- Article

- Fiscal Policy & Social Security

Japanese Healthcare at a Crossroads (1): Toward Integrated Community Care

October 30, 2017

Japa n is facing tough choices as demographic aging threatens the sustainability of its vaunted universal health insurance system. Health policy expert Kiyoyuki Tomita sheds light on the future of healthcare in Japan.

* * *

Dramatic changes in the demographic structure of Japanese society are fueling rapid increases in the cost of healthcare, including nursing care for the elderly. Concerns about the sustainability of Japan’s system of universal health insurance continue to mount despite a raft of cost-oriented reforms at the national level. Insecurity, ironically, has become the defining feature of our social security system. To address these concerns, fundamental healthcare reforms are being discussed focusing on two interconnected themes: qualitative improvement and community-based care.

Limits of Quantitative Reform

For more than a half-century, Japan’s healthcare policies have focused on the quantitative issues of access and cost. Initially, the government was under intense pressure to ensure that as many citizens as possible had access to healthcare, and it responded to this quantitative challenge by instituting a nationwide system of universal health insurance and making healthcare services free to the elderly. Later, with the goal of universal access largely realized, soaring healthcare expenditures began to place an unsustainable burden on government finances, and policymakers were faced with the necessity of finding ways to rein in healthcare costs

Since the 1980s, the central government has adopted a series of cost-control measures, including a fee-schedule revision process that factors in projected government expenditures and the institution of a new insurance scheme for the elderly with cost sharing. Under the 1985 amendment of the Medical Service Law, the central government also attempted to control hospital expansion in the regions, but with facilities rushing to invest under the deadline, capacity continued to expand until around 1990, further complicating efforts at quantitative control.

Meanwhile, outlays under the Long-term Care Insurance system, launched in 2000, continue to soar as Japan’s elderly population grows, forcing the government to consider an overhaul of the system’s financing and benefit structure.

From Quantity to Quality

As we have seen, a quantitative approach has dominated healthcare reform in Japan until now. Recently, however, efforts to reform the system from the standpoint of quality have begun to gain traction. Among these is the Integrated Community Care System for the elderly, which the government hopes to have in place by 2025. This initiative envisions a network of community services that will help the elderly live as they choose, in their own communities, for as long as possible, with an emphasis on supporting independence and dignity. This is not merely a matter of controlling costs. It is also closely tied to quality of care and quality of life.

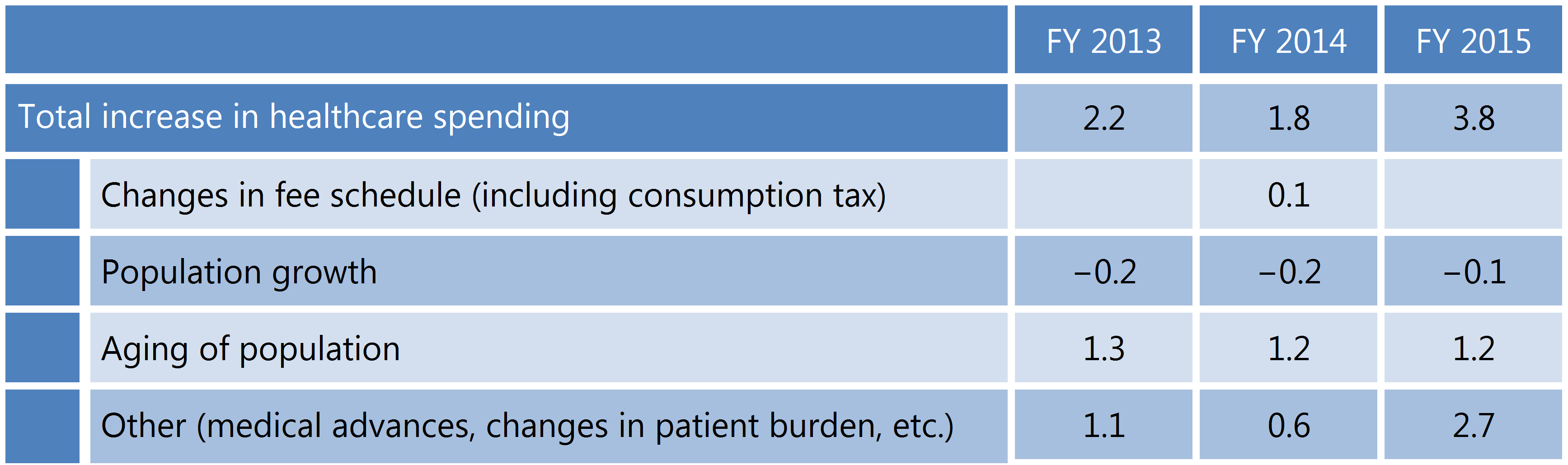

Impact of Key Factors on Healthcare Spending (% growth)

Of course, Japan has made great strides in the quality of healthcare, thanks primarily to the unfla gging efforts of medical researchers and healthcare providers. Rapid progress in medical science and the adaptation of such advances to clinical practice, along with the development of nursing services geared to the diverse needs of the elderly, have conferred countless benefits on patients. But our healthcare policies have done relatively little to incorporate such qualitative advances into the system.

For example, the basic fee-for-service system of reimbursement is strongly oriented to quantitative management and takes very little account of such qualitative factors as regional and technological discrepancies and efficacy of treatment. Since 2003, some progress has been made in encouraging a systemic focus on quality with the DPC (diagnosis procedure combination) system of bundled payment, combined with the standardization of inpatient treatment through the use of critical paths. Still, this approach is limited to certain hospital services and has not provided an answer to the larger question of how to measure and improve the overall quality of healthcare.

However, an awareness of the need for a new integrated, qualitative approach is apparent in the Community Health Care program, already underway. Under this initiative of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, each prefecture is required to compile forecasts for local demand for various types of medical care in 2025 and use those forecasts to draw up a comprehensive plan based on differentiation and coordination of healthcare functions among different types of providers. While the means is quantitative, the purpose is the qualitative enhancement of overall care through better coordination among different providers in various healthcare settingsーin-home care, outpatient care, different levels of inpatient care, and so forth. Planning a comprehensive regional healthcare plan will mean developing qualitative health and quality-of-life targets appropriate to each region and designing an integrated system to achieve those [1] targets.

And this brings us to the need to shift responsibility for healthcare policy from the central government to the local community.

From Central to Local Control

In Japan today, health- and nursing care is a major component of national policy. Healthcare-related expenditures currently account for about 15% of the general account budget. The national government spends more than ¥40 trillion on health insurance benefits and another ¥10 trillion on long-term care. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Japan spends 10.9% of its gross domestic product on healthcare, placing it in the top tier internationally.

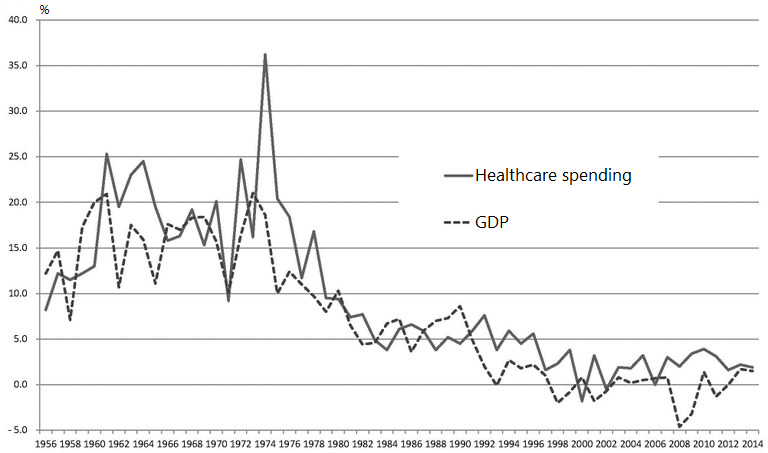

Annual Growth in Healthcare Spending and GDP

Costs have continued to rise as the central government initially sought to expand, and subsequently to limit, the availability of services. The abovementioned nationwide fee schedule interferes in the relationship between providers and patients by specifying the amount providers can charge for each treatment, procedure, drug, and nursing-care service. The fee schedule for medical care is revised every two years; that for long-term care, every three years. While such frequent revisions may make the system more responsive to changes in the environment, they also give policymakers greater room for discretionary adjustments.

At the same time, local governments are key players in the nation’s healthcare system. Each prefecture draws up and submits administrative plans for medical facilities, cost control, and promotion of public health, while municipalities oversee long-term care and other community welfare services. The aim of both the Community Health Care initiative (for general medical care) and the Integrated Community Care System (for the elderly) is to strengthen the autonomy of local governments in healthcare policy planning.

Healthcare must respond to a wide range of social changes, including the impact of rapid demographic agingーwhich has pushed chronic and lifestyle diseases to the foreーand advances in information technology and the transportation network. But these changes and their impact vary significantly from one locale to another. Regional differences in population and demographic structure in particular are growing ever more pronounced. It follows that each region should formulate its own blueprint for improvement, based on its particular circumstances and trends, and that local governments and community members should take the lead in healthcare policy planning and decision-making.

Under the Community Health Care initiative (for general medical care), each prefecture is required to set up a Community Health Care Council in which prefectural authorities and representatives of the healthcare community can deliberate policies and practices for optimum allocation and coordination of different modes of medical care. Under the Integrated Community Care System (for the elderly), each municipality will establish a community care support center to gather feedback on local issues relating to the integrated care system.

The basic goal is to gradually shift responsibility for healthcare policy to the local level. However, it is not sufficient simply to transfer responsibility from the central government to the prefectures. We also need to ensure that the prefectures and municipalities have the power, capacity, and mechanisms to meet those responsibilities. This is what decentralization is about.

Putting It All Together

A critical component of a quality community-based healthcare system is coordination and communication centered on the patient and his or her family. This is the role of the primary care provider. The success of the reforms discussed above will hinge on our ability to enhance primary care so as to strengthen coordination and cooperation between various local medical, eldercare, and welfare providers. The holistic, interdisciplinary perspective of the primary care provider is vital to a program like the Integrated Community Care System, which calls for community-wide cooperation and coordination. It is time to assign a clear and central role to primary care within the Japanese healthcare system from an integrated, comprehensive perspective.

Of course, Japan has its primary care providers. These are the neighborhood practitioners that many community members rely on for their basic medical needs. However, the role of primary care is neither as central nor as clearly defined in Japan as it is in other countries. In Japan, anyone willing to pay the standard copay is free to visit the hospital of his or her choice and consult with a specialist, even without a referral. Consequently, many people have no regular primary care physician. Only now are we seriously beginning to question the wisdom of such a free-access system.

The sustainability of our healthcare system demands a balanced approach to achieve the seemingly contradictory goals controlling costs while improving quality.

Translated from “Tenkanki mukaeta iryokaigo seido: Iryokaigo seisaku no ninaite wa chiiki ni,” Kosei Fukushi , September 12, 2017; augmented with additional text by the author. Courtesy of Jiji Press.