Refundable Tax Credits: The Better Choice

A number of developed Western nations have had great success with the introduction of a system of refundable tax credits aimed at providing economic support to lower- and middle-income taxpayers. Let me explain this system simply in terms of the proposed ¥2 trillion outlay for Japan's cash handouts. Divided equally among the roughly 10 million dependents aged 15 or younger in households with less than ¥6 million in annual income, this would come out to ¥200,000 per head, to be distributed to the households where those dependents live. A family with two eligible children would receive a credit of ¥400,000. If that family's tax bill for the year was higher than this amount, it would be deducted from the taxes due; if the tax bill was lower, or if the family's income was below the taxation threshold, the family would receive the difference, which makes the credits "refundable." This is an effective, efficient approach that combines the taxation and social security systems to achieve the same income-redistribution goals that they do, and it is in broad use in the other developed nations of the world.

The refundable tax credit systems in place in Western nations can be placed in four categories according to their policy aims.

The first of these is earned income tax credit (EITC) systems. These credits are granted in defined amounts to lower- to middle-income households where the taxpayers have worked at least a minimum number of hours. This system aims to prevent the moral hazard of the situation where it makes more economic sense to rely entirely on welfare benefits and to keep people from falling into the poverty trap. It is meant to encourage people's efforts to improve their job skills and live more self-reliant lives, and as such it is often implemented in concert with jobs training and education programs.

The second category is child tax credit (CTC) systems. These provide credits to households with children, with the amount increasing along with the number of minors. This approach helps to prevent poverty among single-parent households and to provide child-rearing support; in these ways it serves as a measure to counter dwindling birthrates as well.

Systems in the above two categories saw expanded use in Britain under Prime Minister Tony Blair and in the United States under President Bill Clinton. Based on the concept of "workfare," which helps people attain self-sufficiency through work, they are today fundamental parts of the UK and US taxation systems.

The third category is tax credits to offset social insurance costs. Here the aim is to reduce the burden on those in lower income brackets of taxation and social contributions. The Netherlands and South Korea have introduced systems along these lines, although the Dutch system merely offsets the contributions required of lower-income taxpayers and involves no rebates to them.

In the fourth category are tax credits to offset consumption tax liabilities. Such systems are in place in Canada and Singapore to reduce the regressive impact of consumption tax hikes on people in lower income brackets. They involve deductions and refunds of liabilities for consumption tax on basic necessities from the income tax amount. This approach is far more effective than straightforward tax rate reductions in countering the regressive nature of taxation.

Approaches in these categories have recently come to be viewed as potentially beneficial for Japan as well. The government's Tax Commission clearly stated in its recommendation report on tax reform for fiscal 2008 that exploring these options would be a meaningful task for Japan, as many nations were making use of these systems to provide "assistance to low-income people, particularly among the younger generations, childrearing assistance, employment assistance, and an approach to offset the regressivity of consumption tax. Some countries take the tax and social security regimes as a whole and use refundable tax credits to lessen the social insurance premium burden."

Two Issues to Tackle

There are a number of challenges to overcome if a refundable tax credit system is to be introduced in Japan. Below I examine two of the major challenges in detail.

The first of these is the need to create a framework for managing the system. In all the nations that offer refundable tax credits, a single taxation authority handles both the tax reductions and the provision of benefits. People who fall below the minimum income threshold apply directly to the tax authority for inclusion in the system and receive their benefits from that same authority after an examination of their situation. For salaried workers, it would be quite possible to follow the example of Britain when it first introduced its system and have their employers handle the necessary calculations in the year-end adjustment of payment records for taxation purposes.

The problem with this approach is that to include the self-employed in the system, the state must get an accurate picture of their income levels. The Japanese expression kuroyon , or "nine-six-four" taxation, expresses the difficulty faced here: the authorities are said to be able to monitor some nine-tenths of salaried workers' income, but just six-tenths of that of the self-employed and four-tenths of what farmers make. This leads to varying accuracy in assessing the incomes of those who make salaries and others, giving rise to unfairness in the system. Another problem is that calculating income on a household basis will require considerable extra work to square the current individual tax filing system. Overcoming these issues may require the introduction of a system of taxpayer identification numbers.

A November 2008 report issued by the National Commission on Social Security called for consideration of the introduction of a system of social security numbers. Giving each citizen a number for life would allow the centralized management of personal information connected with social security schemes, thus clarifying the balance between pension, medical care, and nursing care benefits and obligations. Ever since the governmental Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy recommended such a system in its 2006 Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Structural Reform, deliberations have moved forward with the goal of implementing social security numbers in fiscal 2011 (April 2011-March 2012). Japan could use these numbers for taxpayer identification as well, framing them not merely as a tool to facilitate tax collection but also as a means of identifying taxpayers so that they can receive benefits under the refundable tax credit system.

The second issue that must be faced is the need to fundamentally rearrange and unify the disparate systems now in place for social security and taxation in Japan, creating a new framework to bring these tasks all together. We will need to reexamine from the ground up a whole raft of the country's present systems-including child benefits and childcare allowances, welfare and other benefit systems, basic income reductions, for spouses and the like, and minimum-wage regulations-as we design this framework.

At its November 12, 2008, meeting, the pensions subcommittee of the Social Security Council listed eight areas of focus for reform of Japan's pension systems. Topping the list was a recommendation for the creation of a system to lower insurance fees as a way to offer relief to people with low incomes or receiving scant pension benefits. The approach of using public funds to help people in low-paying jobs meet the required level of pension payments is one that matches the Dutch and Korean systems of refundable tax credits to offset social insurance costs outlined above. In the Dutch version, the high insurance (payroll tax) payments made by low-income individuals are deducted from their income taxes, thereby reducing their overall burden. The system is designed so that the amount deducted climbs along with their income, however: the more they work the more they can reduce this burden, thus providing them with an incentive to work harder. This approach is considerably less likely to produce a moral hazard than the straightforward insurance fee reduction system being considered by the Japanese government council, and is naturally a better choice from the perspective of making effective use of public funds.

Needed in Kasumigaseki: Creativity and Decisiveness

Strong political leadership will be a must in implementing policy on this scale. In the administrative system in place today in Japan, tasks are divided among multiple entities, with the Ministry of Finance in charge of taxation and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in charge of social security matters. As things now stand it is nearly impossible to execute policy that goes beyond these narrow fiefdoms. The introduction of refundable tax credits, involving as it does the distribution of those credits by tax officials and the formation of a new consciousness viewing both taxes and social security contributions as the same sort of public obligation, may end up bringing about a reorganization in the nation's central bureaucracy in Tokyo's Kasumigaseki district, including such steps as the unification of the collecting authorities. There will be serious resistance to the introduction of such a system for this very reason. In short, bringing refundable tax credits to Japan is deeply tied to doing away with sectionalism in Kasumigaseki. Korea's Ministry of Strategy and Finance, which launched that nation's new system in January 2008, successfully overcame resistance from the offices in charge of social security, and the Office of the President showed leadership in designing and implementing the new program.

On December 24, 2008, the cabinet of Prime Minister Taro Aso approved a medium-term reform program for Japan's tax and fiscal system. This program will involve a reappraisal of various tax deductions and the tax rate structure with a view to restoring the individual income taxation system's original function of smoothing out disparities and redistributing income. It involves moves to increase the burden borne by high-income taxpayers, such as by adjusting the maximum tax rate and the upper limit to allowable deductions. At the same time, it will take a comprehensive approach to taxation and spending, including refundable tax credits and other aspects of the expenditures side, looking at ways to reduce the burden on middle- and lower-income households with attention paid to areas like child-rearing. The first step should be to secure needed revenues by paring back income deductions while converting them into tax credits, thereby increasing the system's income redistribution capacity. In the meantime we will also need to begin putting together concrete plans for a system tying together tax credits and refunds whose benefits will extend even to those whose income is below the minimum taxable level.

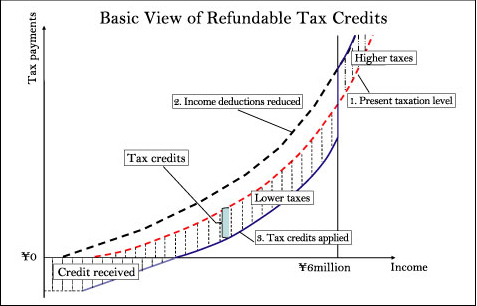

The attached chart in the above illustrates the idea nicely. In designing this system, the basic idea is to ensure that the overall system remains revenue-neutral. The present taxation scheme is represented by line 1; when income exemptions are reduced the effective taxation climbs to the level in line 2. This additional revenue is then used to provide refundable tax credits, amounts of which are determined by the number of children, for example, to households with total income below ¥6 million. This lowers the effective taxation on their income to the level in line 3. The result is that households below the ¥6 million income threshold pay lower taxes, while those with higher income pay more, thereby enhancing the income redistribution effect of the system.

If Prime Minister Aso were to position his proposed ¥2 trillion in cash handouts as the first step toward the creation of a system like this, they would be seen as more than mere political largesse. The decision of which form the system should take of the four categories described above-one aiming to reverse the falling birthrate, one to aid the working poor, one to make up for missed pension contributions from low-income individuals, or one to counter the regressive nature of consumption tax hikes-should be made on the basis of discussion among the people of Japan from now on.

Whatever the end result, what Japan needs today is strong political leadership that can overcome the divisions between the bureaucratic organs in Kasumigaseki. In this sense, the achievement of a new structure for Japan's income taxation will represent a touchstone for Japan as a state whose political leaders are firmly in charge.