- Article

- Tax & Social Security Reform

The False Promise of Reduced Consumption-Tax Rates: A Plea for Targeted Credits

April 11, 2016

The government’s plan to exempt food and drink from the consumption-tax hike scheduled for April 2017 is a serious mistake, writes tax expert Shigeki Morinobu. In an essay based on his expert testimony before the lower house Committee on Financial Affairs, Morinobu exposes the false allure of reduced rates and makes the case for refundable tax credits as a cheaper and more effective means of helping low-income households.

* * *

The government of Shinzo Abe has announced plans to apply a reduced tax rate to food and drink when the national consumption tax is raised from 8% to 10% in April 2017. The idea is to maintain the current 8% rate for foodstuffs, excluding meals eaten out and alcoholic beverages, to cushion the impact of the tax increase on low-income families.

While the aim of offsetting the regressive impact of the consumption tax is laudable, the adoption of special reduced rates for specific goods is bad policy. I recommend dropping this expensive and ill-considered break and replacing it with a refundable tax credit targeted to the households most in need of support.

Redistribution in Favor of the Wealthy

Why are reduced consumption-tax rates such a bad idea?

First, lower rates on food purchases will not serve the purpose of redistributing income to address economic inequalities. To begin with, the tax break is not targeted to low-income households, since it actually grows as one goes up the income ladder. In addition, to help offset the projected 1 trillion shortfall resulting from the reduced rates, the government is scrapping a new social security policy that would have benefited low-income households by setting a ceiling on their payments of total healthcare and childcare costs. Ultimately, the new policy is unlikely to lead to the redistribution of income and is incongruous with the integrated tax and social security reform plan approved in 2012.

The second problem is that the application of reduced rates ultimately imposes a higher burden across the board by increasing the complexity and cost of tax collection. Compared with income taxes, which depend on the self-reporting of expenses to calculate taxable income, consumption taxes tend to be straightforward and inexpensive to administer; this is one of their major advantages. But once multiple rates enter the picture, businesses are obliged to keep separate books for different categories of goods and services, and the added cost is passed on to the consumer. This complexity also increases the cost of administration and enforcement by the tax authorities.

In European countries that apply a reduced value-added tax rate to food purchases, problems have arisen over the distinction between take-out and eat-in restaurant meals, and one can easily imagine similar issues emerging here in Japan. The complexity of a system with multiple tax rates also facilitates tax evasion and fraud, leading to further loss of tax revenue. Ultimately, it is the nation as a whole that pays the cost.

The third problem with reduced rates is that they create an incentive for intensive lobbying by industries and other interests, opening the door to political corruption. Already the healthcare and housing industries are trying to mobilize public opinion in favor of further expansion of lower rates. In Europe, political parties have incorporated reduced tax rates into their election platforms to drum up campaign support. Not so long ago, corporations and industry groups vied for preferential legislative and administrative treatment; reduced rates could take us back to the bad old days of rampant collusion, influence peddling, and pork-barrel politics.

In April 2014, tax authorities from the world’s leading industrial nations gathered in Tokyo for the second meeting of the Global Forum on VAT of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. One of the topics of discussion at that meeting was the inefficiency of reduced rates from the standpoint of tax policy. Experts from the OECD Secretariat and the IMF urged governments to limit the application of reduced rates and zero rates as much as possible, arguing that such consumption-tax (or value-added tax) breaks are an extremely ineffective means of providing relief to low-income households. The consensus of the meeting was summed up as follows in an April 18 press release: “Countries often implement reduced rates to alleviate the burden on poorer households, but discussions at the Forum confirmed that this is a very expensive way of providing support to the poor, particularly when compared to the use of targeted cash transfers.”

This view was underscored by Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the OECD’s Center for Tax Policy and Administration, in a conversation with the author. His advice on the subject of reduced rates was clear and unambiguous: “Don’t follow Europe.”

Dangling the Lure of Tax Cuts

To my mind, the most troubling aspect of the recent decision to adopt reduced rates was the government’s failure to explain to the public its plans for financing them. It seems to me that the ruling coalition is treating the voters with disdain by dangling the prospect of a tax break in the form of reduced rates while delaying any serious discussion of offsetting the revenue shortfall until after the House of Councillors election this summer.

Japan’s consumption tax is levied for the express purpose of fully financing the nation’s social security system. If rates are to be cut for some items, it follows that they need to be raised for others. A rational plan for a 1 trillion exemption for certain goods should also include an increase in the standard rate sufficient to offset the loss of revenue. According to my own rough calculations, this would mean bumping up the standard consumption tax from the planned 10% to 10.5%. Why not let the public choose between a flat 10% rate and a 10.5% standard rate with an 8% reduced rate—while simultaneously discussing the merits of a refundable tax credit as an alternative for providing tax relief for the poor?

Unfortunately, the only choice the people were offered this time around was between reduced rates and no reduced rates. And given a simple choice between lower and higher taxes, people will naturally choose the former.

The media must bear part of the blame for the simplistic content of the debate. Given that newspaper publishers were vigorously lobbying the ruling coalition for a reduced rate themselves, the press’s inadequate coverage of the issue—including its failure to provide opportunities to debate the pluses and minuses of a refundable tax credit—has struck some as a case of biased reporting. Let us hope that the papers do not leave themselves open to such charges in the future.

Merits of a Refundable Tax Credit

The failure to seriously consider a refundable tax credit is particularly perplexing given that the 2012 legislation revising the consumption tax calls for just such a system as an anti-regressive measure to alleviate the burden on low-income households. In the following, I would like to outline a concrete proposal for a refundable tax credit.

My inspiration is Canada’s GST/HST credit, under which households with low or modest incomes receive quarterly payments intended to offset all or part of the goods and services tax (GST) that they pay. The payments are adjusted according to the family’s net income, but for those making less than the threshold of $35,465, the basic credit is $272 per adult and $143 per child. Taxpayers who wish to apply for the GST credit need only indicate that option on their tax returns. The tax agency then determines eligibility and the amount of the credit on the basis of the family income and makeup and deposits it directly in the taxpayer’s bank account. This simple, user-friendly system minimizes the potential for fraud. In fact, Japan already has a similar system in place for an income-based child allowance, and the same infrastructure could be used for the refundable tax credit. Under Japan’s new taxpayer number system, which was introduced in January this year, it would be a simple matter to calculate such a credit on the basis of net household income. The central government would design the system, with administration being carried out at the local level.

The Canadian tax system has another feature worth emulating, namely, the Working Income Tax Benefit. This cash benefit is available only to low-income households with earned income, and it increases with each dollar earned above base income (up to a certain ceiling), thus incentivizing work. In other words, the WITB is specifically targeted to the problem of the working poor. By adopting similar tax credits in Japan, we could not only offset the regressive nature of the consumption tax but also provide much-needed support to this country’s working poor, particularly the swelling ranks of nonregular employees.

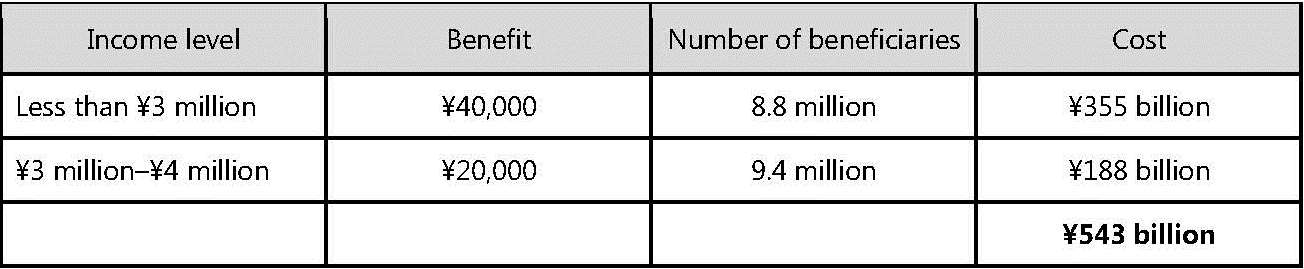

Using the Canadian system for reference, I compiled the following table tentatively indicating the amount of the proposed credit and the estimated cost under a comparable system in Japan.

Amounts and Cost of Proposed Refundable Credits (rough calculation)

Here I have posited a system under which households with annual income of less than 3 million yen would receive 40,000 per member (adults and children) in benefits, while those making 3 million to 4 million would receive 20,000 per member. As a consumption-tax rebate, this would make the ratio of tax paid to income roughly the same for lower-income households as for middle-income households. (Those receiving public assistance or old-age pensions would not be eligible for credits, as cost-of-living increases would be incorporated in these benefits.) The total projected cost of the tax credit would be around 540 billion, as compared with the 1 trillion lost by the application of reduced rates (8%) to food and drink.

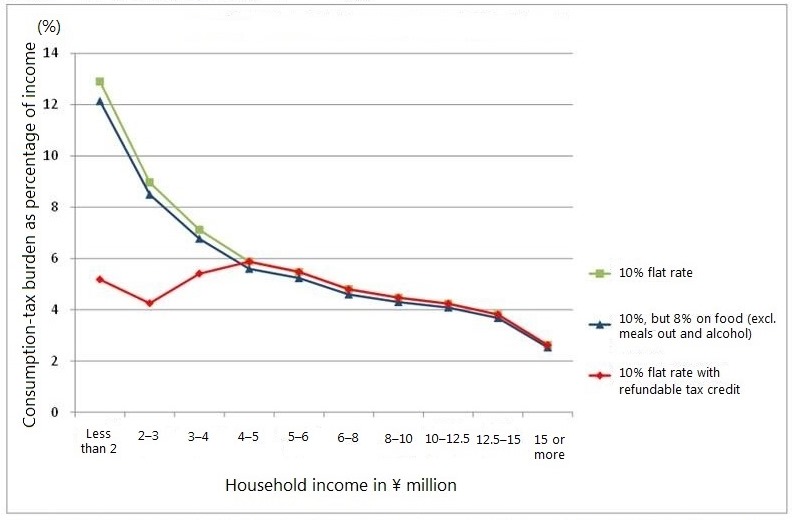

But what about the impact on household finances? The figure below charts the effective burden of the consumption tax (as a percentage of income) on a family of three at each income level under three scenarios: a flat 10% consumption tax, a 10% standard rate with an 8% rate for food and beverages, and a 10% rate accompanied by the refundable tax credit outlined above.

Comparison of Tax Burden on Three-Member Households by Income Level (married couple and one child)

As the chart indicates, the consumption tax hits lower-income families the hardest, but the reduced rate proposed by the government barely mitigates the regressive nature of the tax. However, the refundable tax credit turns this regressive burden into a progressive one, substantially easing the relative impact on low-income households.

Turn Back Now

The 1 trillion that the reduced rate would cost the government could finance not only the aforementioned tax credit but also an earned income tax credit to support the working poor, including the growing ranks of employees in nonregular formats. In the process, it could also address the problem of the “1.3 million yen ceiling” that discourages married women from taking full-time positions out of pension-premium payment considerations.

Japan is facing ever more daunting economic challenges. Even with the government focusing its full attention on the domestic economy, business performance is flagging under the impact of China’s economic slowdown and the stronger yen. Abenomics, Prime Minister Abe’s vaunted economic revitalization policy, is in danger of coming unraveled.

To meet these challenges and shore up the foundations of the Japanese economy, the government must shift its policy focus from the elderly to the younger, working population. It must channel serious fiscal resources into measures to boost the fertility rate, while taking decisive action to address the problem of the working poor stemming from the expansion of nonregular employment. Japan is virtually the only advanced industrial country today that has no consistent policy in place to support the so-called working poor.

The adoption of reduced consumption-tax rates is a counterproductive policy fraught with problems. The government should scrap this ill-conceived plan and begin deliberations on the adoption of a refundable tax credit.

Based on the author’s February 29, 2016, presentation to the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Affairs.