How to Measure Scope 3 Emissions: Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Primary Data Use

March 15, 2023

C-2022-001-3WE

In an article translated from the Foundation’s CSR White Paper 2022, climate and sustainability expert Kae Takase explains how scope 3 emissions may be measured using primary data in ways that balance accuracy and efficiency.

* * *

Momentum for Net-Zero Commitments throughout the Value Chain

The global movement for decarbonization is rapidly gaining momentum. Countries and territories with targets for achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions already account for more than 70% of global emissions (Climate Watch 2022). When businesses are figured in, more than 90% of the global economy is covered by a net-zero target of some sort, according to one analysis (University of Oxford 2021).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change defines net-zero GHG emissions as a “condition in which metric-weighted anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are balanced by metric-weighted anthropogenic GHG removals over a specified period” (IPCC 2021). The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) sets more stringent criteria: reduction of all value-chain emissions by at least 90% (in most sectors) by 2050, in line with 1.5°C pathways, combined with permanent removal of any residual emissions inside or outside the value chain (SBTi 2021b).

Two key points to keep in mind in this context are that (1) each company is responsible for its entire value chain, and (2) companies cannot offset their value-chain emissions with carbon or GHG reduction credits from outside their value chain.

The SBTi was established in 2015 to help align companies’ emissions reduction targets with the goals of the Paris Agreement. In keeping with GHG accounting protocols, it divides emissions into three categories. Scope 1 consists of a company’s direct emissions, scope 2 of indirect emissions from the generation of secondary energy, such as power, heat, steam, and cooling, purchased by the reporting company, and scope 3 of all other indirect emissions across the company’s value chain, including suppliers and end-users.

With respect to scope 3, the SBTi originally required simply that each company with scope 3 emissions amounting to more than 40% of its total emissions set reduction targets—at any level—covering at least 67% of its scope 3 emissions. But version 5.0 of the SBTi criteria, which came into effect in July 2022, adds more rigorous quantitative requirements. For example, when absolute targets are adopted, the average annual rate of reduction must be more than 2.5% (25% over 10 years)—the rate considered necessary to keep the rise in average global temperatures well below 2°C (that is, approximately 1.75°C ) compared with pre-industrial temperatures (SBTi 2021c). Since 2021, the SBTi has been calling for both near- and long-term science-based targets, with the latter being equivalent to net-zero emissions. In setting long-term SBTs, all companies with more than 500 employees are required to have targets that are aligned to the achievement of net zero by 2050 covering at least 90% of their scope 3 emissions, regardless of the total amount of such emissions.

Race to Zero (launched by the secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change), an umbrella campaign covering a wide range of net-zero initiatives, also toughened its minimum criteria for participation in 2022 (Race to Zero Campaign 2022), clarifying that corporate net-zero targets should cover scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

One of the programs that participated in the Race to Zero campaign was Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), which coordinates and supports financial institutions’ net-zero commitments. GFANZ currently encompasses some 450 financial institutions worldwide (including three Japanese megabanks) responsible for assets of over $130 trillion. In accordance with the Race to Zero criteria, all members of GFANZ have committed to achieving net zero in category 15 of scope 3: indirect emissions attributable to investment or financing, including facilitated emissions. The 2021 Race to Zero Interpretation Guide makes clear that this includes the scope 3 emissions of companies financed or facilitated by the reporting institution (Race to Zero Expert Peer Review Group 2021a).

We might note here that Japan’s plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 depend on using offsetting credits from overseas emissions reduction projects, and some goods currently treated as carbon neutral only achieve neutrality as a result of such offsets. Under the established common rules, companies that purchase such goods will not be able to count them as carbon neutral in their GHG inventories, since the rules require that emissions for such products be calculated on the basis of their original gas emissions intensity. Although the SBTi encourages economic contributions to compensate for the unavoidable emissions that occur in the transition to net zero, it does not permit companies to apply emission reduction credits toward their net-zero targets.

The financial institutions participating in GFANZ have committed to net-zero emissions from their borrowers and invested companies, including their scope 3 emissions, and those borrowers and companies must reach net zero without relying on offsets in the form of emission reduction credits acquired from outside their value chains. In short, companies are being asked to achieve a genuine supply-chain balance between anthropogenic GHG emissions and removals, with no more than 10% dependence (less or more for some sectors) on carbon removals.[1]

Understanding Scope 3

Scope 3 emissions are all emissions from a company’s value chain other than scope 1 and 2 emissions. In 2011, after roughly three years of development and consultation, the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a joint undertaking by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, released the Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard (Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2011a), hereafter referred to as the Scope 3 Standard.

Scope 3 encompasses 15 reporting categories, summarized in Figure 1 (drawn from the Scope 3 Standard but including updated information for category 15). The categories are divided into upstream emissions (1–8) and downstream emissions (9–15).

For each category, the standard specifies both the “minimum boundary,” or minimum reporting requirements, and optional reporting elements. For example, under category 11, emissions from “use of sold products,” the mandatory and optional reporting elements vary by the type of product. If the product sold is an appliance like a refrigerator, then the company that sold it must include emissions from the generation of electricity used to power the product over its lifetime. On the other hand, in the case of shampoo, it is optional to report emissions associated with the heating of water used in shampooing.

With respect to categories 1–4 (purchased goods and services, capital goods, fuel- and energy-related activities, and upstream transportation and distribution), it is mandatory to report “cradle to gate” emissions, that is, all emissions that occur over the life cycle of purchased products up to the point of receipt by the reporting company. For example, a company that purchases ammonia to generate electricity or buys electricity produced from burning ammonia can largely avoid scope 1 and 2 emissions, since the only by-products of ammonia combustion are water and nitrogen. But if the ammonia is made from fossil fuel, scope 3 emissions will be considerable. Since a company has responsibility for its entire value chain, the use of ammonia produced with fossil fuel will not result in lower emissions.

Here we should note that, in terms of intent, scope 3 differs fundamentally from scope 1 and 2. Under the GHG Protocol’s Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2004), double accounting of emissions within either scope 1 or scope 2 is avoided in principle. When it comes to a scope 3, however, it is often inevitable. For example, there is bound to be overlap in category 1 emissions (from purchased goods and services) reported by the purchaser and those reported by the supplier. Such double accounting is assumed in scope 3 standards.

Figure 1. Description and Boundaries of Scope 3 Categories (with notes on optional reporting)

|

Category |

Category Description |

Minimum Boundary |

|

Upstream Emissions |

||

|

1. Purchased goods and services |

• Extraction, production, and transportation of goods and services purchased or acquired by the reporting company in the reporting year, not otherwise included in Categories 2–8 |

• All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of purchased goods and services |

|

2. Capital goods |

• Extraction, production, and transportation of capital goods purchased or acquired by the reporting company in the reporting year |

• All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of purchased capital goods |

|

3. Fuel- and energy-related activities (not included in scope 1 or scope 2) |

• Extraction, production, and transportation of fuels and energy purchased or acquired by the reporting company in the reporting year, not already accounted for in scope 1 or scope 2, including: a. Upstream emissions of purchased fuels (extraction, production, and transportation of fuels consumed by the reporting company) b. Upstream emissions of purchased electricity (extraction, production, and transportation of fuels consumed in the generation of electricity, steam, heating, and cooling consumed by the reporting company) c. Transmission and distribution (T&D) losses (generation of electricity, steam, heating and cooling that is consumed (i.e., lost) in a T&D system)—reported by end user d. Generation of purchased electricity that is sold to end users (generation of electricity, steam, heating, and cooling that is purchased by the reporting company and sold to end users)—reported by utility company or energy retailer only |

a. For upstream emissions of purchased fuels: All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of purchased fuels (from raw material extraction up to the point of, but excluding combustion) b. For upstream emissions of purchased electricity: All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of purchased fuels (from raw material extraction up to the point of, but excluding, combustion by a power generator) c. For T&D losses: All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of energy consumed in a T&D system, including emissions from combustion d. For generation of purchased electricity that is sold to end users: Emissions from the generation of purchased energy |

|

4. Upstream transportation and distribution |

• Transportation and distribution of products purchased by the reporting company in the reporting year between a company’s tier 1 suppliers and its own operations (in vehicles and facilities not owned or controlled by the reporting company) • Transportation and distribution services purchased by the reporting company in the reporting year, including inbound logistics, outbound logistics (e.g., of sold products), and transportation and distribution between a company’s own facilities (in vehicles and facilities not owned or controlled by the reporting company) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of transportation and distribution providers that occur during use of vehicles and facilities (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing vehicles, facilities, or infrastructure |

|

5. Waste generated in operation |

• Disposal and treatment of waste generated in the reporting company’s operations in the reporting year (in facilities not owned or controlled by the reporting company) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of waste management suppliers that occur during disposal or treatment • Optional: Emissions from transportation of waste |

|

6. Business travel |

• Transportation of employees for business-related activities during the reporting year (in vehicles not owned or operated by the reporting company) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of transportation carriers that occur during use of vehicles (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing vehicles or infrastructure |

|

7. Employee commuting |

• Transportation of employees between their homes and their worksites during the reporting year (in vehicles not owned or operated by the reporting company) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of employees and transportation providers that occur during use of vehicles (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: Emissions from employee teleworking |

|

8. Upstream leased asset |

• Operation of assets leased by the reporting company (lessee) in the reporting year and not included in scope 1 and scope 2—reported by lessee |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of lessors that occur during the reporting company’s operation of leased assets (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing or constructing leased assets |

|

Downstream Emissions |

||

|

9. Downstream transportation and distribution |

• Transportation and distribution of products sold by the reporting company in the reporting year between the reporting company’s operations and the end consumer (if not paid for by the reporting company), including retail and storage (in vehicles and facilities not owned or controlled by the reporting company) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of transportation providers, distributors, and retailers that occur during use of vehicles and facilities (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing vehicles, facilities, or infrastructure |

|

10. Processing of sold products |

• Processing of intermediate products sold in the reporting year by downstream companies (e.g., manufacturers) |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of downstream companies that occur during processing (e.g., from energy use) |

|

11. Use of sold products |

• End use of goods and services sold by the reporting company in the reporting year |

• The direct use-phase emissions of sold products over their expected lifetime (i.e., the scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of end users that occur from the use of: products that directly consume energy (fuels or electricity) during use; fuels and feedstocks; and GHGs and products that contain or form GHGs that are emitted during use) • Optional: The indirect use-phase emissions of sold products over their expected lifetime (i.e., emissions from the use of products that indirectly consume energy (fuels or electricity) during use) |

|

12. End-of-life treatment of sold products |

• Waste disposal and treatment of products sold by the reporting company (in the reporting year) at the end of their life |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of waste management companies that occur during disposal or treatment of sold products |

|

13. Downstream leased assets |

• Operation of assets owned by the reporting company (lessor) and leased to other entities in the reporting year, not included in scope 1 and scope 2—reported by lessor |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of lessees that occur during operation of leased assets (e.g., from energy use). • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing or constructing leased assets |

|

14. Franchises |

• Operation of franchises in the reporting year, not included in scope 1 and scope 2—reported by franchisor |

• The scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of franchisees that occur during operation of franchises (e.g., from energy use) • Optional: The life cycle emissions associated with manufacturing or constructing franchises |

|

15. Investments |

• Operation of investments (including equity and debt investments and project finance) in the reporting year, not included in scope 1 or scope 2 |

• When companies apply the equity approach for consolidation, this category should include emissions by the investee not included in scope 1 or 2. For financial institutions, methodologies defined by the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) should be used (Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials 2020). |

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2011a, category 15 boundary supplemented by the author.

In addition, with regard to reporting of absolute emissions, the Scope 3 Standard clearly states that it is designed to facilitate comparisons of a company’s GHG emissions over time, not to support comparisons between companies based on their scope 3 emissions.

The Scope 3 Standard sets forth the following five principles for GHG accounting and reporting:

Relevance: Serves the decision-making needs of users, both internal and external to the company.

Completeness: Accounts for and reports on all GHG emission sources and activities within the inventory boundary.

Consistency: Uses consistent methodologies to allow for meaningful performance tracking of emissions over time.

Transparency: Discloses information on the processes, procedures, assumptions, and limitations in a clear, factual, neutral, and understandable manner.

Accuracy: Achieves sufficient accuracy to enable users to make decisions with reasonable confidence as to the integrity of the reported information (using primary data wherever possible).

Where these principles come into conflict with one another, “companies should balance trade-offs between principles depending on their individual business goals. . . . Over time, as the accuracy and completeness of scope 3 GHG data increases, the trade-off between these accounting principles will likely diminish.”

In Japan, scope 3 accounting is often poorly understood. Figure 2 summarizes and corrects some of the most common misunderstandings.

Figure 2. Common Japanese Misunderstandings Regarding Scope 3*

|

Misunderstanding |

Correct Understanding |

|

It is sufficient to calculate emissions in a few key scope 3 categories. |

Companies should begin by screening all categories and then improve the accuracy of their calculations in key categories, as by the collection of primary data. |

|

Using standard emissions intensity data from such sources as input-output tables yields stable values and accurate results. |

If fixed intensity values are used from year to year, the only way to reduce category 1 emissions, for example, would be to purchase less. The section on accuracy states that companies should place top priority on using primary data collected from suppliers each year. |

|

The accounting method used should not be changed. Therefore, accounting should begin only after one has identified the perfect method. |

Since the accounting of scope 3 emissions involves many assumptions and the use of much secondary data, it is unrealistic to aim for perfection from the outset; in fact, there is no such thing as a perfect method. Companies should strive to improve their accounting year by year, recalculating base year emissions and most recent emissions when there are changes that could significantly affect values. |

|

It is enough to use the same methods other companies use. |

The scope 3 accounting process will naturally differ according to such factors as the purpose of accounting (business goals) and the categories selected as the focus of one’s emissions reduction strategy. There is no single “correct” scope 3 accounting approach. Designing an approach means making trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency in line with one’s business goals. It is natural for different companies to adopt different approaches. |

*Excludes items mentioned in the main text.

As noted, scope 3 standards assume that there will be double counting of emissions. Under the basic process envisioned, a company first determines the overall profile and key sources of its scope 3 emissions by conducting screening, collecting primary data on emissions in high-priority areas and striving for continuous improvement reflecting the business goals of its inventory.

What Type of Primary Data Should Be Used?

Recent years have seen the rise of digital life cycle assessment (LCA) platforms that calculate a product’s life cycle data using the latest primary data provided by suppliers. This has spawned the misconception that scope 3 accounting is only possible after all pertinent LCA data has been acquired.

The Scope 3 Standard makes it clear that scope 3 accounting is a company-level process, while life cycle assessment is a product-level analysis. There are separate standards for product life cycle accounting (Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2011b). Life cycle assessment was developed for the purpose of comparing products, while scope 3 accounting is more of a macro-level process, calculating emissions across the reporting company’s value chain. Of course, under the Scope 3 Standard, it is possible for companies to make use of life cycle assessment data as primary data for their inventories, but the standard also makes clear that LCAs are not required for scope 3 accounting.

The CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), of which I was an associate director in Japan when I originally wrote this article in Japanese, operates a platform for the disclosure of environmental information geared to the needs of investors, corporations, and other users. Under the CDP Supply Chain program, launched in 2008, more than 280 major corporations (as of the 2022 disclosure cycle) have been requesting environmental data from their suppliers. Many of Japan’s biggest companies, including Toyota, Nissan, Honda, Isuzu, Kao, NEC, Fujitsu, Ajinomoto, Kobe Steel, Sumitomo Chemical, and Sekisui Chemical, annually forward the CDP’s questionnaires to their suppliers. In addition to offering a better understanding of such sustainability issues as climate change and the risks and opportunities surrounding suppliers, the program provides access to information on suppliers’ scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. This means that reporting companies can make use of primary data from suppliers (albeit from the previous year) to calculate their own upstream scope 3 emissions.

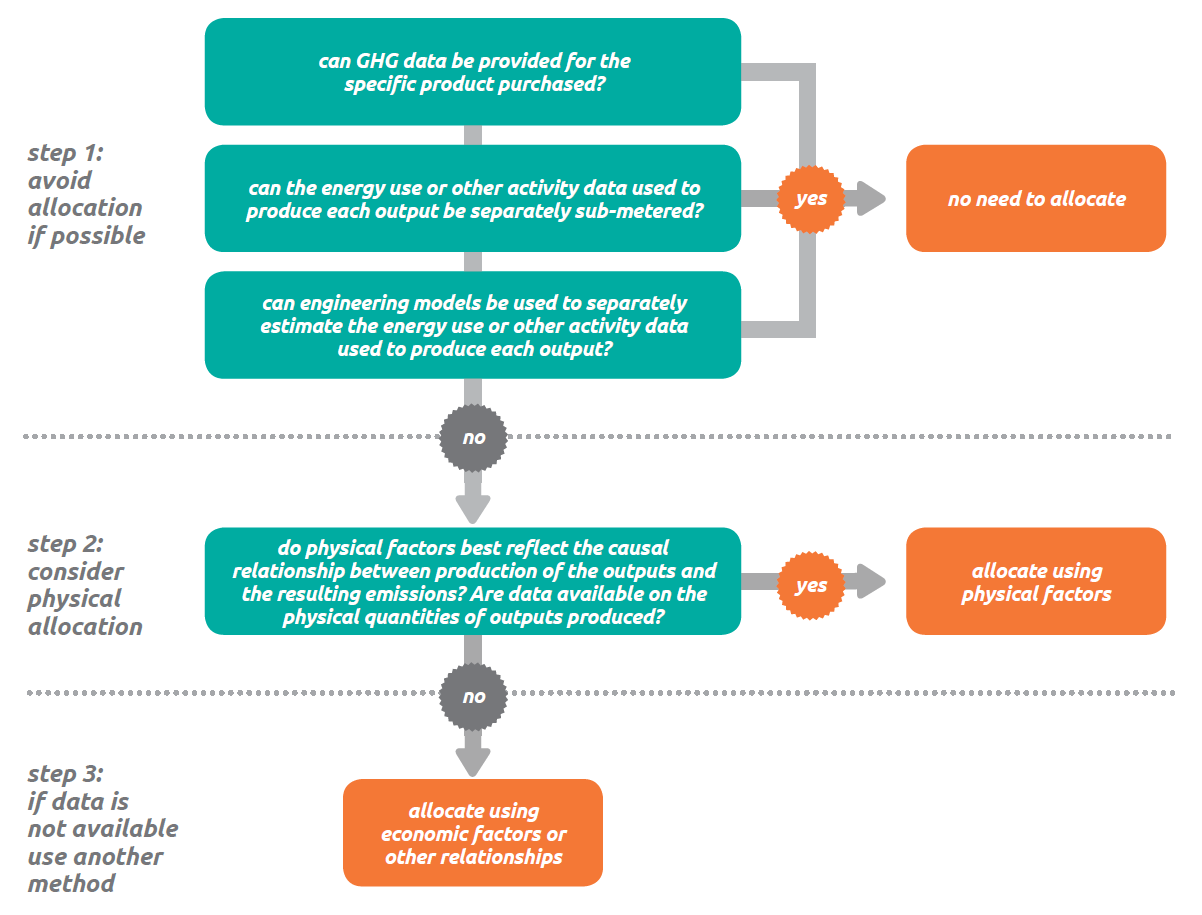

The Scope 3 Standard, issued in 2011 before the actual efforts to make use of primary data had taken hold, aims to predicate the reporting of emissions data by facility or production line. The standard states that when a facility or production line produces only one good, the contribution to the purchasing company’s scope 3 emissions can be calculated on the basis of production volume. On the other hand, if a facility or production line produces multiple goods, or if data from each production line is unavailable, it may be necessary to “allocate” emissions to different sources (using physical factors, economic factors, or other relationships). Overall, the standard advises companies to avoid or minimize allocation where possible. But where allocation is necessary, it advises them to allocate using physical factors. Only when physical allocation is impractical should they allocate on the basis of economic factors, such as the economic value of the goods procured as a share of overall sales by the supplier. The decision tree reproduced in Figure 3 explains these allocation priorities.

Figure 3. Decision Tree for Selecting an Allocation Approach*

*Accounting actually starts with step 3 and proceeds upward as inventory progresses.

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2011a.

In terms of actual accounting procedure, however, the order is generally the reverse of that shown in Figure 3. In the case of upstream emissions, for example, the reporting company first estimates emissions in its upstream scope 3 categories by multiplying the value of the goods procured from each supplier by that supplier’s emissions-to-revenue intensity. Using these rough estimates to identify key procurement items, the company then estimates emissions on the basis of physical factors or, where possible, acquires facility-level LCA data. For a company to claim that it cannot begin scope 3 accounting because it lacks facility-level LCA data is putting the cart before the horse. In most cases, it is best to begin at the bottom of this “decision tree” in order to grasp the big picture and then strive for more granularity in respect to those inputs with the greatest impact.

Scope 3 Accounting in Practice

As of 2022, there were more than 280 companies participating in the CDP Supply Chain program. In the following, I briefly describe the reality of scope 3 accounting as typically practiced by these companies.

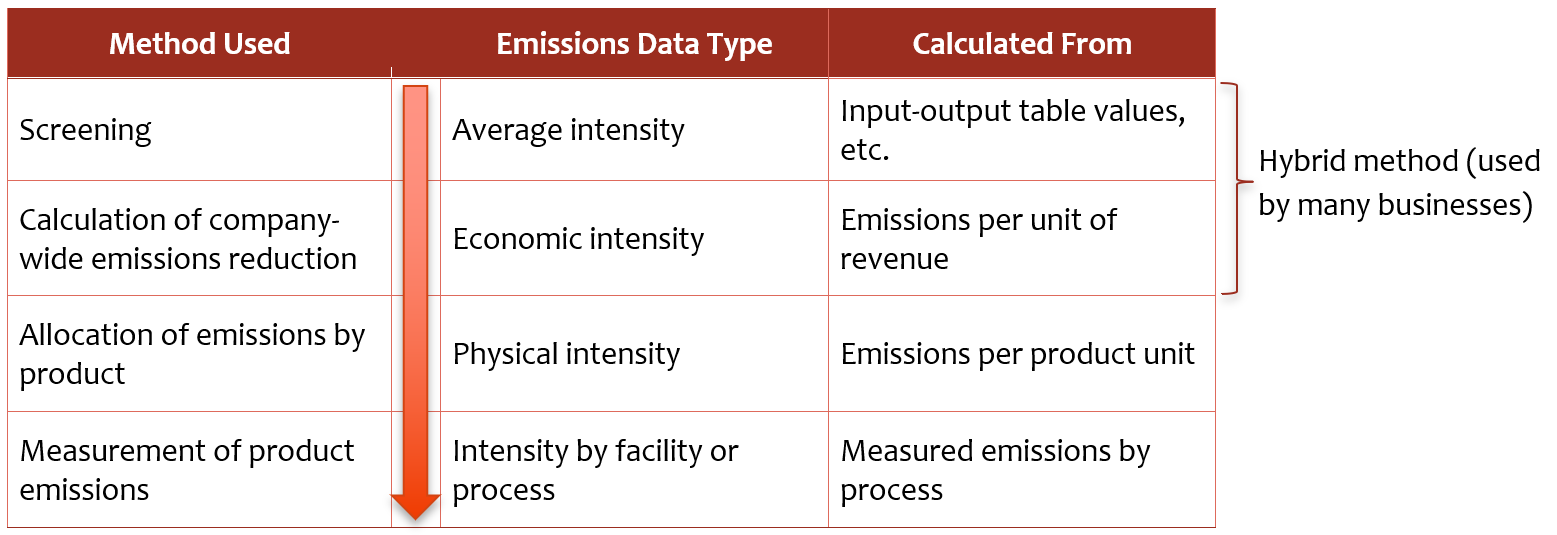

In the preceding section, I indicated that the actual procedure for scope 3 emissions accounting was the reverse of the steps shown in Figure 3. In fact, in many cases one must begin the process farther down, at a point where there is no available primary data (see upper half of Figure 4). When no primary data is available, average emissions intensity values for Japan or a specific region are used, and scope 3 accounting begins with the screening of categories using those values. On the basis of that screening, the company identifies priorities for reduction and then obtains some form of primary data for those items.

The easiest type of primary data to use at this stage is economic intensity, specifically, company-level emissions per unit of revenue. The CDP Supply Chain program offers data and tools for calculating emissions per unit of revenue as a simple method of calculating and reducing emissions. Many companies use a hybrid method that combines the use of average emissions intensity values from such sources as input-output tables (secondary data) with company-level economic intensity figures (primary data). This is the starting point for calculating the upstream scope 3 emissions that can be reduced.

As systems for real-time submission of primary data from suppliers develop and spread, the use of data on physical intensity and facility- or process-level intensity is likely to supersede the hybrid process. The time may come when there is no need to use average intensity data at all. But for now, companies need to get started on accounting and reduction in any way they can, rather than wait for the perfect scheme to be developed. The important thing is to persevere with the process, even if imperfect, while recalculating base-year and most-recent-year figures when there are changes that significantly impact values.

A good deal has changed since the Scope 3 Standard was released in 2011. Today many companies and financial institutions have committed to net zero, including scope 3 emissions. In 2011, more importance was placed on the method of allocating emissions, but today, as we strive to reach net zero by 2050, the speed of emissions reduction is a higher priority.

Moreover, with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures demanding climate action at the highest levels of corporate governance, we are seeing significant progress in disclosure and reduction measures at the company level. In a situation where speed is a top priority and companies are engaging actively with stakeholders, using company-level economic-intensity data to start is a realistic approach.

Figure 4. Practical Scope 3 Upstream Accounting Process

Source: Created by the author.

Next Steps

The GHG Protocol has begun the process of updating the Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard and related guidance (Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2022b). One reason is that the GHG Protocol’s standards are being used as reference by such regulators as the US Securities Exchange Commission and the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group in their development of accounting rules, and with the focus shifting from voluntary CDP disclosure to government-regulated reporting, there is a growing need for updates to reflect the reality of actual calculation processes and the purpose of calculation.

In September 2022, the GHG Protocol released a draft edition of new guidance relating to the land sector and removal (Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2022a). Until now, biomass has been assumed to have zero emissions on the premise that it is reabsorbed, but henceforth, actual biomass emissions and removals will be added to the reporting requirements, with calculations also expected to include not only forest management but also carbon capture and storage. The GHG Protocol plans to issue the final standard in the second quarter of 2023 after a period of consultation and pilot testing.

Scope 3 accounting standards are unique in their assumption of double counting and the leeway they provide for tailoring the accounting approach to each company’s needs and attributes. Land-use emissions and carbon removals will be included in scope 3 accounting when the new guidance is published. With these and other important elements complicating the process, we can stay on track by focusing our energies and resources on the greater goal toward which humanity is striving rather than the subtle intricacies of scope 3 allocation and accounting.

Climate change is a physical phenomenon with scientifically established causes. The purpose of GHG accounting is the attainment of humanity’s goals on the basis of science, not the enrichment of the accounting and reporting industry. Non-governmental organizations like CDP are working toward the day when they no longer have a job because the world’s climate crisis has been resolved. As part of our work, we encourage startups aiming to profit from the demand for GHG accounting to share in our goals and make their top priority the swiftest possible progress toward decarbonization, not the highest possible profits. With this in mind, they should begin the essential task of building effective frameworks for corporate scope 3 reporting and stakeholder engagement. Once that is accomplished, they can delve into the subtle intricacies of GHG accounting if they so choose.

References

Climate Watch. 2022. Net-Zero Tracker. https://www.climatewatchdata.org/net-zero-tracker. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 2004. A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 2011a. Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard. https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 2011b. Product Life Cycle Accounting and Reporting Standard. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/Product-Life-Cycle-Accounting-Reporting-Standard_041613.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 2022a. Land Sector and Removals Guidance, Draft for Pilot Testing and Review. https://ghgprotocol.org/land-sector-and-removals-guidance. Accessed October 17, 2022.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. 2022b. “Next Steps on Process to Update Existing Corporate Standards.” https://ghgprotocol.org/blog/next-steps-process-update-existing-corporate-standards. Accessed September 15, 2022.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2021. “IPCC AR6 WGIII Annex I: Glossary.” https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_Annex-I.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials. 2020. The Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard for the Financial Industry. https://carbonaccountingfinancials.com/files/downloads/PCAF-Global-GHG-Standard.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Race to Zero Campaign. 2022. Starting Line and Leadership Practices 3.0. https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Race-to-Zero-Criteria-3.0-4.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Race to Zero Expert Peer Review Group. 2021a. Interpretation Guide. Version 1.0. https://racetozero.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Race-to-Zero-EPRG-Criteria-Interpretation-Guide.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

Race to Zero Expert Peer Review Group. 2021b. “Race to Zero Lexicon.” https://racetozero.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Race-to-Zero-Lexicon.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

SBTi (Science Based Targets initiative). 2021a. Beyond Value Chain Mitigation FAQ. Version 1.0. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Beyond-Value-Chain-Mitigation-FAQ.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

SBTi (Science Based Targets initiative). 2021b. SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard. Version 1.0. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Net-Zero-Standard.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

SBTi (Science Based Targets initiative). 2021c. SBTi Criteria and Recommendation. TWG-INF-002. Version 5.0. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTi-criteria.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2022.

University of Oxford. 2021. Governing Net Zero: The Conveyor Belt. https://neteroclimate.org/governing-net-zero-the-conveyor-belt. Accessed September 15, 2022.

[1] Unlike emission reduction credits, neutralization credits can be used to offset residual emissions (generally up to 10% of the base year level) after an organization makes a claim of carbon neutrality.