- Article

- American Politics

US Engagement Policy toward China: Realism, Liberalism, and Pragmatism (1)

January 30, 2014

US policy toward Beijing has consistently been one of engagement since President Richard Nixon’s visit to the People’s Republic of China in 1972. There have been occasional swings in nuance, though, resulting from the positioning of four groups within the United States—pro-China commercial liberals, anti-China human-rights-oriented liberals, pro-China interdependence- and stability-focused realists, and anti-China military- and rivalry-focused realists—frustrating China and US allies in the region. In addition, US policy has been shaped by two distinct schools sharing the balance-of-power concept within the realist paradigm: one, which grew around Henry Kissinger, is optimistic about China’s future trajectory, while the other is skeptical. Despite the subtle but perceptible swings over the years, US leaders have managed to balance the various domestic interests and ideologies into a pragmatic and feasible policy, which has largely remained within the engagement paradigm. This paper examines whether or not US policy toward China is currently undergoing a structural change due to several key developments in recent years and the Obama administration’s evolving perceptions of China. (This article is reprinted with permission from The Journal of Contemporary China Studies , Vol. 2, No. 2, published by the Institute of Contemporary Chinese Studies, Waseda University .)

Introduction

In 2009 Barack Obama began his presidency with the “audacity of hope” that China would become a responsible stakeholder, cooperating with the United States on various global issues from climate change to post-Lehman financial and economic crisis management through the framework of a US-China “Group of Two.” By the following year, though, China’s assertiveness on territorial issues in the South and East China Sea and the harsh reaction to US arms sales to Taiwan dampened US optimism regarding China as a global partner. Despite mounting frustration, the Obama administration patiently maintained close bilateral communication, such as through the US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, as part of its engagement policy toward China.

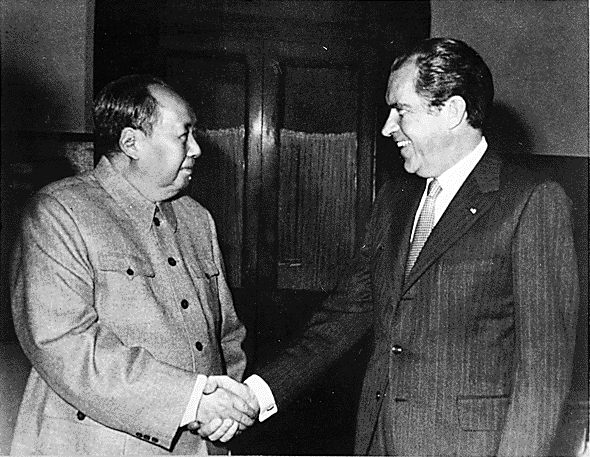

Since President Richard Nixon’s surprise visit to the People’s Republic of China in 1972, the US policy toward Beijing has consistently been one of engagement, in sharp contrast to the antagonistic containment policy from 1947 to 1972 during the first half of the Cold War.

That said, there have been subtle changes in the substance of the US engagement policy over the years. These occasional policy swings in the US government have frustrated China and US allies in the region. US journalist James Mann describes the occasional “about face” moments in US policy from the Nixon to the Bill Clinton administrations in his book, About Face. [1]

For example, during the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton criticized President George H.W. Bush for irresponsibly extending most-favored-nation (MFN) status to China without considering the country’s human rights violations in the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident. The Clinton camp proposed a linkage policy between improvements in human rights and MFN status. When he was elected president, however, Clinton ignored his campaign proposal and extended MFN status before there was any tangible improvement in the human rights situation. Clinton even called on Congress to grant China permanent MFN status in 2000 (the designation was renamed “permanent normal trade relations” in 1998) without considering human rights, as the prosperous business and economic relations with China was contributing to a booming US economy.

During the 2000 presidential campaign, George W. Bush criticized Clinton’s strategic partnership with China and proposed that the country be redefined as a strategic competitor. [2] US-China relations deteriorated following the accidental collision between a US Navy EP-3E signals intelligence aircraft and a People’s Liberation Army Navy J-8II jet fighter near Hainan Island in April 2001. The terrorist attacks on September 11 of that year, though, restored the cooperative tone of US-China relations. In his visit to Beijing in February 2002, President Bush welcomed China’s cooperation on the global war on terror following 9/11. [3]

Despite such policy swings, all US administrations since 1972 have remained within the engagement paradigm. Initially, this paradigm was shaped by the Cold War dynamics of the global balance of power. In the post–Cold War period, though, China has emerged as a potential challenger to the regional and even global hegemony of the United States. In this context, the mutual interdependence of the US and Chinese economies has become a tool to justify the engagement paradigm as serving both economic and security interests.

For Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, China was regarded as a positive game changer that could break the quagmire of the Vietnam War and the impasse in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Hence, strategic cooperation with China was a crucial factor in the US Cold War strategy, enabling Washington to strike a balance with its strategic adversary between 1972 and 1989. Kissinger himself pointed out that China no longer sought to constrain US power projection and started enlisting the United States as a counterweight against the Soviet Union. [4]

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many US security experts began to see China, with its growing power, as a potential rival to US regional and global hegemony, although Kissinger and his school retained their expectations that the US-China partnership would continue to grow. Two different schools thus shared the balance of power concept within the realist paradigm. Their differences were policy implications: While the Kissinger school was optimistic about China’s future trajectory, the other school was skeptical.

A new dimension to the US engagement paradigm was added after the end of the Cold War in the face of rising economic and commercial expectations regarding the burgeoning Chinese economy. Now positioned as the second largest in the world, China’s rapidly growing economy has become essential for US businesses. Deepening US-China economic interdependence is regarded as a factor in preventing an eventual US-China hegemonic rivalry, and liberal politicians have come to endorse an engagement policy, rather than the realism they espoused during the Cold War.

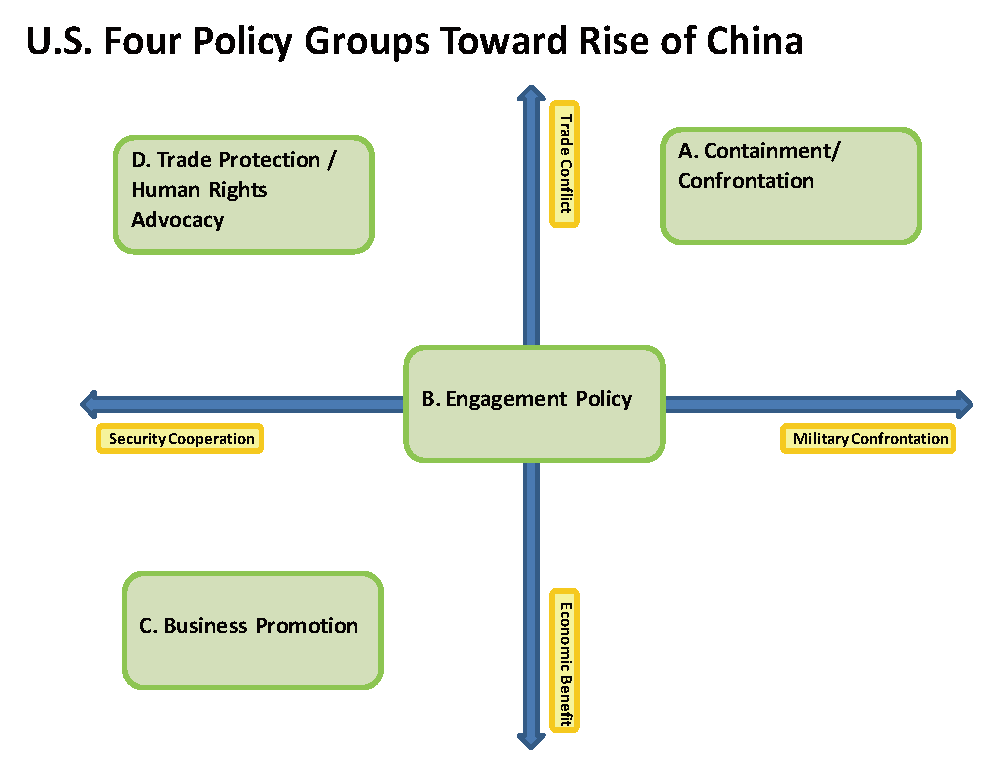

Schizophrenic tendencies in the US policy toward China can be seen in the shifting policy focus of US administrations, alternating between realism and liberalism. The US posture toward China has been affected by the positioning of various domestic actors, such as pro-China commercial liberals, anti-China human-rights-oriented liberals, pro-China interdependence- and stability-focused realists, and anti-China military- and rivalry-focused realists.

Competition among the various policy schools became more visible and significant with each US presidential election cycle. Despite the policy swings and contradictory approaches, though, US leaders have managed to balance the various domestic interests and ideologies into pragmatic and feasible policies. In this sense, pragmatism has always been a dominant trait of US leaders, and US policy toward China since 1972 has, as a result, largely remained within the engagement policy paradigm despite vociferous arguments from both the left and right. At the same time, the pragmatic approach of US administrations has always provided a ready target for criticism from their political rivals.

Barack Obama is probably one of the most pragmatic presidents in US history. Unlike Clinton and Bush Jr., Obama began his administration without criticizing the China policy of his predecessor, although he did have harsh criticism for the decision to start the Iraq War. Over time, Obama’s China policy came to be shaped more by China’s assertiveness and uncooperative attitude toward global governance. Being a pragmatist, Obama shifted his China policy from one of cooperative engagement to cautious engagement in order to hedge against China’s military expansion and its assertive behavior toward its neighbors.

Does Obama’s policy shift signal a historic transition from an engagement to a containment paradigm, with the United States perceiving drastic changes in the balance of power in the twenty-first century? Or is this just the latest of the periodic swings within the engagement paradigm that we have observed since 1972? This paper examines whether or not US policy toward China is undergoing structural change by focusing on several key factors that have shaped the policy over the years.

1. Four Different Policy Groups

The apparent schizophrenia in US attitudes toward China can be explained by the existence of four distinct camps that have exerted an influence on US administrations. Winning a US presidential election requires candidates to secure the support of a broad array of constituents. One group may be critical of China’s human rights record, while another might seek stable business ties. The candidate must navigate carefully between the two different orientations, and, as a result, the policies they outline are often vague.

The four major camps influencing the direction of US policy toward China are outlined in the Figure 1. The four blocs (A to D) are identified with regard to policy directions, particularly in security and trade.

Group A represents the hawks who believe that hegemonic rivalry and military collision is likely, as a rising China increasingly poses a challenge to the United States both regionally and globally. This group is not optimistic that China would become more democratic as its economic grows, and it is also skeptical about economic interdependence acting to stabilize the relationship and preventing conflicts. It thus advocates a confrontational security policy toward China bordering on containment.

A group called the Blue Team in the George W. Bush administration, for instance, adhered to an anti-China security policy. Many members were neoconservatives who advocated the use of US military power to promote democratization around the world. Blue Team members saw China’s Marxist, one- party rule as a potential source of confrontation. And they did not expect China to democratize on its own as a natural outcome of economic growth.

Vice-President Richard Cheney was among the leading figures in this group. Princeton University Professor Aaron Friedberg, who served as Cheney’s national security advisor, provided theoretical support for the confrontational policy, arguing that China was a game changer for the international system. [5] Friedberg believed that China’s growing wealth and power would, if its one-party, authoritarian dictatorship was left intact, become a source of tension with the United States. [6]

In 2000, conservative, anti-China members of Congress created the US- China Economic and Security Review Commission with a mandate “to monitor, investigate and submit to Congress an annual report on the national security implication of the bilateral trade and economic relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, and to provide recommendations, where appropriate, to Congress for legislative and administrative action.” [7] In its annual report to Congress in 2012, the commission made 32 policy recommendations to the Obama administration, including a review of investments in the United States by Chinese state-owned and state-controlled companies, flows of military technology or data to China, and China’s cyber practices. [8]

Group B represents those with moderate and pragmatic positions who advocate maintaining the engagement policy. Most policy practitioners since Nixon’s 1972 visit to China belong to this group. Even within this camp, though, there are subtle differences in policy orientation. Those advocating soft engagement in such forms as a “sunshine policy” argue that economic cooperation would encourage China to be a benign and helpful partner in the security and political arenas. This position is close to group C, which emphasizes mutual economic interests and interdependence. On the other hand, the hard-line, “hawkish” engagement proponents attach importance to hedging against a potential military confrontation with China. This position is close to group A, with an emphasis on the hedge element.

The softer position is championed by those viewing China as a stakeholder or envisioning a US-China G2. In general, they are optimistic about China’s cooperative attitude in the region and the world. Robert Zoellick, deputy secretary of state in the George W. Bush administration, advocated a “stakeholder” policy in a 2005 speech in which he said that China was unlike the Soviet Union of the late 1940s in four ways. First, China does not seek to spread radical, anti-American ideologies. Second, China does not seek conflict against democracy, although it is not itself a democracy. Third, China is not opposed to capitalism. And fourth, China does not seek to overturn the fundamental order of the international system but rather believes that its success depends on being networked with the modern world. [9]

Zbigniew Bzrezinski, former national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter who advanced the normalization process with China in 1979, was a notable advocate of the G2 position.

Bzrezinski was a strategic thinker in the realism school who saw a globally ascending China as a revisionist force for important changes in the international system. He felt that China would seek them in a patient, prudent, and peaceful manner and noted that Americans who deal with foreign affairs appreciate China’s “peaceful rising” in global influence while seeking a “harmonious world.” [10] Bzrezinski has influenced the Obama administration through his advice on foreign and security policy.

Unlike Zoellick and Bzrezinski, the hawkish engagement position is skeptical of China’s self-described “peaceful rise.” For example, bureaucrats in the Department of Defense are concerned about China’s modernizing military and growing global economic influence. Unlike those in group A, they tend to be neutral about China’s Marxist ideology or one-party authoritarian rule. In other words, they do not necessarily believe that military confrontation with China is inevitable. But at the same time, they do not share the notion that economic interdependence in itself would help prevent military confrontation. Andrew Marshall, who has continued to serve as director of the Department of Defense’s Office of Net Assessment since being appointed by President Nixon in 1973, is one of the leading hawk engagers in this group. His perceptions of China can be gleaned from various Department of Defense reports, including the 2012 annual report to Congress. The report observes that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) pursues a long-term, comprehensive military modernization program to win “local wars under conditions of informatization,” or high-intensity, information-centric regional military operations of short duration. On the other hand, the report says that Chinese leaders seek to maintain peace and stability along their country’s periphery to secure access to markets, capital, and resources and avoid direct confrontation with the United States and others. The report recommends strengthening the US-China military-to-military relationship by encouraging it to cooperate with the United States and others through cooperative practices to secure access to international public goods through counter-piracy or international peacekeeping operations. [11] These two different approaches to the rise of China within the B camp will be discussed in the following section.

Those in the C group espouse a more optimistic view that deepening economic ties would prompt China to become a more cooperative actor in the region and the world. They have less concern about China’s rapid military expansion and modernization resulting from accumulating wealth. They represent the economic interests of industry and business that stand to reap benefits from enhanced trade and investment. They tend to be quiet about advocating their positions, though, because they are wary of being criticized for their “greedy” pursuit of business interests or ignorance of US national interests and China’s human rights record. As the result, few government officials openly take this position. However, advocates exert considerable influence among both Republican and Democratic party leaders and administrations through their financial donations.

Henry Paulson, who was treasury secretary in the George W. Bush administration, is one of the group’s few visible policy advocates. He built a close network with Chinese counterparts during a financial career at Goldman Sachs and was a founding member of the US-China Strategic Economic Dialogue, which was upgraded to US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in 2009. As treasury secretary, Paulson believed that robust and sustained economic growth was a social imperative for China and that Chinese leaders viewed the country’s international relations primarily through an economic lens. Paulson thus proposed approaching China through economic interests as “an effective way to produce tangible results in both economic and noneconomic areas.” While noting that some people were recommending containment, Paulson clearly stated that engagement was “the only path to success.” [12]

Those in group D represent the liberal Democratic in Congress who are concerned about promoting human rights and protecting American jobs in the face of China’s currency manipulation and closed market. Human rights watchers include former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who early in her congressional career worked to protect Chinese students in the United States in the wake of the Tiananmen Square incident. She co-sponsored and helped pass legislation to extend the length of stay of the students, who could have been arrested once back in China for their support of the 1989 pro-democracy movement. Pelosi continued to promote actions against human rights violations even while serving as House speaker and currently House minority leader. On her website, Pelosi states, “in China and Tibet, people are languishing in prisons for only expressing their ideas and political views.” She adds that Nobel Peace Prize recipient Liu Xiaobo, who called for an online petition to promote human rights and democracy, is still in prison and argues, “If we don’t stand up for human rights in China and Tibet then we lose our moral authority to speak out for human rights in the rest of the world.” [13]

The trade protectionist wing within group D is represented by Senator Chuck Schumer. He has sponsored many retaliatory bills against China, such as higher tariffs in response to “currency manipulation,” which is blamed for eating into US domestic employment. For example, Schumer co-sponsored the Currency Exchange Rate Oversight Reform Act of 2011 to impose tariffs on imports from countries with undervalued currencies. Although the bill was approved by the Senate on 11 October 2011, it was rejected by the House.

On his website, Schumer takes a negative view of China’s participation in the WTO, which was expected to bring China’s policy in line with global trade rules. Instead, he claims, China has used those rules to spur its own economic growth and expand exports at the expense of its trading partners, including the United States. He also criticizes “China’s overt and continuous manipulation of its currency to gain a trade advantage over its trading partners.” [14]

D group members cooperate with group A Republicans on human rights and trade issues at the congressional US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. In fact, the commission’s chair has alternated between representatives of the two groups. For example, the current chairman during the reporting cycle through December 2013 is William Reinsch, a Democrat who served as legislative assistant to Senator John Rockefeller. The current vice-chairman and former chairman is Dennis C. Shea, who served as assistant secretary in the Department of Housing and Urban Development during Republican George W. Bush’s administration. [15]

Figure 1: Two Influential Schools in the Realism Tradition

The US engagement policy toward China since 1972 has been conducted mainly by realists in both Republican and Democrat administrations. In 1972, President Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, led a drastic policy paradigm shift from the confrontational containment policy of previous administrations to one seeking cooperation with China. It also represented a shift from an ideology-oriented containment policy against the Communist bloc as a whole toward a calculated engagement policy based on balance-of-power realism. Nixon understood the necessity of cooperating with China to influence the balance of the power in favor of the US strategic position against the Soviet challenge, in spite of ideological differences with China. Ironically, China’s Marxist ideology was more radical than that of the Soviet Union. In fact, China criticized the Soviet position as revisionist and for straying from Marxist ideals.

[1] James Mann, About Face: A History of America’s Curious Relationship with China, from Nixon to Clinton (New York: Vintage Books, 2000).

[2] Condoleezza Rice, “Promoting the National Interest,” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2000 (vol. 79, no. 1).

[3] “President Bush Meets with Chinese President Jiang Zemin,” February 21, 2002, US Department of State Archive, http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rm/2002/8564.htm (accessed March 23, 2013).

[4] Henry Kissinger, On China (New York: Penguin Press, 2011): 275–76.

[5] Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011).

[6] Yoichi Kato, “Interview/Aaron Friedberg: More Balancing Needed than Engagement with China,” The Asahi Shimbun (September 13, 2012), http://ajw.asahi.com/article/views/opinion/AJ201209130026 (accessed March 24, 2013).

[7] US-China Economic and Security Review Commission website, http://www.uscc.gov/ (accessed March 24, 2013).

[8] US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “2012 Report to Congress: Executive Summary and Recommendations,” November 2012, http://origin.www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/annual_reports/2012-Report-to-Congress-Executive%20Summary.pdf(accessed March 24, 2013).

[9] Robert Zoellick, “Whither China: From Membership to Responsibility?” Remarks to the National Committee on US-China Relations, September 21, 2005 at http://2001-2009.state.gov/s/d/former/zoellick/rem/53682.htm (accessed March 24, 2013).

[10] Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The Group of Two that Could Change the World,” Financial Times, January 13, 2009.

[11] Office of the US Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China 2012, May 2012 at http://www. defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/2012_CMPR_Final.pdf (accessed March 24, 2013).

[12] Henry Paulson, “A Strategic Economic Engagement: Strengthening US-China Ties,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2008.

[13] Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi’s website, http://pelosi.house.gov/special-issues/human-rights.shtml (accessed March 24, 2013).

[14] Senator Charles E. Schumer’s website, http://www.schumer.senate.gov/Issues/trade.htm (accessed March 24, 2013).

[15] US-China Economic and Security Review Commission website, note 7.