The Truth of the Annual Income Barrier and Current Pension System Distortions

February 21, 2024

R-2023-065E

With dual-income households on the rise in Japan, institutional barriers in taxation and social insurance that lead to a dependent spouse choosing to work less are widely discussed. Kazumasa Oguro, research director at the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research and professor at Hosei University examines the myths and realities of these barriers.

The “annual income barrier” (nenshu no kabe) is an expression in Japan. Although there is no precise definition, it is generally thought to refer to the “borderline of annual income” where a person within the range of being a dependent of a householder (for example, the wife as the spouse) working part-time or otherwise is excluded from being a dependent if she exceeds a certain annual income amount, resulting in a decrease (reversal) of her after-tax income due to the increased burden of taxes and social insurance premiums (Note 1).

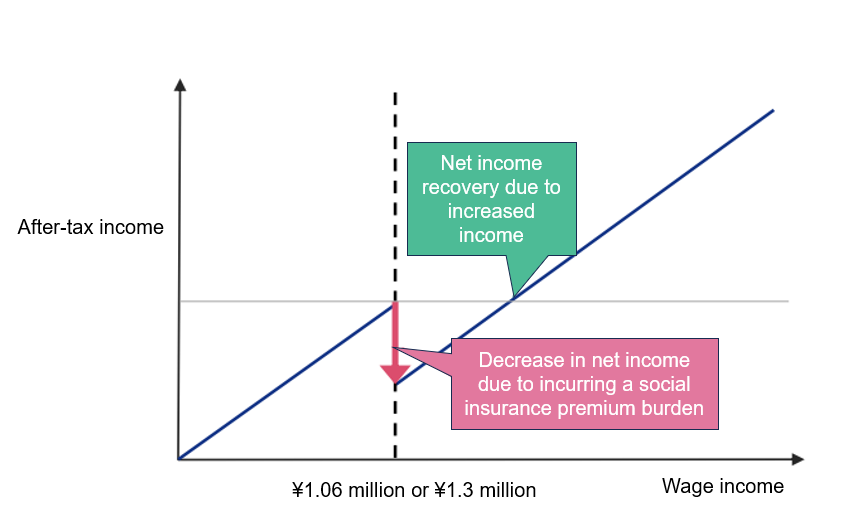

Figure: Image of the “annual income barrier” (Example: The case of incurring a social insurance premium burden)

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2023), “On the Annual Income Barrier and Support Enhancement Package”

Taking this problem into account, many housewives and others who work part-time make adjustments to their employment. As economic conditions change and more women work part-time or full-time, the majority of households are now not full-time homemaker households but dual-earner households. According to the “Labor Force Survey Special Survey” and “Labor Force Survey (Detailed Tabulation)” of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, the number of full-time homemaker households, which was 11.14 million in 1980, halved to 5.39 million in 2022, while the number of dual-income households, which was 6.14 million in 1980, doubled to 12.62 million in 2022.

Under such circumstances, Prime Minister Kishida’s demonstration of a desire to improve the “annual income barrier” suddenly drew attention to the issue on television, in newspapers, and in other media.

What, then, is the truth about the annual income barrier? “Annual income barriers” causing a stir on the Internet and elsewhere include: (1) the barrier of about ¥1 million; (2) the barrier of ¥1.03 million; (3) the barrier of about ¥1.06 million; (4) the barrier of ¥1.3 million; (5) the barrier of ¥1.5 million; and (6) the barrier of ¥2.016 million. However, there are also many misconceptions. Of these, it is a well-known fact among finance and tax system experts that what should really be called annual income barriers in terms of a decrease (reversal) in after-tax income are (3) and (4), while an annual income barrier basically does not exist in (1), (2), (5), and (6).

First, about the truth of (1): the barrier of about ¥1 million. About ¥1 million corresponds to the borderline of annual income subject to resident tax. There are two types of resident tax rates: per capita and income-based. Of these, the per capita rate generally differs according to the local government because it is affected by the municipality category, but the burden is generally incurred when one’s income exceeds about ¥930,000 to ¥1 million. However, since the burden of the per capita rate is a small amount of money per year (for example, ¥5,000 in the 23 wards of Tokyo and ¥5,500 in Ebino City, Miyazaki Prefecture), discussions on the resident tax barrier often pay attention to the income-based tax portion.

Resident tax (the income-based tax) is collected when one’s own income exceeds ¥1 million, which is the sum of the employment income deduction (¥550,000) and the basis of assessment for income-based resident tax (¥450,000). The tax rate is 4% for prefectural inhabitant tax and 6% for municipal inhabitant tax, for a total of 10% (in government-designated cities, 2% for prefectural inhabitant tax and 8% for municipal inhabitant tax, for a total of 10%). If various deductions such as the deduction for medical expenses are not applied, the income-based tax amount is calculated as 10% of the amount obtained by subtracting ¥980,000 (equal to the ¥550,000 employment income deduction plus the ¥430,000 basic deduction) from earned income earned through part-time and other work.

For example, if earned income increases by ¥10,000 from ¥1 million to ¥1.01 million, the income-based tax increases from zero to ¥3,000. It is clear from this formula that even if the burden increases by ¥3,000 in income-based tax, of the ¥10,000 increase in income, the after-tax income will increase by ¥7,000. Even after taking into account the per capita rate resident tax of ¥5,000, the after-tax income will increase by ¥2,000. As this example shows, if the definition of an annual income barrier refers to a decrease in after-tax income, then (1) the barrier of about ¥1 million does not exist (Note 2).

Next, about the truth of (2): the barrier of ¥1.03 million. Income of ¥1.03 million is equivalent to the borderline where income tax is incurred, and income tax may be collected if one’s income exceeds the sum of the employment income deduction (¥550,000) and the basic deduction (¥480,000). For example, if a spouse (wife) works part-time and her annual income exceeds ¥1.03 million, she may be removed from being a dependent of the householder (husband) and be subject to income tax herself. If various deductions such as the medical expense deduction are not applied, except for the employment income deduction and basic deduction, income tax is calculated as earned income minus ¥1.03 million (equal to the employment income deduction of ¥550,000 plus the basic deduction of ¥480,000) multiplied by the income tax rate. For example, if earned income increases by ¥10,000 from ¥1.03 million to ¥1.04 million, with an income tax rate of 5%, the income tax increases from zero to ¥500. Including the special income tax for reconstruction of 2.1% of income tax, ¥510 in tax is collected, but there is no annual income barrier in this sense either, as after-tax income increases by ¥9,490.

However, if the spouse’s (wife’s) earned income is less than ¥1.03 million, the householder (husband) can use the spousal deduction established in 1961, but if the spouse’s (wife’s) earned income exceeds ¥1.03 million, the spousal deduction will be zero. The tax burden on the householder (the husband) would increase, and his net income could decrease significantly. To address this problem, the special spousal deduction was enacted in 1967 to gradually reduce the spousal deduction when the householder’s (husband’s) annual income is less than a certain amount and the spouse’s (wife’s) earned income is between ¥1.03 million and ¥1.41 million. Until 2017, the special spousal deduction was structured such that it was reduced to zero if the spouse earned more than ¥1.41 million. However, starting in 2018, the special spousal deduction was reviewed, and the earned income of a claimable spouse’s earned income was raised to ¥1.5 million.

Under this review, the special spousal deduction was changed to a mechanism whereby the deduction was gradually reduced when the earned income of a spouse (wife) was between ¥1.5 million and ¥2.016 million. When the wife’s earned income exceeds ¥1.5 million, the deduction begins to shrink, and when it exceeds ¥2.016 million, the deduction is zero, so these situations are sometimes called the barrier of ¥1.5 million and the barrier of ¥2.016 million. These are barriers (5) and (6). If the wife’s earned income is ¥1.5 million or more, the special spousal deduction shrinks and the husband’s after-tax income decreases.

However, if the husband’s annual income is ¥10 million, the maximum income tax rate is 33%, and even if the wife’s earned income goes from ¥1.5 million to ¥2.02 million and the special spousal deduction of ¥380,000 becomes zero, the maximum decrease in the husband’s net income will be ¥125,000. Even if the husband’s net income decreases, if the wife’s earned income reaches ¥2.02 million, her net income will increase by about ¥420,000, and the couple’s combined after-tax income will increase by ¥300,000 or more. For this reason, if the judgment is based on the couple’s total net income rather than only the husband’s net income, then there is no annual income barrier for (5) and (6) either.

From the above, there is basically no institutional annual income barrier in (1), (2), (5), and (6), and the remaining possibilities are (3) and (4). Among them, (3) (the barrier of about ¥1.06 million) occurred due to the expansion of social insurance coverage (Health Insurance and Employees’ Pension Insurance) for part-time workers who meet certain conditions. I will explain this in sequence below.

First, basically, when a spouse’s (wife’s) wage income exceeds ¥1.3 million, she is no longer a dependent under the social insurance of the householder (husband), and the wife becomes obliged to take out social insurance herself. If the wife’s earned income is ¥1.31 million and she is over 40 years old, her standard monthly remuneration is ¥110,000, so the total annual health insurance premium burden, including the long-term care insurance premiums to be borne, is about ¥75,000. Since the total insurance premium burden of the Employees’ Pension is about ¥120,000 per year, the total burden of social insurance premiums, excluding unemployment insurance premiums, is about ¥200,000 per year.

If the wife’s annual income increased by ¥20,000 from ¥1.29 million to ¥1.31 million, which is an increase of about ¥200,000 in the burden of social insurance premiums from zero (i.e., covered by the husband’s social insurance), her after-tax income would decrease significantly. This annual income borderline is called the ¥1.3 million barrier, which is a real annual income barrier that exists institutionally (Note 3).

However, since 2016, (4) (the ¥1.3 million barrier) has been gradually breaking down. Attempts have been made to expand the coverage of social insurance (Health Insurance and Employees’ Pension Insurance) for short-term workers, such as part-time workers. Currently, social insurance is applied to short-term workers, such as part-time workers who (a) work at least 20 hours per week, (b) earn at least ¥88,000 in monthly wages, (c) are expected to be employed for at least two months, (d) are not students, and (e) work for a company with more than 100 employees (from October 2024, more than 50 employees).

Of these, since (b) wages of ¥88,000 is about ¥1.06 million per year, if the company for which the spouse (wife) works meets the above conditions, when the wife’s annual income (Note 4) is ¥1.06 million, she will be excluded from coverage under her husband’s social insurance and will pay her own social insurance premiums. If the wife’s earned income is ¥1.06 million and she is over 40 years old, her standard monthly remuneration is ¥88,000, so the total annual health insurance premium burden, including the long-term care insurance premiums to be borne, is about ¥60,000. Since the total insurance premium burden of the Employees’ Pension is about ¥96,000 per year, the total burden of social insurance premiums, excluding unemployment insurance premiums, is about ¥160,000 per year. If the wife’s annual income (Note 4) increased by ¥10,000 from ¥1.05 million to ¥1.06 million, which is an increase of about ¥160,000 in the burden of social insurance premiums from zero (i.e., covered by the husband’s social insurance), her after-tax income would decrease significantly. Therefore, the borderline of approximately ¥1.06 million is also a real annual income barrier that exists institutionally.

Based on the above, the annual income barriers that exist institutionally are (3) the barrier of about ¥1.06 million and (4) the barrier of ¥1.3 million. Of the annual income barriers that are causing a stir on the Internet and elsewhere, those that really exist institutionally are (3) and (4), which are problems (social insurance barriers) caused by the exclusion of dependents from the husband’s social insurance (Health Insurance and Employees’ Pension Insurance), and the annual income barriers (1), (2), (5), and (6) do not exist in the tax system.

The reason why some housewives adjust their employment with an annual income of ¥1.03 million related to (2) is that, depending on where the householder (husband) works, some companies provide a family allowance (spouse allowance), and there are cases where the certification criteria are set at a spouse’s (wife’s) annual income of ¥1.03 million or less (see National Personnel Authority (2022), etc.). According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2022) “2021 General Survey on Part-Time and Fixed-Term Workers,” 15.4% of women who adjusted their employment chose “Because we will no longer receive a spouse allowance from my spouse’s company if the amount exceeds a certain level.” If the family allowance (spouse allowance) provision conditions are a problem, the government should encourage companies to revise these conditions through a policy of some kind.

Is there, then, any way to eliminate (3) (the barrier of about ¥1.06 million) or (4) (the barrier of ¥1.3 million)? The reason this problem arises in the first place is that the moment a spouse’s (wife’s) annual income exceeds a certain amount (e.g., about ¥1.06 million or ¥1.3 million), she is no longer a dependent under the social insurance of the householder (husband) and becomes obliged to pay social insurance premiums herself. As already mentioned, the expansion of social insurance coverage for short-term workers has lowered the annual income barrier for some spouses (wives) working part-time from ¥1.3 million to about ¥1.06 million, but even at about ¥1.06 million, an annual income barrier exists to a certain extent.

One measure to eliminate this barrier is to lower and further ease condition (b), earning at least ¥88,000 in monthly wages, of the conditions for expanding social insurance coverage. For example, if condition (b) could be eased to earning at least ¥20,000 in monthly wages, the annual income barrier would be an annual income of ¥240,000, and even if a wife with an annual income of ¥250,000 were to pay social insurance premiums (Health Insurance and Employees’ Pension Insurance) herself, the total annual burden of social insurance premiums would be only about ¥35,000. In other words, even if the wife’s annual income increases from ¥240,000 to ¥250,000 and she is no longer a dependent under the social insurance of the householder (husband), her social insurance premium burden will increase from zero to only about ¥35,000 while her annual income increases by ¥10,000. Ultimately, if condition (b) could be eased to something like earning at least ¥1 in monthly wages, the annual income barrier could be virtually eliminated.

However, in relation to the current pension system, such a measure would create new inequities. The reason for this is simple, and is related to National Pension premiums. Firstly, the premiums for the National Pension are fixed at ¥16,520 per month (in FY2023). On the other hand, the premium rate for the Employees’ Pension is 18.3%. If a worker earning ¥88,000 in monthly wages (annual income of ¥1.06 million) is covered by the Employees’ Pension (a Category II insured person), the monthly burden of Employees’ Pension premiums is approximately ¥16,000 (total of worker and employer contributions), which roughly matches the premium level for the National Pension. For Category II insured persons, if they meet the requirements for payment, they can receive the second-tier earnings-related component (Employees’ Pension) in addition to the first-tier basic pension at the time of receiving pension benefits.

This means that those enrolled in the National Pension (Category I insured persons) can receive only the first-tier basic pension when they receive their pension even though they pay monthly premiums of ¥16,520, but a worker earning ¥88,000 per month can receive the second-tier earnings-related component (Employees’ Pension) in addition to the first-tier basic pension for roughly the same burden of premiums.

This current system alone is unfair, but if, for example, condition (b) is eased to at least ¥20,000 in monthly wages, the unfairness will increase even further. This is because when ¥20,000 in monthly wages is multiplied by the Employees’ Pension premium rate of 18.3%, the monthly Employees’ Pension premium burden is approximately ¥3,700 (total of worker and employer contributions), and this premium is about 20% of the National Pension insurance premium burden.

Those enrolled in the National Pension (Category I insured persons) can receive only the basic pension when they receive their pension even though they pay monthly premiums of ¥16,520, but a revision of the system that would allow a worker with ¥20,000 in monthly wages to receive the basic pension as well as the earnings-related component (Employees’ Pension) with a monthly insurance premium burden of approximately ¥3,700 would make the problems and distortions of the current pension system more serious.

This problem can be solved if there is a fundamental reform of the pension system, as outlined in my book Rebuilding the Japanese Economy (Nikkei Shimbun Publishing Co., Ltd.), but it would be difficult with minor revisions to the current system. As a stopgap measure, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced the “Annual Income Barrier and Support Enhancement Package” (Medical Insurance Subcommittee of the Social Security Council, held on September 29, 2023, Reference 4). The package deals with (1) the establishment of a career enhancement subsidy course (up to ¥500,000 per worker over three years) and (2) an allowance to promote social insurance coverage (a measure for a maximum of two years that applies to those whose standard monthly remuneration is ¥104,000 or less, involving exclusion from application of the standard remuneration calculation), which are related to Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s announcement that he would take measures to address the annual income barrier problem. However, this is a complicated system with a fixed deadline for the measures, and it is not an essential solution to the annual income barrier (about ¥1.06 million or ¥1.3 million). The solution requires fundamental reform of the pension system and other systems, and we hope to see deeper discussions on this in the future.

Note 1: When the relationship between (1) income before paying taxes and social insurance premiums and (2) after-tax income after paying taxes and social insurance premiums is plotted on a line graph consisting of line segments, there are areas where the line segments bend (kinks) and areas where the line segments disconnect (notches). In many cases, economic analysis considers both bends (kinks) and disconnections (notches), but this article deals with cases where net income decreases (reverses), which means that only disconnections (notches) will be considered.

Note 2: Taking into account the various benefit measures applicable to households exempt from resident tax and so on may increase the incentive to make work adjustments. For example, as Morinobu (2023) points out, the government’s uniform benefit of ¥30,000 for low-income households and separate benefit of ¥50,000 per child for households raising children as price measures are based on whether the household is exempt from resident tax, and if a household is exempt from resident tax and has two children, the benefit is ¥130,000 (¥30,000 plus ¥100,000), but if the household has even a small resident tax burden, it suddenly becomes zero.

Note 3: As noted by Shimazaki (2016), there is no legal basis for ¥1.3 million, and it is based on the notice “Regarding the certification of dependents for those with income” (April 6, 1977, Health Insurance Bureau Director’s Notice No. 9, Social Insurance Agency Director’s Notice No. 9) issued by the then Director General of the Health Insurance Bureau of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and Director of the Medical Insurance Department of the Social Insurance Agency. In addition, the part of the notice stating “¥1.3 million” was initially “¥700,000” (¥500,000 employment income deduction plus ¥200,000 spousal deduction) in relation to income tax (claimable spouse income limit) in the original 1977 notice. However, after 1987, it ceased to be linked to income tax, leaving the theoretical basis unclear to the present day.

Note 4: Strictly speaking, monthly wages of ¥88,000 refers to the scheduled wages (basic salary and other allowances). Therefore, unlike the dependent certification criteria of ¥1.3 million in annual income, the certification criteria of ¥88,000 per month (about ¥1.06 million per year) refers to an amount that does not include bonuses or overtime pay. In other words, it should be noted that about ¥1.06 million is not the annual income certification criteria.

References

- Kazumasa Oguro (2020), Rebuilding the Japanese Economy, Nikkei Shimbun Publishing Co., Ltd.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2022), “2021 General Survey on Part-Time and Fixed-Term Workers” https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/170-1/2021/index.html

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2023), “On the Annual Income Barrier and Support Enhancement Package” (Medical Insurance Subcommittee of the Social Security Council, held on September 29, 2023, Reference 4) https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12401000/001150869.pdf

- Kenji Shimazaki (2016), “The Concept of Dependent under the Health Insurance Law and its Application,” Journal of Social Security Research, Vol.1 No.3, pp.612-616.

- National Personnel Authority (2022), “2020 Survey of Remuneration in the Private Sector by Occupation” https://www.jinji.go.jp/kyuuyo/minn/minnhp/minR04_index.html

- Shigeki Morinobu (2023), “Making Work Pay for Japanese Women: Toward a Smarter Approach to Tax and Social Security Reform,” The Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, Review article X-2023-002E https://www.tokyofoundation.org/research/detail.php?id=946