- Article

- Political Institutions

Rebuilding Japanese Politics by Establishing Self-governance in Political Parties: (1) A Challenge for the New Administration

October 30, 2009

One of the motivations of those who voted for a change of government at the recent general election was a desire for the new administration to rebuild politics. The quality of Japanese politics has visibly deteriorated in recent times. The new administration is strongly aware of this and has declared its determination to break bureaucratic leadership of policymaking and unite the ruling parties and the cabinet as it runs the government.

Moreover, while issues like "hereditary politicians," politics and money, manifestoes, and electoral turnout may appear unrelated at first glance, they are all connected.

The thread that connects all of these issues is the self-governance of political parties. This is similar to how corporate governance is a prerequisite for companies wishing to improve their performance.

To rebuild politics, therefore, instead of dealing with each of the various problems separately, we must establish self-governance in political parties. This will enhance the competence and discipline of politicians and lead to the rebuilding of politics.

Before discussing specific proposals for reform, I would like to pinpoint how the various issues mentioned above are connected and where the crux of the matter lies by reviewing the workings of the parliamentary cabinet system, the political system employed in Japan. In addition, I will consider the methods of government being pursued by the new administration, including such questions as what problems they are intended to resolve and whether these methods will be sufficient.

I. The Parliamentary Cabinet System and the Current Situation in Japan

Starting Point: Party Manifestoes or Bureaucratic Mandates?

A parliamentary cabinet system is generally understood to consist of a process whereby political parties publish manifestos, the party (or coalition of parties) that wins an election and has a majority in the parliament assembles a cabinet, and ministers appointed to take charge of the policies advocated in the ruling party's manifesto implement those policies, using bureaucrats as staff. This is the true meaning of "political leadership." But in Japan, both parties and voters have tended to pay little heed to manifestoes, even though they are essential to the first step of the process, and little effort has been put into producing them. The subsequent steps in the process of "political leadership" have not been established.

The factors behind this situation include the fact that for many years the public did not need to make major political choices and the multimember constituency system that Japan employed until the 1990s. At the root, however, are problems arising from the manner in which the parliamentary cabinet system has been practiced in Japan.

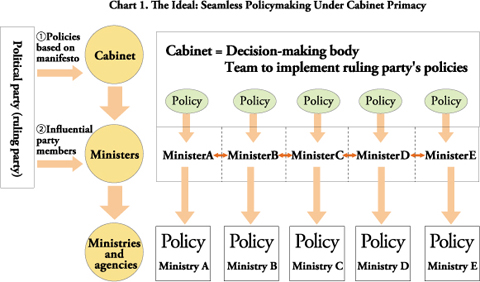

As shown in chart 1, in an ideal parliamentary cabinet system, first, the ruling party has policies based on its manifesto (1), and a cabinet comprising influential members of the ruling party is formed to implement those policies (2). Based on cabinet discussions of basic principles for managing state affairs and the order of priority of individual policies, cabinet ministers implement the policies, using the bureaucrats in their respective ministries as staff. As the cabinet considers policies from the perspective of the overall management of state affairs, this mechanism holds the interests of individual ministries in check and enables bureaucratic sectionalism and regulatory redundancy to be eliminated.

Click to view larger image

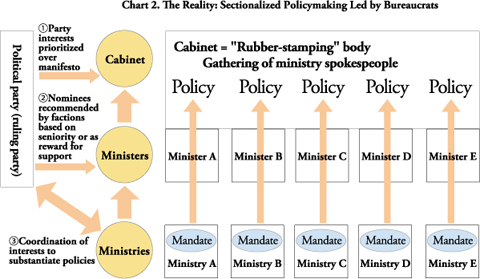

The reality of the system as it has been practiced so far in Japan, however, greatly differs from the above, as shown in chart 2. In this setup, ministries come first, and bureaucrats take charge of everything from policy formulation to implementation in areas that are within the mandates of their respective ministries. Ministers are effectively figureheads who simply "sit" on top of that structure (as shown by the fact that, at their inaugural press conferences, the vast majority of ministers read out texts prepared by bureaucrats). Most ministers, moreover, have taken to promoting the existing policies of their ministries and speaking for the ministries' interests and positions as soon as they are appointed, no matter what views they may have espoused when they were ordinary Diet members. As a result, the ministerial coordination and cabinet leadership expected in a true parliamentary cabinet system take a backseat. The priority given to past practices and bureaucratic sectionalism makes it difficult for the government to effect drastic policy shifts or to respond swiftly to changing social conditions.

Click to view larger image

Let us touch on the subject of acts of establishment, which are the fundamental laws stipulating the aims and tasks of each ministry and agency, including the abovementioned mandates.

The powers of ministries and agencies, such as approval, guidance, and oversight, are exercised based on individual laws. Despite the fact that acts of establishment do not stipulate the powers of ministries and agencies, 1 in reality each ministry and agency asserts its powers on the basis of its mandate, resulting in interagency turf wars and sectionalism. Furthermore, while in other countries government organs often adapt themselves flexibly to the policies of each administration, in Japan the acts of establishment serve to obstruct the merger, abolition, and reorganization of government bodies.

Dual Structure of Cabinet and Ruling Party

Another factor that weakens the power of the cabinet and prevents the parliamentary cabinet system from functioning properly in Japan is the dual power structure consisting of the ruling party and cabinet.

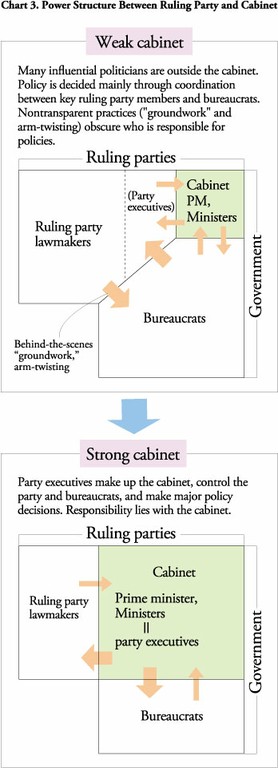

In an ideal parliamentary cabinet system, the cabinet is a team that executes the policies of the ruling party, like the "strong cabinet" in chart 3. Power within the ruling party is concentrated in the cabinet because those entering the cabinet are the party's prime movers, and ruling party lawmakers who are not in the cabinet ordinarily do not defy the cabinet's policy decisions, much less revoke them. Under the Liberal Democratic Party administrations of the past few decades, however, it became the norm for ruling party members outside the cabinet to wield more power than the cabinet, as shown by the "weak cabinet" in chart 3. As a result, many policy decisions were effectively made through repeated contact (behind-the-scenes "groundwork," negotiation, and arm-twisting) between ruling party politicians (such as the LDP's three top executives, "tribal" lawmakers with close ties to specific industries, and members of the party's policy divisions) and bureaucrats, in total disregard of the cabinet. This deviates greatly from the principles of the parliamentary cabinet system and obscures who is responsible for making government policy.

Consequently, the policies of the government have often contradicted those of the ruling party. The privatization of the postal services by the administration of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi is a typical example, as are the more recent statements by then Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries Shigeru Ishiba that he did not agree as the leader of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries with maintaining the policy of rice acreage reduction but that he was not in charge of the LDP's agricultural policies when it came to the question of how to handle this issue in the party manifesto. Under an ideal parliamentary cabinet system, ministers would never utter words like these. The simultaneous existence of the government's Tax Commission and the LDP's Research Commission on the Tax System epitomized the chronic nature of the dual power structure.

The decision-making process within the dual power structure, which has become almost institutionalized over the decades, can be summarized as follows. In the case of the LDP, the party has its own policy coordination section called the Policy Research Council, which checks the bills and other policy proposals put forward by the government (ie. the cabinet). Government bills cleared by the Policy Research Council are approved by the party's General Council before being submitted to the Diet. This is called "prior screening" by the ruling party, a practice that is virtually unheard of in other major countries. It is not unusual for government bills to be drastically modified or even rejected in this process. The rejection by politicians outside the cabinet of policy proposals that representatives of the same party drafted in order to implement the party's manifesto amounts to rejection of the parliamentary cabinet system itself. At the same time, in the sense that it entrenched the feeling that any proposal approved by the ruling party had effectively been approved by the Diet, it was also one of the factors that reduced the Diet to a mere shell.

While all parties have a broadly similar structure, in the LDP's case the chairman of the General Council, the chairman of the Policy Research Council, and the secretary-general constitute a troika of top party officials who wield tremendous power over party affairs. Under LDP administrations, this troika had more power and a louder voice in many respects than the cabinet ministers who were the policy chiefs of the government. The three executives controlled policy decisions despite having no legal rights or responsibilities regarding government policymaking. As a result, when a government policy proposal conflicted with the ruling party's position, instead of the minister rallying the party around the government's proposal (or a report from a committee that would form the basis of a government proposal), the party's wishes were often given precedence.

In part 2 we will present reform proposals for rebuilding Japanese politics, bearing in mind the anomalous way in which Japan's parliamentary cabinet system has operated in the past, as described here.

The Japanese text of this article has been published by the independent, not-for-profit think tank Japan Initiative, of which the author is the president.

1 Until the consolidation of central government ministries and agencies under the reforms launched in 2001 by Ryutaro Hashimoto, acts of establishment did stipulate the powers of each ministry, but these were deleted following a proposal by Japan Initiative.