- Article

- Japanese Politics

Japan’s Security Legislation from an Operational Perspective

November 5, 2015

There was very little debate on the actual substance of Japan’s recently enacted security legislation, despite the uproar it caused at home and abroad. Senior Fellow Noboru Yamaguchi provides an analysis of the provisions from a perspective closer to on-the-ground operations with reference to the new Guidelines for Japan-US Defense Cooperation, which sets the parameters for cooperation between the US military and the SDF.

* * *

In spite of the great commotion caused by Japan’s new security legislation, the content of the bills remained largely opaque to most people. The provisions are quite technical, and the government did not do a very good job of communicating their significance. Diet debate—which many complained was inadequate—focused narrowly on the wording of the provisions for specific contingencies and on their constitutionality. Critics have sought to build up opposition by labeling the bills “war legislation” and appealing to the public’s pacifist tendencies, but such name-calling served only to thwart serious debate on what the bills actually would enable Japan to do.

The tendency of the government to resort to legalese is quite understandable, given its need to explain the technical details of the proposed amendments and new stipulations. But it might be profitable to look at things from a perspective closer to on-the-ground operations. The new Guidelines for Japan-US Defense Cooperation, released in April 2015, represent the results of high-level deliberations with officials responsible for US military strategy and have been compiled from an operational perspective. Reference to this document, which sets the parameters for cooperation between the US military and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, would be extremely useful in terms of abetting an understanding of why the provisions were worded the way they were.

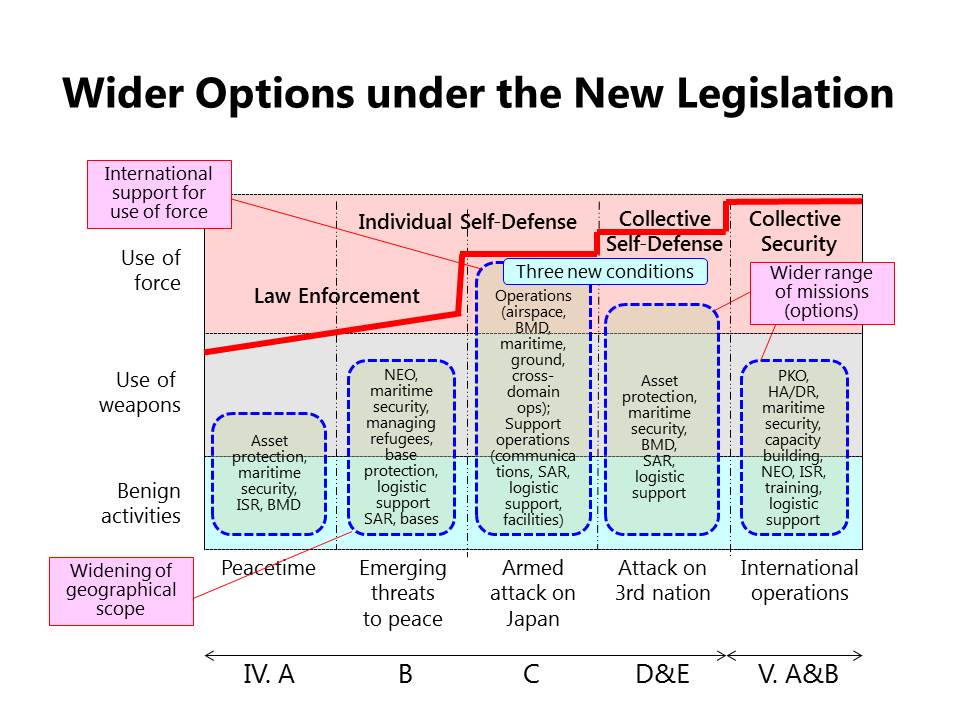

The new guidelines are organized into eight sections, of which Parts IV and V lay out concrete measures that might be carried out during operations involving SDF and US troops. These are Section IV, “Seamlessly Ensuring Japan’s Peace and Security,” and Section V “Cooperation for Regional and Global Peace and Security.” The relevant parts of these sections are as follows:

IV-A. Cooperative Measures from Peacetime

IV-B. Responses to Emerging Threats to Japan’s Peace and Security

IV-C. Actions in Response to an Armed Attack against Japan

IV-D. Actions in Response to an Armed Attack against a Country Other than Japan

IV-E. Cooperation in Response to a Large-Scale Disaster in Japan

V-A. Cooperation in International Activities (UN Peacekeeping Operations etc.)

V-B. Trilateral and Multilateral Cooperation

Sections IV-A through IV-E deal with responses to threats to Japan’s security. For example, IV-B widens the geographical scope of emergencies described as “situations in surrounding areas” in earlier versions of the guidelines, while IV-D defines the limited situations in which the right of collective defense might apply. By contrast, Sections V-A and V-B focus on how Japan and the United States will work together for the peace and security of the international community.

With the exception of Section IV-E, which outlines responses to large-scale disasters, the sections appear to be differentiated in terms of the levels of the potential use of weapons and military force. The figure below categorizes the actions treated in Sections IV-A though IV-D and Section V into differently colored zones according to the level of force they may involve: the blue zone involving no use of force, the yellow zone involving the use of weapons mostly for law enforcement, and the red zone involving military force. Some of the peacetime scenarios dealt with in Section IV-A may also involve the use of weapons in some scenarios, including responding to ballistic missile attacks and protecting assets.

The situation calling for the highest level of force involves a response to an armed attack on Japan. Article 88 of the Self-Defenses Law allows the SDF to use force “to the limit necessary for protecting the country” when a defense operations order is issued and conditions for the exercise of the right of self-defense are met. This kind of scenario, which under international law is regarded as an exercise of the right of individual self-defense, is the only case in which Japan can use military force.

The part of the guidelines that deals with the right of collective self-defense—which has been the focus of debate on the latest revisions to the national security law—comes in Section IV-D, “Actions in Response to an Armed Attack against a Country Other than Japan.” As the government has repeatedly explained, this right is limited only to such situations as when an attack “threatens Japan’s survival.” In other words, the situations in which this right would apply are very similar to the cases where the use of force for individual self-defense is permitted, such as a direct armed attack on Japan. The new legislation merely extends this right to situations that are more difficult to describe as relevant to the right of individual self-defense under international law.

In assessing the legitimacy of any use of force, I believe that the extent of international consensus required provides a useful measure. The bold red line in the figure shows what level of international support is necessary for the use of force in various situations. Under the UN Charter, the use of force requiring the highest level of international support involves cases of collective security, such as when a UN force is created by the international community to drive out an aggressor. Article 51 of the UN Charter acknowledges the right of individual or collective defense “until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security” as a second-best measure in cases where a UN response is not quick enough to defuse the situation. The recent legislation in Japan makes no supposition of any use of armed force in a case involving Japanese participation in a UN force, and the scenarios envisaged go no further than the yellow areas in the figure (use of weapons, limited use of force).

In cases involving the deployment of a UN force, the agreement of the entire international community, including all the permanent members of the Security Council, is required, which gives such actions a high level of legitimacy. In the case of collective self-defense, there needs to be a request from the party to be assisted, meaning that this will be based on an agreement between at least two countries—the one providing assistance and the one requesting it. No such conditions exist in the case of the right of individual self-defense, in which military force is exercised based solely on the decision of the country that has come under military attack (or deems such an attack to be imminent). We can therefore organize the three cases as follows: collective security requires the broadest consensus, individual self-defense requires the least, and collective self-defense somewhere in between.

The new security legislation does not go so far as to enable the SDF to engage in collective security arrangements as members of a UN force, but it does increase the options available short of such participation. For example, authorizing the SDF to use weapons to protect another country’s units or to carry out their missions during UN peacekeeping operations would open up the possibility of taking part in a broader range of missions, including those in which such a need could arise. As the figure shows, what is really new in the latest legislation is that it allows the limited exercise of the right of collective self-defense and that it geographically expands the areas where the SDF may be deployed to “situations that will have an important influence on Japan’s peace and security,” rather than just “situations in areas surrounding Japan.”

There are other changes providing for a greater range of concrete options that Japan may take that are within the parameters of the earlier constitutional interpretation and legal restrictions. For example IV-A, “Cooperative Measures from Peacetime,” specifies that the US and Japan “will provide mutual protection of each other’s assets if engaged in activities that contribute to the defense of Japan in a cooperative manner.” This is asset protection. This gives the SDF the right to use weapons to protect firearms and other military equipment through an extension of the thinking that has been in place for some time.

To make the debate over the security legislation more fruitful, it is important to look at concrete examples of possible scenarios. It is also necessary to understand the position that such examples occupy within the overall framework of Japan’s national security policy.

In that sense, the new guidelines provide a comprehensive vision that covers everything from peacetime to national emergencies and international cooperation, making it a relatively easy way to understand where each of the individual arguments stands in terms of the overall picture.