Traditional local food culture is fast dying out in Japan, and the case of tochi (Japanese horse chestnut) trees illustrates the threats to ancient customs that the country now faces. The "Rediscovering the Treasures of Foods" project explores why the tochi tree is so important to the preservation of Japan's culture, tradition, and conservation.

Sharing an Ancient Culture

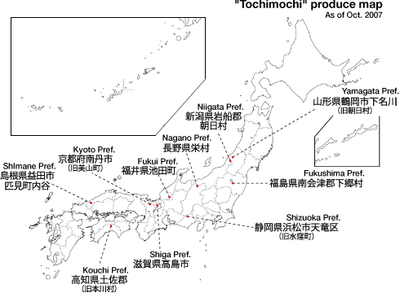

The culture of eating tochi (Japanese horse chestnut) survives only in abundantly wooded areas with clear-running streams. This culture remains dotted across Japan, from Shikoku to the northernmost tip of Hokkaido. Common forests and virgin tochi forests have been preserved in the rugged mountainous areas of Shizuoka, Tottori, Nagano, Gifu, Niigata, Yamagata, and Iwate prefectures. Of these, certain areas in Japan still have traditional confectioners that make rice cakes, rice crackers, and candy using tochi seeds and have kept up their family businesses around unique processing systems. The 1980s saw a rise in movements led by local women to preserve traditional foods by producing and directly marketing them. Today, however, only a few home-based producers continue to make local tochi foods, and passing down the culture has become difficult due to the rapid aging of the community.

Treasuring Tochimochi

Ikeda-cho in Fukui Prefecture, which I visited for this article, is 92 percent forested, surrounded by tall mountains, and blessed with delicious spring water. It is thanks to interaction with the mountain folk living nearby that the tochimochi (rice cakes with tochi seed) have been cherished here from days of old as a local specialty. Nearly 30 people in Ikeda-cho still know how to make tochimochi, most of whom make the food for their families and neighbors in an attempt to keep the culture alive.

Tochi, a large-leafed deciduous tree, can grow as tall as 30 meters. The culture of eating tochi seeds is said to have existed in Japan since the Jomon period (14000–4000 BC). Unlike the Japanese chestnut tree, the nut of which was also part of the Jomon diet and which lives for only 30 to 40 years, the tochi are valuable trees that often become giants of over 300 years old and bear large seeds even in old age.

The seeds are so bitter that they are hardly edible and are not eaten at all in the West. The roadside trees commonly known in Japan by the French name marronnier, also known as horse chestnut in English, are cousins of the tochi.

Tochi continued to be a staple food in rugged mountainous regions in Japan until after the end of World War II. The folklorist Tomio Yuki suggests that the distribution of the tochi-eating culture overlaps with the culture of matagi, group hunters who use traditional methods to hunt in the mountains during winter. Riches of the mountains, such as tochi and mushrooms, were indispensable in a diet consisting mainly of turnips and cereals and occasionally supplemented by boar, wild birds, and other meat. This type of diet is reminiscent of what Jomon people living far from the coast would have eaten.

Even today, reserves of food for times of disaster are referred to as “the tochi in the attic.” There also used to be a custom of presenting several tochi trees in lieu of a dowry when marrying off a daughter. Tochi foods continued to be produced for times of famine and other emergencies in mountain villages across Japan, particularly in regions that had no rice paddies, no matter the labor involved.

The custom of eating tochi quickly began to decline, however, between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s. One of the major reasons for the decline is that tochi trees were cut down to make room to plant fast-growing Japanese cedar trees. The other reason is a change in diet; easy-to-prepare food is now widely available, whereas tochi seeds require almost a month of preprocessing. And perhaps the most worrying reason is that people who have tochi-processing skills are aging.

To eat tochi seeds, they must be soaked in a clear stream for days and treated with wood ash in order to take out the harshness of the taste. Every region is similarly challenged with the difficulty of obtaining the ash needed for this ancient process. The sources of wood ash include the astringent Japanese oak, tochi bark, buckwheat chaff, and zelkova. Unfortunately, Japanese oak trees are dying from a plague that has been spreading across Japan over the past few years.

More importantly, tochimochi is inseparably linked to the lifestyle of living in houses with a traditional irori (open hearth). The open hearth not only kept alive the culture of sitting and chatting around the fire, but the ash was used to remove the harshness of the tochi seeds, while the shitsu (attic) above the hearth kept the seeds from either molding or freezing. As open hearths were removed and oil heaters, electric water boilers, and refrigerators came into widespread use beginning in the mid-1950s, ash quickly became hard to obtain. And because of this lack of demand for wood ash, it has actually become a costly product.

As the culture of eating tochi dies out, the only tochi food that has managed to survive is tochimochi, often prepared for the New Year and other festivities. Tochimochi is a relatively new food and something of a delicacy that has come to be eaten only since rice cultivation was realized in mountainous areas. It became popular in the Edo period, when people living in these areas went to the trouble of making terraced fields in the desire to eat rice, and the rice was then used to enhance the ancient culture of eating tochi.

Following World War II, Japan planted excessive amounts of Japanese cedar trees. Since then, however, Japan has come to import more than 80 percent of its lumber, and Japanese cedar forests have ceased to be taken care of, causing their conditions to go from bad to worse. Dam construction has also contributed to the decline of the tochi-eating culture. Tokuyama-mura in Gifu Prefecture, which had a rich tochi-eating culture, has sunk under a dam, and plans are under way for building a dam in another tochi-eating area, former Miyama-cho (now part of Fukui-shi) in Fukui Prefecture.

There is a saying in Shizuoka Prefecture that goes, “He who cuts down tochi is a fool, he who plants tochi is a fool.” The moral here is that you should not carelessly cut down a valuable source of food, as it will take about three generations for the tree to bear seed. In other words, what is once lost will take a mighty long time to replace.

It is a devastating loss for Japan to allow a tradition that its ancestors have passed down for centuries to be obliterated in just four decades.

A Labor of Love

The value of tochimochi cannot be discussed without taking into account the trouble of processing the seeds. Accompanying 67-year-old Tomiko Hasegawa and 71-year-old Tomiko Shimizu from Ikeda-cho, I learned about the difficulties of going into the mountains and collecting the seeds. Large virgin forests aside, tochi trees mostly grow by streams, and picking seeds while walking along a treacherous course upstream takes both skill and practice. But when one actually picks a seed, the glossy sheen of its skin rinsed by the crystal stream is appetizing indeed. More seeds than we could carry had fallen from just two trees, and I felt I could understand why the ancients craved to eat these seeds in spite of the immense trouble it takes to gather and prepare them.

Fumiko Hasegawa says, “When we were young, my husband and I would pick five to six bales [300-360 kilograms] a year,” but today they can only manage one bale at best. “You can pick as many tochi seeds as you like, but bringing them all down the mountain is the trouble,” she laments. This process is toilsome and is therefore one of the reasons why the custom needs to be imparted to younger generations.

Moreover, tochi trees have fertile and infertile years. I was taken on a 50-minute drive from Ikeda-cho to Ono-shi near Gifu Prefecture—home to one of the virgin tochi forests still remaining in Japan. But the trees in this area were infertile this year, and not a single tochi seed had fallen. This fluctuation appears to be one reason why the art of preservation is so essential.

Finally, extracting the bitterness from the tochi seeds takes about a month. The procedure includes soaking the seeds in running water for about a week, drying them for preservation, and soaking them again for a week before use. Then the seeds need to be immersed in boiling water, peeled with a special peeler, soaked in water again for several days, and added to a mixture of warm water and ash. A day later, the seeds are ready to be frozen for storage or steamed and pounded with glutinous rice to make tochimochi.

The processing of tochi seeds varies by region, and Hasegawa learned her method many years ago at a mountain village in Tottori Prefecture. She uses a simple wooden peeler called tochinuki that has served her for three decades and was popularized in the Taisho era (1912-1926). People mostly peeled tochi seeds with their mouths before the advent of this tool, so they would snack on pickles and herring to take away the aftertaste. Tochi peeling was no occasion for pleasant conversation.

Today, given their scarcity, the ratio of tochi seeds used in tochimochi is about half that of rice in most regions. But it is said that the more tochi, the more flavor, and the people of Ikeda-cho cook tochimochi with equal parts tochi seed and rice.

Rediscovering the Treasures of Food Project

Every one of Japan’s regions was once blessed with an abundance of its own traditional foods, including both ingredients and processed items. The rapid acceleration of globalization and the development of food distribution systems, however, are resulting in a leveling and standardization of this diverse food landscape. As a result, small producers are having trouble finding people and funds to carry on their businesses, and Japan faces the possibility that many of its foods will no longer be produced.

The “Rediscovering the Treasures of Food” project is a search for the hidden riches among food products that are in danger of discontinuation despite their value. Creating a variety of media content about these foods will allow information to be shared broadly, ideally leading to an increase in support for their producers.

Natsu Shimamura is the leader of the “Rediscovering the Treasures of Food” project and is also an author of many books, including Suro fudo na jinsei! (Slow Food Life!), Itaria no maryoku (The Magical Power of Italy), and Suro fudo na Nihon! (Slow Food Japan!).