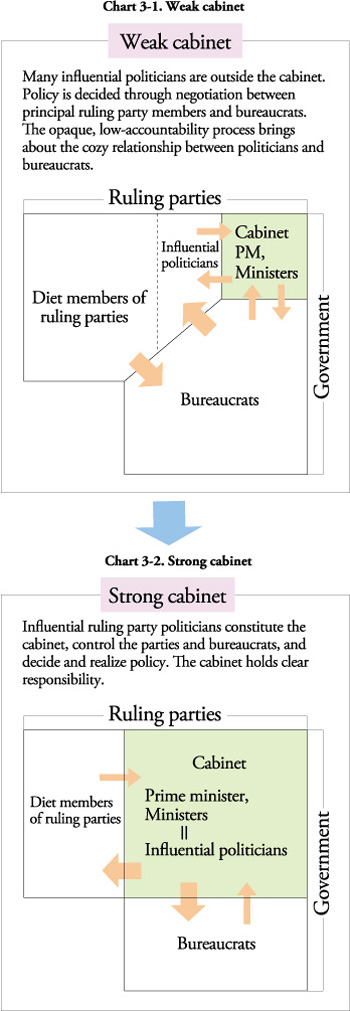

These decision-making mechanisms are illustrated by the charts below.

Chart 3-1 illustrates a weak cabinet, with influential politicians of a party outside the cabinet and bureaucrats' close relationships with party Diet members. Chart 3-2, meanwhile, depicts a situation in which bureaucrats work only as staff to ministers.

These facts lead us to the problems in the Japanese parliamentary cabinet system: because of the dual power structure of the ruling parties, there is a lack of transparency and accountability in the policy-making process; individual or personal interests of political parties and politicians are greatly reflected in policy; the dual structure combined with the unusual parliamentary cabinet system of Japan explained above makes bureaucrats "central players" in the policy-making process through explanation and negotiation, resulting in bureaucrats' effective control over political decisions; and politicians, on the other hand, are eager to represent and incorporate individual or personal interests among their constituents in policy. These phenomena are chicken and the egg to one another. The negative spiral of a weak cabinet, powerless cabinet ministers, and incompetent politicians who can still get a portfolio has been degrading the cabinet, politics, and all politicians.

What should be done to improve the quality of politics and politicians by dissolving the deviation from the original parliamentary cabinet system and the various problems resulting from it, as explained above?

I think that a clearer, more transparent, more accountable approach to decision-making is crucial at each stage of political process (policy formation, election, cabinet formation, and policy implementation) to realize political reform. My concrete proposals for that are as follows. They center on codes of conduct for political parties and politicians.

Policy Formation

- Establish a clear policy formation process within a political party

- Create a common format for the party platform in an election; deregulate distribution and publicity of the party platform

Elections

- Define selection criteria for party candidates and open the selection process to the public

Cabinet and political party management

- Define selection criteria for ministers

- Clarify the authority and responsibility of intra-party organs, such as the Policy Research Council and the General Affairs Council; require the chiefs of the organs to join the cabinet

Policy implementation and role of bureaucrats

- Restrict bureaucrats' contact with Diet members other than their minister and their activities with stakeholders outside their ministry, including explanation and negotiation

- Abolish the laws for the establishment of respective ministries

- Set rules for political appointment of government positions

- Require political parties to prepare and make public reports on their activities and finances; consolidate and publicize financial reports on more than one of the channels for political fund management, and mandate external audits

- Oblige political parties to hold general meetings of their constituencies, in addition to the rules mentioned in (8) above

For Further Information

The "Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet" website provides information on the governmental framework of Japan, including sections titled "Constitution and Government of Japan" and "Cabinet System of Japan."

1 Japan's bureaucrats (editor's note)

Japan's bureaucrats wield considerable technical expertise, allowing them to play a major role in public policy formulation. The bureaucracy has been responsible for the drafting of some 90% of all legislation passed by the Diet since 1955. The system provides for powerful extralegislative instruments that can supplement and even bypass the legislative process: on the bureaucratic side, there are ministerial ordinances, and the cabinet can issue cabinet orders. Each ministry has deliberative councils composed of representatives of private interest groups and individual experts to provide advice on matters under ministry jurisdiction. In theory these councils provide with the bureaucracy with outside expertise, but in general it is the ministerial staff that sets and oversees the investigative agenda and produces the councils' final reports.