- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Thoughts on the Principles and Practice of CSR Management

June 13, 2019

Summoning years of experience in socially responsible business management, the former president of Fuji Xerox and current representative director of Global Compact Network Japan provides insights and tips for putting CSR and the SDGs into practice in a competitive business environment.

* * *

As a senior executive, I spent many years practicing corporate social responsibility while working hard to maintain strong business performance and growth in a highly competitive environment. As president of Fuji Xerox, I signed the United Nations Global Compact in 2002, and I was a member of the Global Compact Board for a decade, beginning in 2008. I currently serve as representative director of Global Compact Network Japan while continuing to engage in corporate management as an external director. My understanding of CSR and CSR management is rooted in this experience.

In recent years, the media has helped disseminate various buzzwords pertaining to corporate social responsibility, from CSR and CSV to ESG and the SDGs, and such talk has become common in Japanese business circles. But it can be daunting and bewildering to contemplate the actual integration of the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) or ESG (environmental, social, and governance) criteria into business management. Most business leaders—recalling their own experience with disasters and extreme weather events—would readily agree that the sustained health of their business depends on that of the social infrastructure and environment. Yet to many, beset by the pressures of market competition, it doubtless seems much easier to leave larger concerns about the environment and society to the public sector.

The fact is, however, that companies have a responsibility, both to their current stakeholders and to future generations, to build a sustainable business community and global society. To do so, they need to grasp the basic principles and mechanisms of CSR and incorporate them into real-world business management. In the following, I would like to share my thoughts on effective CSR management, illustrated with specific examples drawn from my own experience.

Toward a Basic Understanding of CSR

If asked, most Japanese business leaders will agree that CSR is a very important component of business management. Yet CSR officers and consultants are always complaining that corporate executives are missing the point. It seems to me that different people mean very different things when they talk about CSR management. In the absence of a shared understanding of the core meaning of CSR, the rapid appearance of new concepts—each with its own set of initials (SDGs, ESG, CSV, and so forth)—has inevitably led to a certain amount of confusion in the business community.

Here are a few of the most common perceptions (and misconceptions) one encounters regarding CSR.

- A company’s primary responsibility toward society consists in supplying the world with useful products and services and distributing the profits to shareholders. (The “shareholders first” school)

- A company fulfills its social responsibility by paying taxes and providing employees with jobs and compensation; environmental and social problems are the responsibility of the public sector. (The “tragedy of the commons” school)

- The responsibility of a corporation is to comply with governmental and industry regulations and standards. (The compliance and governance school)

- CSR means demonstrating good citizenship by contributing volunteers, money, or products to charity and worthy causes. (The philanthropic school; a subcategory, the “school of indulgences,” hopes to earn forgiveness for any misconduct through its good deeds.)

- A company must monitor its domestic production sites closely—just as a hotel would its own kitchen—but has no responsibility for human-rights or labor abuses among its overseas suppliers. (The homebody school)

- CSR is mainly about improving corporate image; therefore, a company should strive to raise its profile through distinctive CSR programs that have little relevance to its core business operations. (The showcase school)

I have a somewhat different take on CSR. Integration of CSR into management occurs through the processes of capital raising, business operations, and value delivery (see Figure 1). My view is that CSR encompasses a company’s responsibilities to all its stakeholders in all of its management processes, including those of its value chain. In its conduct of all such processes, a company has a responsibility (1) not to create problems, (2) to address existing or potential problems, and (3) to create new value. However, this approach requires a fundamental shift in thinking regarding a business’s raison d’etre. I discuss the various categories of CSR activity, as well as corporate philanthropy, in greater detail below.

Figure 1. Management Processes and Stakeholders

Source: Created by the author.

The Rise of CSR

Three decades have elapsed since the fall of the Berlin Wall, which heralded the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in 1991. In the 1990s, with the Iron Curtain gone, global capitalism spread quickly. The transnational business activities of big corporations fostered the rapid growth of markets, but they also fueled serious problems, including child labor and destruction of the environment. The concept of CSR was a reaction to such dark sides of globalization.

I would trace the inception of this movement to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s address to the World Economic Forum in Davos in 1999, when he challenged the leaders of business to join with the United Nations in “a global compact of shared values and principles, which will give a human face to the global market.” The following year, 2000, saw the adoption of the UN Global Compact, a platform for CSR management. Under this voluntary initiative, participating companies pledge to work with the United Nations to observe 10 management principles under the four headings of human rights, labor, environment, and anticorruption.

The year 2000 also saw the adoption of the UN Millennium Development Goals, which spelled out social and environmental outcomes toward which the international community agreed to strive, in large part by practicing the code of corporate conduct set forth in the UN Global Compact. Then in 2015, the target year for the MDGs, the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, embracing 169 targets for the achievement of 17 Sustainable Development Goals spanning the developing and developed world. Today the SDGs are a powerful driver for corporate action to address the biggest issues facing humanity.

As I see it, CSR as a global movement began in 2000 with the UN Global Compact and the MDGs. They spelled out a basic code of conduct, identified a set of goals for dealing with global issues, and called on the heads of industry to exercise strong leadership to ensure that their companies met their responsibility to society.

On the other hand, 2003 is often identified as “Year One” of the CSR era in Japan. Of course, Japan has its own tradition of business ethics called sanpo-yoshi (“good for three parties,” that is, sellers, buyers, and society) dating from the Edo period (1603–1868). But it was in 2003 that the international concept of CSR began to take hold in Japan, as evidenced by the appearance of corporate units and departments expressly dedicated to CSR. Another important milestone that year was the release by the Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives) of its fifteenth Corporate White Paper, titled “Market Evolution and CSR Management.” Here, the Keizai Doyukai argued that it was time to shift from a market governed by free competition to one governed by socially responsible business management. It called for “triple bottom line” (social, environmental, and financial) accounting to achieve such a shift.

CSR and Strategic Management

Today, mainstream thinking about CSR emphasizes the integration of sustainability principles into strategic management. But how does this work in practice?

The primary mechanism by which sustainability enters into management via the capital-raising process is ESG investing, a much-discussed trend in the investment community. In ESG investing, companies are screened for sustainability on the basis of environmental, social, and governance criteria. While companies incorporate CSR by following the UN Global Compact’s guidelines in the four areas of human rights, labor, environment, and anti-corruption, investors rate those efforts within the ESG framework. Engagement between management and shareholders provides a direct link between sustainable investing and corporate management.

While current trends emphasize integration of CSR into these core management processes, CSR can also take the form of corporate philanthropy, that is, charitable donations or participation in volunteer activities. Such programs are originally rooted in altruistic rather than strategic considerations, but they can also work to enhance corporate value. They do this primarily by educating and motivating employees, fostering public trust, and building external networks, thus building the organization’s capacity to do business. Accordingly, when planning a corporate philanthropy program from a strategic standpoint, one needs to consider how it will contribute to various components of corporate capacity.

Integration of CSR can and should involve all three basic management processes: capital raising (investment), business operations, and value delivery. Within this general framework, CSR plays various strategic roles, which can usefully be divided into the categories of capacity building, defensive strategy, and offensive strategy.

In the context of business operations, CSR involves upholding the principles of the UN Global Compact in one’s own business activities and those of one’s value chain. The Global Compact groups these principles under the broad areas of human rights, labor, environment, and anticorruption, but in practice, companies usually identify more specific issues relevant to their own business from within those broad domains. Measures to address those issues in an appropriate manner serve an important defensive function by minimizing the risks associated with noncompliance, as well as the risk of damage to brand value and public backlash, including consumer boycotts. With this in mind, companies have an important strategic interest in instituting “defensive” CSR systems and mechanisms to avoid or minimize risk, before and after the fact. In the realm of human rights, these would include due diligence, employee training, and a basic human-rights policy or code of conduct. In some cases, CSR measures of this sort could play a role in a company’s offensive strategy, as by improving brand image, but the central role of CSR in business operations is a defensive one.

The role of CSR in value delivery is self-apparent if we interpret “value” holistically, as encompassing not only the functional and economic value of products and services but also the social value delivered by pursuing such Sustainable Development Goals as no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, and climate action. In effect, the SDGs represent the world’s market needs. A company that can build a business model that maintains profitability while meeting those needs will have a competitive advantage. This is CSR as an offensive business strategy.

The United Nations estimates that the SDGs present some $12 trillion in new market opportunities: $1.8 trillion in the health and well-being sector, $2.3 trillion in food and agriculture, $3.7 trillion in cities and transportation, and $4.3 trillion in energy and materials. This could be a huge boon for Japanese industry, which is facing the constraints of a mature domestic market and a shrinking, aging population. A sound offensive strategy will be essential to sustained competitiveness and business growth in the years ahead.

The products and services brought to market through CSR management can also be applied to mitigate problems facing the developing world. In this way, businesses can develop new markets while helping to realize the vision of “leaving no one behind,” a guiding principle of the 2030 Agenda. Here and elsewhere, the SDGs hold the promise of new markets in which small, mid-sized, and regional companies can compete on a relatively even playing field with big business, leveraging innovative products and business models.

Going on the Offensive

Any company hoping to branch out from its current operations and embark on a business offensive oriented to social solutions and the SDGs needs to address three key challenges.

- The first is investor valuation. Unless investors support the program, share prices will fall, and the business will lose value. Can you secure the support of investors?

- The second is recovery of value-integration costs. The integration of social value and economic value generally entails new investment and other expenditures, adding to unit costs. Can you develop an “integration model” for recovering those costs?

- The third is the deployment of a sustainable business model. When venturing into a new market, one needs a business model that is structurally sustainable. Do you have a viable approach?

Business experts are still debating the best way to tackle these key challenges, but in the following I tentatively offer my own thoughts on the subject.

Investor valuation

In the past few years, the Financial Services Agency has published two major sets of guidelines for sustainable business management. The first, Japan’s Stewardship Code, is oriented to institutional investors, while the second, the Corporate Governance Code, is targeted to Japanese businesses themselves. Both promote the application of ESG (economic, social, and governance) criteria for the realization of sustainable management.

The Financial Services Agency’s new emphasis on ESG attempts to counter the short-term orientation of shareholders, a welcome development for companies interested in taking a long-range approach to value in order to pursue the SDGs and address social issues. Even so, investors tend to make their decisions with financial results in mind. To win over investors, a company must have a sound medium- to long-term strategy and a concrete plan for new business development, all consistent with a clear and principled management philosophy. Armed with these concepts and blueprints, it must actively engage with investors to win them over to its vision of sustainable management. We need to create a new paradigm of joint valuation by managers and investors, leading to ever-higher corporate value.

Recovery of value integration costs

Businesses must compete in the market. They must continue to attract customers and post profits even while contributing solutions to society’s problems. Sustainable management means creating “integrated value” via products that offer social as well as traditional economic value, and this integration entails investment and added expenses. As a business, one must recover those costs. If the revenue from the integration of value exceeds the costs, then the business is viable. A good example is the success of hybrid vehicles, which the market embraced for their social value. Figure 2 illustrates the process schematically.

Figure 2. Integration of Economic and Social Value

Source: Created by the author.

Business-model deployment

Assuming that one finds a way of recovering the added costs of integration, one must still come up with a business model that supports the business’s processes and profit structure in a sustainable manner. To take an extreme example, electric vehicles required new infrastructure, such as charging stations. In this way, business models in the automotive industry depend on a very extensive value network. This is much less true of office equipment.

In the following, I look at Fuji Xerox’s development of a business model for delivering integrated value in the office equipment industry.

Fuji Xerox’s Value Integration

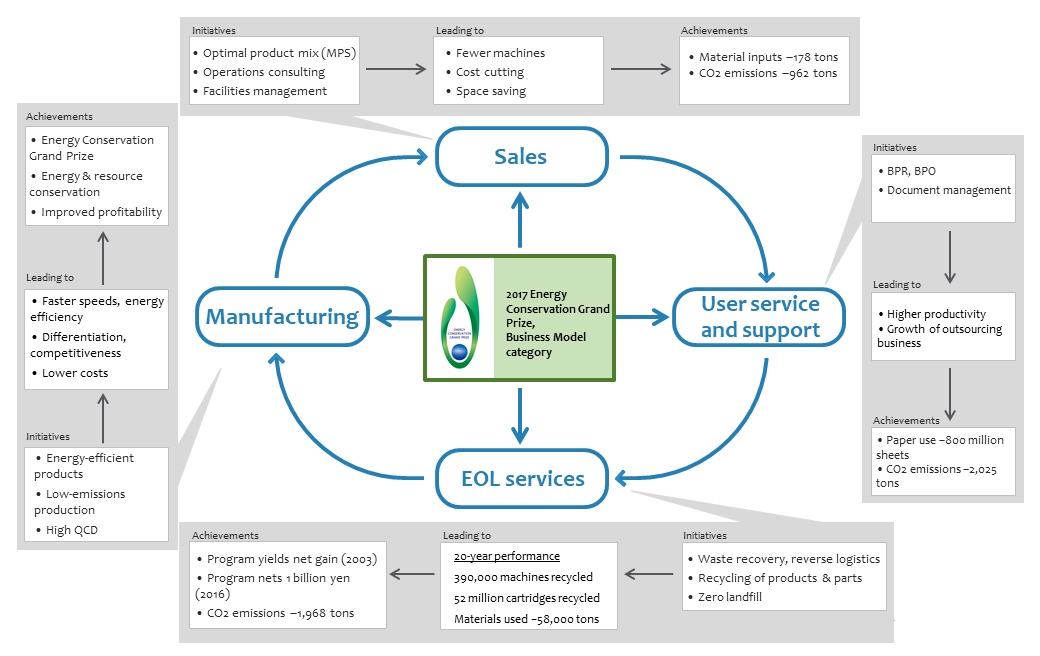

In the office equipment industry, the typical product life cycle can be broken down into four stages: manufacturing, sales, user service, and end of life (EOL) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Life Cycle of Office Equipment

Source: Created by the author.

From its beginnings in 1962 until the 1980s, Fuji Xerox (FX) pursued a business model that relied heavily on revenue from after-sales service and sales of supplies to the offices that purchased or leased its copiers. In the early 1980s, well before the spread of digital technology and computer networks, the company developed a pioneering system called Star (regarded as a precursor of the Mac and Windows desktop computer systems) for creating and storing digital documents. This technology, when used in conjunction with digital networking, opened the way for document management that seamlessly integrated paper and digital documents. This “document management” technology became FX’s core technology, and the concept of “value through document management” shaped the FX’s evolving business model. With that business model, FX was able to seamlessly incorporate business-solutions services and energy efficiency, thus developing into a company that delivers integrated value.

Let us trace the development of FX’s business model in greater detail with the help of Figure 4.

Figure 4. Development of Fuji Xerox’s Integrated Business Model

Source: Created by the author.

Eco-products: The development of energy-efficient copiers resulted in reduced energy consumption and lower electricity costs. The development of compact models cut back on the use of manufacturing materials, lowered unit costs, and yielded a space-saving footprint. FX’s energy-efficient, compact machines made the business more competitive, ensuring dependable returns on investment.

Resource recycling system: FX launched its recycling program for machines and cartridges in 1995. While recycling reduced the use of materials in manufacturing, the process was complex and costly at first, and the program initially operated in the red. However, in 2003, after years of cost-cutting innovations yielding some 200 patents, the savings overtook the costs, and the program began to deliver economic as well as social value. In 2004, FX established a recycling center in Thailand, which serves as the hub of a nine-country Asian recycling system. In 2008, it established an integrated recycling system in China as well.

Facilities management: Under this business model, FX contracts with customers to fill all their office machinery needs, in most cases retaining ownership of the equipment. Equipment, including recycled machinery, is installed for optimum efficiency, helping customers realize major savings on materials, energy, and space. Initially, this led to a drop in FX equipment and supply sales, but the company made up for those losses in the form of improved customer relations and growth in revenue from office solutions.

BPO and BPR: With business process outsourcing, FX developed a business model in which it contracted with customers to fulfill all their in-house printing needs. Customers benefit from improved efficiency and reduced costs resulting from the streamlining and digitizing of these processes, while FX benefits from an important new source of business revenue. Business process re-engineering is another outsourcing business model that supports business-process reforms centered on document management. Both create integrated value by simplifying, streamlining, and speeding up business processes; cutting costs; and conserving energy and resources.

Meeting the Challenges of Sustainable Management

Looking back on my years at Fuji Xerox, I must hasten to add that this path was neither smooth nor straight.

In 2003, as president, I launched the V06 management reform program in an effort to drastically improve corporate capacity. The central aim was to boost our sales and operating margin. V06 encompassed a number of reforms, but the main thrust was a shift toward a services-based business model, something the market was already demanding. However, changing the course of our entire operations was no easy matter. I resolved to embark on a wholesale restructuring of our sales operations, which included transferring some of our sales divisions to subsidiaries. Unfortunately, middle management, which is so crucial to any such reform, was not on board. To win them over, we organized the Change Management program, dividing some 1,500 middle managers into 35 teams and holding retreats for each team over a period of eight months. I attended each of those retreats to engage in dialogue with our middle managers.

One thing I learned in the process was that top management needs to explain the business values underlying such a reform. I thus organized a task force to identify the goals of corporate capacity building. Its conclusion was that corporate capacity building is not just about boosting sales and profits. It is about creating the capacity to meet the basic social responsibility of a corporation, which is to create social, human, and economic value in an integrated manner. Integration is key, since these different value criteria tend to work at cross purposes with one another. The task force noted that the quest for integration stimulates innovation. As a prime example of this dynamic in action, it cited FX’s resource recycling system.

I decided to call the concept “corporate quality,” and in 2004, I launched a campaign under that slogan, inside and outside of the company. As president, I continued to promote V06 as an important path to corporate quality. This, in effect, was my version of CSR management.

Figure 5 summarizes our integrated-value initiatives, along with their outcomes and achievements, superimposed against the office-equipment life cycle. Here are some of the highlights in a nutshell. Through facilities management, we were able to cut material inputs by 178 tons and CO2 emissions by 962 tons annually. Thanks to business process outsourcing, paper consumption was reduced by 800 million sheets, and CO2 emissions by 2,025 tons. The company’s resource recycling system recycled 390,000 machines and 52 million cartridges over the course of two decades. In 2016, the program netted approximately ¥1 billion in profits.

Figure 5. Product Life Cycle and Integrated Value at Fuji Xerox

Source: Created by the author.

In the past, Fuji Xerox’s multifunction copiers were frequent recipients of the Energy Conservation Grand Prize administered by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. In 2017, Fuji Xerox received the METI Minister’s Prize in the Business Model category. This is eloquent testimony to the evolution of CSR management at Fuji Xerox. It also reflects progress in society’s notions of eco-friendly business, with emphasis shifting from individual products to total systems and processes. Japanese businesses are said to lag behind those of the West when it comes to capitalizing on the business opportunities of the SDGs. But it seems to me that if we have the will and the capability to deploy new business models that can deliver integrated value in this manner, we should be able to carve out our own growth opportunities, particularly by addressing social issues and needs in the developing world.

From Inside-Out to Outside-In

The examples of value integration and business-model development I have presented thus far were all extensions of FX’s core business operations. But the 2030 Agenda, with its principle of “leaving no one behind,” calls for something more. The prospects for achieving the SDGs at the global level, with no one left behind, are dim as long as companies confine their initiatives to their current comfort zone.

The SDG Compass, a guide for aligning business strategies with the SDGs (developed by the UN Global Compact in cooperation with other bodies), calls for a shift in companies’ goal-setting approach, from “inside out” to “outside in.” In addition to starting from the company’s existing businesses and business models (inside) and applying them to society’s problems, there is a need to start from the outside, meaning the issues facing humanity, and develop sustainable business models to meet those needs.

But how does one go about that? I can think of three possible approaches offhand.

One approach would be to use one’s core technologies and business model as a springboard for the development of solutions to the problems facing developing countries or depopulated regions of Japan. For example, as an extension of its existing document-centered business model, FX has partnered with other entities, including companies in the printing and publishing industries, to produce and distribute educational materials for disadvantaged schoolchildren in Asia’s developing countries. Although the program has yet to achieve commercial viability, there are high hopes for its future potential, both as a business and an effective system of education delivery in the developing world.

Another possibility is to marshal one’s internal competencies to develop a brand-new solution, with the SDGs in mind, and use that to launch a venture on a modest scale. If it succeeds, one can gradually scale it up. One example of this approach is the application of advanced computer and communications technology to support farmers in developing countries.

Finally, there is the option of participating in efforts by other business entities to solve problems in the developing world, as through mergers, acquisitions, and investment in social businesses or ventures.

There have already been positive reports from companies that have put these approaches into practice, and I am hopeful that they will generate new business opportunities while contributing to the achievement of the SDGs.

A Final Word

Businesses must grow if they are to survive over the long term, and in this age of rapid change, a company cannot grow by defensive strategies alone. They need to go on the offensive in CSR management aimed at solutions to social issues that lie outside their core business. This means adopting a perspective beyond the confines of one’s existing products, services, and business processes.

I have already discussed three key hurdles to sustainable management as an offensive business strategy. Here I would like to discuss two important psychological considerations.

The first is a mindset that views the SDGs as a business opportunity. In this context, it is instructive to compare the results of corporate surveys conducted in Japan and Europe in 2016. In the survey conducted by CSR Europe (of 10,000 companies in 41 European countries), 52% of the business leaders surveyed agreed that it was important for their company to engage in the SDGs because doing so “poses new business opportunities.” By contrast, only 37% of Japanese companies (surveyed by the Business Policy Forum, Japan) agreed with that statement. On the other hand, in a survey of Japanese companies participating in the UN Global Compact, conducted by GCNJ, a full 60% of respondents identified business opportunity as a reason to pursue the SDGs.

An information gap may be responsible for this discrepancy, as may differences in the application of ESG criteria by institutional investors and financial institutions. In any case, it seems clear that GCNJ still has much work to do.

Another point to consider is the relationship between the SDGs and business models. A survey conducted by the Japan Management Association in 2017 asked executives how many more years they expected their business model to continue functioning effectively—3 years, 5 years, or 10 years. A full 45% of respondents said 3 more years, while only 16% said 5 years, and a mere 4% gave it 10 more years. This may seem to reveal a lack of self-confidence, but it also reflects today’s widespread belief that business models do not last very long. Under the circumstances, a corporation may opt to develop a new business model or to modify and extend the current one. In either case, it is a key element of business strategy and a central challenge for business in the CSR era.

In the end, sustainable management means reaffirming the fundamental purpose of a business corporation: offering solutions to challenges facing society—in other words, customers—in exchange for payment. The SDGs constitute the definitive list of social issues as compiled and approved by the global community. By developing viable business models capable of delivering integrated value, companies can turn these challenges into business opportunities. For Japanese industry, which is widely considered “a lap behind” when it comes to seizing these opportunities, the highest priority now is to embrace the SDGs and ESG and put the principles of CSR management into practice.