Introduction

Ever since the 2002 Earth Summit in Johannesburg, sustainable development has been the topic of countless discussions and debates at the national and international levels. In Japan, 2003 is often characterized as “Year One” of the corporate social responsibility (CSR) era. Fifteen years have passed since then, and while the buzzwords have changed, the core principles of social responsibility have remained constant and have found their way into the mainstream of Japanese business management. Never has this trend been more pronounced than in 2017.

Perhaps the single biggest factor behind the heightened emphasis on CSR and sustainability was the decision by the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), announced in 2016, to consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors along with financial criteria when making investment decisions. At EY Japan, we noticed a major shift in attitudes following the GPIF’s announcement. Business executives who had previously dismissed the prominence of ESG investing—saying they had never heard an investor raise those issues—began calling it the wave of the future.

Accelerating this trend was the establishment in late 2016 of the government’s Sustainable Development Goals Promotion Headquarters, dedicated to the pursuit of the 17 goals (SDGs) embraced by the international community with the adoption of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015. Over the past year, the private sector has begun engaging actively with the government to deliver on the SDGs, and this advancement was even the central theme of the revised Charter of Corporate Behavior adopted by Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) in November 2017.

In the West, excessive focus on short-term profits has been highlighted as a major driver of unsustainable business practices. Could the influence of institutional investors and the interest in the SDGs alter that dynamic? And what do recent trends signify for the competitiveness and sustainable growth of Japanese corporations, which have long been criticized for paying too little attention to shareholders? In the following, I would like to explore ways in which the latest trends in CSR, particularly ESG investing and disclosure, are changing the rules of economic activity worldwide and discuss the implications for Japanese businesses.

CSR and the Failure of Financial Capitalism

The search is on for a new, sustainable model of capitalism. Capitalism is an economic system based on private ownership and free competition, under which the pursuit of individual and corporate profit is expected to lead ultimately to the optimal distribution of wealth throughout society, thanks to the “invisible hand” of the market mechanism. Unfortunately, instead of being optimally distributed, wealth has become ever more concentrated in recent years, as exploitative business models and the growing influence of big business in politics and government have combined to exacerbate economic inequality.

Traditionally, national governments have played an important role in the redistribution of wealth by collecting taxes from wealthy individuals and big corporations and reinvesting the revenues in social infrastructure and education. But that mechanism is breaking down. In 2010, a study by EY Japan based on World Bank data found that 43 of the world’s top 100 firms were multinational corporations. These corporations have the potential to maximize profits by procuring resources cheaply from countries or regions where lax environmental and labor regulations may exist, while reducing tax payments through the use of tax havens.

As a result, the wealth siphoned from the world is allocated among themselves. Many individual corporations operate on a scale that dwarfs some state governments (and may even underpin their national economies), but without a comparable level of responsibility and accountability to the public as a government. Businesses influence the political process through lobbying and political donations, effectively blocking any onerous regulations that might restrict them. The interests of politicians and government officials have grown increasingly entangled with those of big business.

Another factor contributing to this dysfunction is the rise of financial capitalism. In the United States, the main driver of the global economy, the financial sector has long since replaced manufacturing as the largest contributor to GDP. Manufacturing is a broad-based and diverse sector, a complex ecosystem embracing people of all educational backgrounds and skill levels. Finance is much less inclusive from the outset. Moreover, unlike manufacturing, whose products offer visible, tangible value in exchange for money, our complex financial system gives rise to information asymmetries that make it easy for a privileged few to control the flow of capital. The Enron scandal that broke in 2001 and the subprime mortgage crisis that hit Wall Street in 2008 are among the most memorable examples of this system’s failure.

Given their immense influence over the world economy, rivaling or eclipsing that of national governments, businesses are being called on to assume social responsibility commensurate with their wealth and power. This is only natural, given that society has thus far borne much of the cost of business externalities. For example, the production of consumer products—however convenient they may make our lives—often depends on materials produced through environmentally damaging mining or logging operations. Such products can also contaminate the environment after disposal. Yet in many cases, it is the victims themselves who pay for externalities in the form of damage to their health or loss of livelihood, and when governments compensate the victims or launch cleanup programs, it is the taxpayers who foot the bill. How would today’s multinational businesses fare if they were required to pay all the social costs associated with their production, distribution, and sales activities?

In the International IR Framework released in 2014, the International Integrated Reporting Council identifies six types of capital—financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural—and calls for disclosure of “the internal and external consequences (positive and negative) for [each of] the capitals as a result of an organization’s business activities and outputs,” taking into account “the extent to which effects on the capitals have been externalized (i.e., the costs or other effects on capitals that are not owned by the organization).”[1] This means not simply appending a list of environmental and social initiatives to one’s financial results but providing a complete financial accounting of the business’s external impacts—meaning its social costs as well as the value it delivers. This kind of thinking has the potential to reshape CSR management going forward, provided we understand the core purpose of disclosure and leverage it to reform management—as opposed to using the reporting framework as a template for published reports.

Delayed Development of CSR in Japan

Japan has been hit by a series of high-profile corporate scandals in recent years, some involving serious financial misconduct and accounting irregularities, others entailing falsified quality and safety data. It has emerged that a number of Japanese businesses have been cutting corners for years, despite the country’s reputation for quality and integrity. How did a situation such as this come to pass?

The same systemic issues come up time and again: Quality and governance safeguards become empty formalities in a corporate culture lacking transparency, shared ideals and goals, and a sense of individual responsibility among the top ranks of management. These are largely the same issues we see in companies that give lip service to CSR without embracing social responsibility as a core theme of corporate management. The directors may emulate the example of progressive companies in establishing a CSR department, but they give it no clear mission, substantive function, or connection with other corporate divisions, and show little interest in what it says or does.

Corporate social responsibility means exactly that, and it needs to be a central and pervasive principle of management, extending to every aspect of business operations. Yet in most Japanese companies, the purview of the CSR department is limited to matters not already under another department’s jurisdiction. Since supply-chain issues are the jurisdiction of the procurement department, labor rights and diversity the job of human resources, and corporate conduct the purview of compliance, the CSR department is put in charge of charitable programs, the only job left. This is one reason CSR has long been equated with corporate philanthropy in Japan.

When it is said that CSR goes beyond legal compliance, it is not meant that corporations should serve society through activities divorced from their business operations. Instead, it is meant that beyond their legal obligations, companies have a moral and ethical responsibility to maximize the positive impact and minimize the negative impact of their operations.

The positive impact of a business is the social value it creates. Under the classical rules of capitalism, a business that does not contribute something of value to society is eliminated from the market. A company secures the support of stakeholders through a corporate mission, explaining its raison d’être, and then delivers value through its business operations. Without support for its mission, the company cannot secure necessary resources, and without exchanging products or services of value, it cannot earn profits.

Negative impact refers to a business’s direct and indirect costs to society, most notably in relation to the environment and human rights. This means that companies bear responsibility not only for their own misconduct but also for facilitating, condoning, or simply permitting misconduct (such as forced labor) by others in the supply chain.

Many in the Japanese community have struggled to grasp the concept of corporate social responsibility as something extending beyond legal compliance. Japan, as a country, was not founded on a set of principles, and the Japanese people have tended instinctively to align their behavior with that of those around them. The ability to steer a judicious and ultimately advantageous course by “sensing which way the wind is blowing” is regarded as a basic life skill in Japanese society. The same applies to corporations. Japanese companies set their policies in large part by looking at what other Japanese companies are doing.

Respect for authority is another important feature of Japanese culture and society. For the Japanese, maintaining a smooth, stable, and mutually profitable relationship with authority is a key survival strategy. Orders from above—whether from the government, a client, or a supervisor—are not to be questioned. It follows that individuals are less inclined to act on their own ethical judgment. But CSR calls for such judgment. As long as businesses rely on the letter of the law and the behavior of others to determine right and wrong, they will never develop social responsibility in the true sense of the term. Japanese corporations must begin to think and act for themselves.

Change and Continuity in CSR Thinking

After Harvard University Professor Michael Porter introduced the concept of “creating shared value” in 2011, CSV emerged as a buzzword in business circles, partially eclipsing CSR. And after the sustainable development goals were adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015, it quickly became fashionable to replace “CSR” with “SDGs” or just “sustainability.” More recently, the GPIF’s new investment policy has put the spotlight on ESG. The result has been a bewildering proliferation of three-letter acronyms, made all the more confusing by the fact that their definitions and usage vary by region and even by individual writer.

Amidst all of this superficial flux and complexity, however, the underlying concept of social responsibility has remained largely unchanged. It appears rather that these new terms were introduced to highlight and clarify aspects of CSR in specific contexts.

The concept of CSR as it developed in Europe focused on both the positive and negative impacts of business activity. By contrast, CSV highlights the creation of value. More specifically, Michael Porter defines CSV as a means of generating business profits while creating social value. Accordingly, philanthropy and other forms of CSR that do not profit the business cannot be called CSV. The SDGs are in essence an agenda for addressing global challenges using the CSV approach. And ESG investing is a means of channeling investment funds into businesses that adopt this sustainable approach. All these concepts are interconnected, and each has undoubtedly helped the principles and practices of CSR take hold in various sectors of business and society.

The SDGs have played a particularly important role in establishing a common international language of sustainability. In addition, they have caught the attention of industry, in part because they address common global issues (not just problems facing the developing world), and in part because they highlight market and investment opportunities from infrastructure development and technological innovation. In 2016, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development called attention to the need for an additional $2.5 trillion in annual investment in order to reach the estimated $4 trillion needed to achieve the sustainable development goals by 2030.[2] A 2017 report by the Business and Sustainable Development Commission indicates that opportunities related to the SDGs could yield $12 trillion or more in additional global growth and create 380 million jobs by 2030.[3] Japanese companies have been actively linking their business plans to the SDGs in hopes of capitalizing on these market opportunities.

Recent Progress in Japan

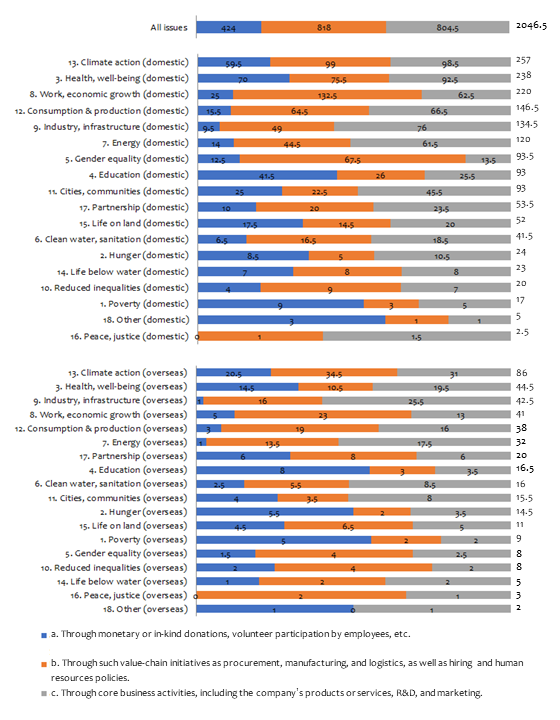

According to the results of the Foundation’s latest CSR survey (conducted from December 2017 to February 2018), the sustainability issues targeted most frequently by Japanese businesses are (1) climate action, (2) good health and well-being, (3) decent work and economic growth, (4) responsible consumption and production, (5) industry, innovation, and infrastructure, (6) affordable and clean energy, and (7) gender equality, in that order (Figure 1). Companies are inclined to deal with climate change (including natural disasters), health and well-being, industry and infrastructure, and production and consumption through their core business activities, while issues relating to work and economic growth or gender are more frequently addressed via value-chain policies or initiatives. Problems like poverty and hunger, which are more difficult to tackle directly through commercial activity, are most often targets of charitable donations and volunteer work.

Two emerging focal points in terms of SDG-oriented business development are international export of infrastructure—a traditional strength of Japanese industry—and use of innovative technology and solutions to address issues facing Japan’s rapidly aging society (and ultimately many other societies as well), including a shrinking labor force and mounting healthcare challenges. Unfortunately, Japan is in danger of being left behind when it comes to development of sustainable technology and infrastructure. Europe and China are both far ahead of us in the promotion of renewable energy and electric vehicles. Japan also lags behind in the development and adoption of new business models, such as the sharing economy, and in the digitization of commercial transactions. Despite Japan’s reputation as an exporter of technology, Japanese industry has thus far offered little in the way of new solutions to key social problems. Products and technologies cannot solve these issues by themselves. The real value lies in solutions designed from those products and technologies.

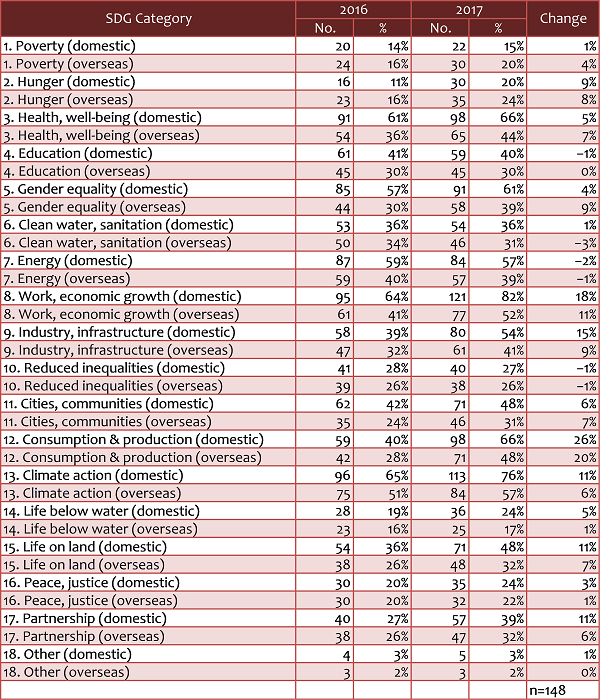

In the latest CSR survey, 66% of responding companies identified consumption and production as a high-priority domestic issue, an increase of from the preceding year (Figure 2). This increase can be attributed in part to the upcoming Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2020, as the organizing committee has been spurring debate of food-loss issues while deliberating strategies for food and beverage services at the 2020 Games. Efforts to address the problem of microplastics have also gathered momentum with the launch of initiatives for recovery and recycling of plastic waste polluting the marine environment. The European Commission took aim at these problems with its 2015 Circular Economy Action Plan, which seeks to promote the transition toward a “closed loop” economy while fostering sustainable growth under a new economic model.[4] It seems such issues are attracting growing interest in Japan as well.

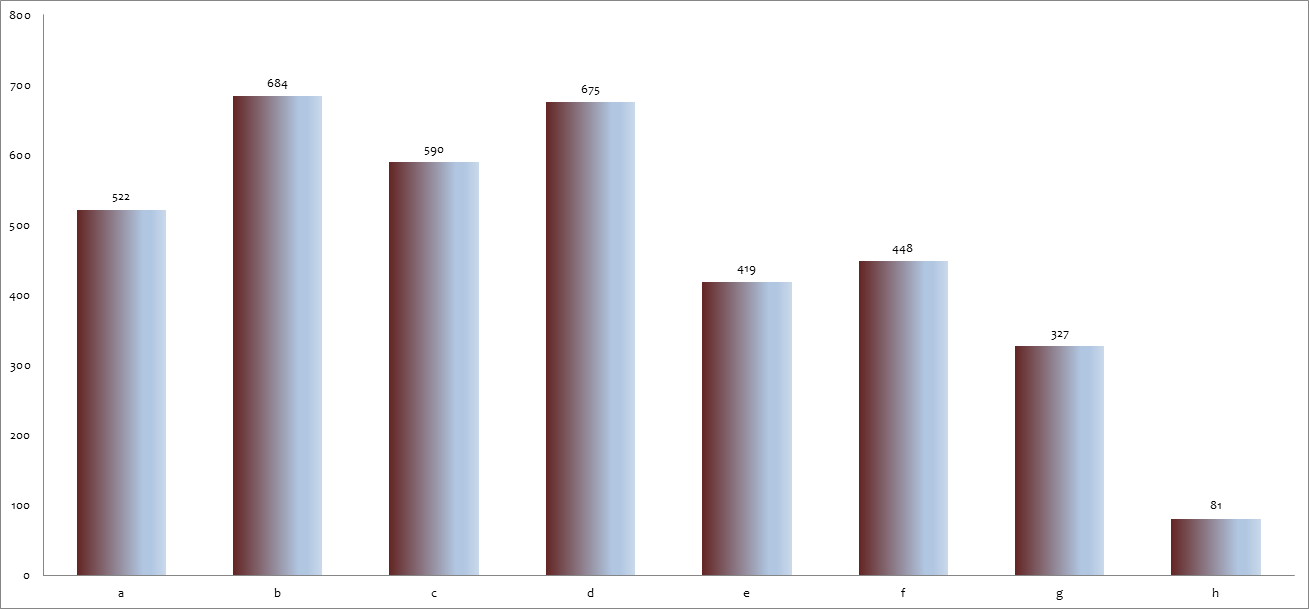

The focus of CSR activity in Japan has gradually shifted from corporate philanthropy to value creation. In the latest CSR survey, many respondents acknowledged the efficacy of CSR in improving brand image. Some also indicated that CSR had contributed to the development of new business opportunities or boosted corporate profits (Figure 3). These are clear signs that CSR is taking hold within the mainstream of business management.

But the true integration of CSR into business management requires the application of economic principles to CSR planning and assessment. From that standpoint, there is a need for objective indicators to assess the efficacy of such activity, including the total value of investment—a key challenge for CSR going forward. Disclosure of such performance indicators could ultimately emerge as a key buying factor. If Japanese companies wish to capitalize on their professed commitment to the SDGs, they need to provide clear data on the efficacy of their contribution and adopt indices of competitiveness encompassing factors other than cost and quality.

Figure 1. How Companies Address Sustainability Issues

(Number of responding companies, n=279)

Figure 2. Priority Issues for Japanese Businesses

(Number and percent of responding companies, n=148)

Figure 3. Perceived Benefits of CSR Activities

(Number of responding companies, n=274)

- Created new business opportunities

- Facilitated recruitment, human resources development

- Raised quality of products, services, technologies

- Improved product image

- Gained recognition as socially responsible company

- Bolstered earnings

- Helped in identifying, analyzing, or mitigating risk

- No perceived impact

CSR on the Cutting Edge

The world’s leading CSR companies have already integrated social responsibility into their business strategies. The key characteristics of such companies are (1) clarity and consistency of corporate purpose and value creation, (2) compatibility between the company’s management agenda and CSR programs, and (3) correlation between CSR activity and economic value. In the following, I would like to briefly introduce two Dutch companies regarded as exemplary in their commitment to CSR.

The first is chemical giant AkzoNobel, which manufactures paints and coatings under the corporate motto “Tomorrow’s Answers Today.” AkzoNobel has fully integrated its sustainable growth strategy into its business strategy and applies an EES (economic, environmental, and social) management framework to a wide range of activities. It is noted especially for measures that have cut manufacturing costs while reducing the environmental burden across the value chain. AkzoNobel is also committed to community involvement and employee skills development with a view to laying the foundation for sustainability-oriented innovation. Finally, it measures the outcomes and impacts of these activities and reports the results publicly.

Another pioneer of CSR is the life insurance company Aegon, also based in the Netherlands. In its corporate profile, Aegon stresses its commitment “to acting responsibly and to creating positive impact for our stakeholders” in pursuit of its purpose, “to help people achieve a lifetime of financial security.” Identifying its main stakeholder groups as customers, employees, investors, business partners, and the wider community, Aegon clearly defines the value it seeks to create for each group. And like AkzoNobel, it assesses its own performance vis-à-vis various indicators of value creation and reports the results. Aegon’s business strategy is characterized by its consistent focus on shared value and material issues.

One executive at a progressive firm told me, “Top managers have to understand their value chain. An executive who doesn’t know where things are made and by whom, or who is using the company’s products and how, doesn’t deserve to be called a top manager.” However, the truth is that not many Japanese corporations conduct CSR management across the value chain. And only a precious few do so to the extent of measuring outcomes and impacts. It may seem a daunting task, but simply tackling the challenge is a worthwhile exercise, since it can provide a unique opportunity to see the extent of a company’s impact.

The European Commission defines CSR as “the responsibility of enterprises for their impact on society.” As such, it can be an important tool for reevaluating management’s perspective on the broader boundary of their responsibility.

CSR and the Changing Rules of Global Business

In recent years, regulatory agencies around the world have adopted a raft of new rules oriented to the protection of human rights and the environment.

With respect to human rights, many governments have instituted new disclosure requirements since the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011. In 2012, the state of California enacted the Transparency in Supply Chains Act. Britain incorporated supply-chain-transparency requirements in its Modern Slavery Act 2015. In February 2017, the French government passed the Duty of Vigilance Law imposing strict due-diligence and reporting requirements, and the following August the Australian government introduced its own Modern Slavery Act (enacted in late 2018). In the Netherlands, deliberation continues on the Dutch Child Labor Due Diligence Law.

Similarly, action on the environment has accelerated since the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference (COP 21) in Paris. During this time—as Japan grappled with domestic energy problems in the wake of the 2011 nuclear accident—investors have been eclipsing business and nonprofit leaders as the most prominent international players. One reason is that climate change has come to be regarded as a financial issue, as indicated by the establishment of the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). It is as if policies on climate change had been placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance or the Financial Services Agency instead of the Ministry of the Environment. In recent years, major institutional investors, including CalPERS (California Public Employees’ Retirement System), CalSTRS (California State Teachers’ Retirement System), BNP Paribas, and life insurance giant AXA have flexed their muscles by divesting from thermal coal power, a major contributor to climate change.

Such investment decisions are grounded in economic reality as well as environmental concerns. The Carbon Tracker Initiative, an independent financial think tank that analyzes the impact of the energy transition on capital markets, warns that many of today’s fossil-fuel reserves and projects will become “stranded assets” if countries keep their commitment to reduce carbon emissions in keeping with the Paris Agreement.[5] Britain and Germany have announced plans to end sales of new gasoline and diesel cars within the next few decades (Britain by 2040, Germany by 2030), and China is said to be deliberating a phase-out as well. Faced with the likelihood of such game-changing policies, companies are under pressure to rethink their allocation of resources.

In its final recommendations, released in June 2017, the TCFD calls on corporations to disclose the potential financial impact of climate change on corporate assets and profits—including such transition risks as tighter environmental regulations and changes in the competitive environment as a result of new technology, as well as such physical risks as natural disasters and rising sea levels—along with management’s strategy for managing those risks.[6]

Disclosure rules may not seem like stringent requirements in and of themselves, but they are an effective means of leveraging competition to foster socially responsible behavior. Companies whose conduct falls short are likely to face social criticism and be shunned in the marketplace. Furthermore, the example of progressive companies is likely to raise society’s expectations of corporate conduct overall. In this way, disclosure helps shift oversight functions from government to civil society and encourages companies to raise the bar voluntarily. It exposes businesses to CSR competition, whether they like it or not; encourages them to benchmark their own performance against their competitors and society’s rising expectations; and keeps them accountable to stakeholders.

Disclosure also provides data that stakeholders can use to make informed decisions. Brand-driven companies and government agencies can use such information to incorporate human-rights factors in their procurement decisions, much as shoppers consult food labels for information on ingredients and country of origin. At a time when products are becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish in terms of cost and quality, CSR is emerging as a significant buying factor.

Just as importantly, investors have begun to apply such nonfinancial criteria when making investment decisions. In the European Union, where people have access to information on how their pension contributions are being used, ordinary citizens take a more active interest in institutional investment decisions. Pension managers and investment analysts have a fiduciary duty to the plan’s beneficiaries, and the beneficiaries want a sustainable society.

Unfortunately, in Japan, public interest in institutional investing is still low, and many institutional investors and analysts remain skeptical about returns on ESG investing.

Meanwhile, corporations have begun to complain about the methodology used by ESG ratings agencies. As CSR gives rise to new criteria for competition, there is a growing need for ESG literacy among investors and other stakeholders.

Conclusion

The idea of contributing to society through one’s core operations is by no means foreign to Japanese business. Our older, more established corporations have stressed service to society since their inception. Perhaps the GPIF’s new emphasis on ESG investing is the impetus needed to spur a renewal of this commitment. In Japan, shareholders have traditionally had little voice in management, but that is changing. The fiduciary responsibility of the GPIF and other pension funds is to its beneficiaries—the current and future citizens of Japan. Keeping their interests in mind, the new shareholder-centered management must ultimately be oriented to sustainable growth and the long-term health of our society.

The world is building a new order that integrates sustainability into economic activity, with disclosure at its core. The goal is to change the flow of capital by quantifying and clearly communicating social value and costs. Japan has made an important move in this direction, but to play an active and meaningful role in the creation of the new order, it must substantially boost its communication efforts beyond its borders and engage with a broader range of stakeholders. As things stand, the world knows too little about Japan, and Japan understands too little about the world. Assembling ideas and innovations from around the world, Japan should take the initiative in developing and propagating a new model of sustainable capitalism.

Keiichi Ushijima

Japan CCaSS Leader, Principal, Climate Change and Sustainability Services (CCaSS), Ernst & Young. Worked in corporate planning for a major life insurance company before joining Hitachi, where he helped spearhead business and organizational reform and develop the Hitachi Group’s CSR and sustainability strategy. Joined EY Japan in 2013 and assumed his current position in 2014. Also serves on the Global Environment Committee of the Ministry of the Environment’s Central Environment Council and is an adjunct lecturer at the Graduate School of Economics and Management, Tohoku University.

[1] https://integratedreporting.org/resource/international-ir-framework/.

[2] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/07/blended-finance-sustainable-development-goals/.

[3] http://report.businesscommission.org/uploads/BetterBiz-BetterWorld_170215_012417.pdf.

[4] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/circular-economy/index_en.htm.

[5] https://www.carbontracker.org/reports/2-degrees-of-separation-transition-risk-for-oil-and-gas-in-a-low-carbon-world-2/.

[6] https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/final-recommendations-report/.