Prickly relations between Tokyo and Beijing are nothing new, but the current squabble over the Senkaku Islands makes the previous two decades look like a honeymoon. Katsuyuki Yakushiji discusses the underlying structural changes that have turned the tiny Senkakus into a powder keg.

* * *

Relations between Japan and China have hit a new low. The countries’ top leaders do not even exchange smiles or handshakes at international conferences, let alone lay plans for state visits. Diplomats are denied contact with major government figures in the host country except at ceremonial occasions. Senior Japanese officials euphemistically call it a “strategy of endurance.”

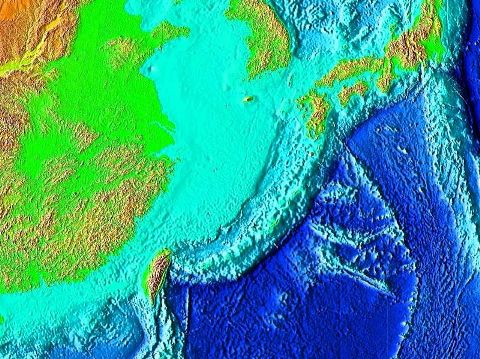

Although the immediate cause of this diplomatic dysfunction is the dispute over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, the underlying source of tension is much deeper and more difficult to address.

Nostalgic for the Nineties

Of course, this is not the first spat between Tokyo and Beijing in recent history. In the 1990s, President Jiang Zemin—whose uncle died fighting the Japanese during World War II—missed no opportunity to bring up Japan’s wartime aggression. He routinely complained that the Japanese government had never offered a proper apology, and Tokyo countered each time that it had already done so. Despite these simmering tensions, though, diplomatic relations continued to move forward.

Indeed, the two governments were able to build on progress made at the bilateral level to embark on such multilateral frameworks as the Japan–China–South Korea trilateral summit, first held in 1999 at the initiative of Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi. This meeting, held almost annually for the next decade, provided an opportunity to deliberate North Korea’s nuclear program and other key issues affecting the Northeast Asian region as a whole.

Progress slowed dramatically during the administration of Prime Minister Jun’ichiro Koizumi. The issue then was the prime minister’s annual visit to Yasukuni Shrine beginning in 2001, the year he took office. The Chinese government strongly protested the visits on the grounds that, by paying his respects at a shrine that enshrines class A war criminals, the prime minister was, in effect, condoning the militaristic and expansionist policies of the past. During Koizumi’s five years in office, state visits between the two countries came to a halt. Even so, both governments managed to take advantage of APEC meetings and other multilateral frameworks to maintain some form of bilateral dialogue at the top, and trilateral talks between Japan, China, and South Korea were never completely suspended.

One of the first things Prime Minister Shinzo Abe did upon succeeding Koizumi in 2006 was to visit China. Abe and President Hu Jintao issued a joint statement calling for efforts to build a “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests,” and relations improved almost overnight. Abe left office after barely a year, as did the next two prime ministers, Yasuo Fukuda and Taro Aso. But despite the rapid turnover in Japan’s top leadership, the two countries continued to make diplomatic progress, including an agreement for joint development of gas reserves in the East China Sea. Two major factors account for this upturn. First, Japan’s top leaders refrained from visiting Yasukuni Shrine. Second, the hardline Jiang Zemin was replaced by Hu Jintao, a proponent of stronger relations with Japan.

Stormy Waters

Sometime after the Democratic Party of Japan unseated the Liberal Democratic Party in 2009, things took a decided turn for the worse. Tensions began to rise sharply in September 2010, after a Chinese trawler deliberately rammed a Japanese Coast Guard patrol vessel in the East China Sea near the disputed Senkaku Islands. Japanese authorities arrested and detained the ship’s captain on charges of obstructing officers on duty, and Beijing reacted furiously, denouncing the arrest and suspending all high-level exchanges with Japan.

When Japan continued to hold the ship’s captain, China retaliated by blocking exports of rare earth metals to Japan and detaining four Japanese corporate employees who were visiting China on business. Eventually Japanese officials decided to release the captain without indictment and send him home, but by then Beijing’s rabid response—mobilizing the state apparatus at all levels and applying pressure in sectors unrelated to the issue at hand—had already caused consternation around the world.

Then, after a brief lull, came the series of events that have brought relations to their current deplorable state. In September 2012, the cabinet of Yoshihiko Noda decided to purchase three of the Senkaku Islands. The government moved to nationalize them after learning that Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara, an outspoken hawk on China policy, was planning to purchase the disputed islands, incorporate them into Tokyo Metropolis, and build wharves and lighthouses on them, regardless of the consequences for Japan-China relations. Noda met personally with the governor to confirm whether these were indeed Ishihara’s intentions, after which the central government went ahead with the decision to nationalize the islands in order to avert a worst-case scenario.

Noda explained that the purpose of the purchase was to ensure the “peaceful and stable management of the islands” over the long term. But Beijing erupted in indignation, calling such a unilateral move “illegal and invalid.” Since then, China Coast Guard vessels have been dispatched to the islands on an almost daily basis, often making incursions into Japan’s territorial waters. Japan, meanwhile, has a fleet of Coast Guard vessels on hand to patrol the waters on an ongoing basis. As Japanese and Chinese coast guard ships face off, both countries’ naval vessels are keeping close watch from outside the disputed area.

Chinese aircraft have been encroaching on Japanese airspace more frequently, causing Japan to scramble its jet fighters in response. In short, Japan and China are locked in a tense standoff over a group of tiny, uninhabited islands in the East China Sea.

In late November 2013, moreover, China unilaterally announced an air defense identification zone over broad areas of the East China Sea, including the Senkaku Islands. Needless to say, this ADIZ overlaps that already established by Japan, and it also intrudes into a South Korean–claimed ADIZ. China maintains that any planes flying into this airspace must comply with Chinese orders and inform authorities of its flight plan, warning that any aircraft failing to follow such rules will face emergency defense measures taken by the military. Tokyo, Washington, and Seoul have all voiced serious concern over Beijing’s action as unnecessarily heightening tensions in the region.

While the squabble has all the appearance of a typical territorial dispute, China’s first attempt to claim the Senkaku Islands dates back only to the early 1970s—when a UN survey revealed the strong likelihood of oil reserves in the vicinity. Before then, China never disputed Japan’s sovereignty over the islands. The Senkakus have remained under Japan’s control during this time, and the Japanese government maintains that there is no territorial dispute.

Why, then, have the islands suddenly turned into such a bone of contention? Even allowing for the volatility of Beijing’s relationship with Tokyo over the past two decades, it seems clear from the intensity of the current conflict that the dynamic of the Japan-China relationship has fundamentally changed.

Historical Issues and the Murayama Statement

Until the 1990s, the periodic escalation of tensions between Japan and China almost invariably revolved around historical issues. Every so often, politicians from the LDP’s hawkish, nationalistic wing, including top party officers and cabinet ministers, would come out with remarks that sought to justify Japanese aggression against China in the 1930s, claiming, for instance, that Japan was forced to invade China in self-defense or that Japanese expansion in East Asia and the Pacific liberated the region’s nations from Western imperialism. Each of these outbursts was followed by an indignant backlash from China and a temporary deterioration in bilateral ties.

However, the Japanese government has long since made its position clear. On August 15, 1995, Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama issued a statement, with the unanimous approval of the cabinet, that leaves no doubt as to Tokyo’s official stance on the issue of Japan’s imperialist and wartime aggression. The statement “On the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the War’s End,” also known as the Murayama statement, reads in part as follows:

“During a certain period in the not too distant past, Japan, following a mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war, only to ensnare the Japanese people in a fateful crisis, and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations. In the hope that no such mistake be made in the future, I regard, in a spirit of humility, these irrefutable facts of history, and express here once again my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology. Allow me also to express my feelings of profound mourning for all victims, both at home and abroad, of that history.”

In this statement, the Japanese government explicitly acknowledges and apologizes for the aggression of the past. Moreover, subsequent cabinets have continued to honor this statement, reaffirming its substance and often quoting it verbatim.

Changing Dynamic

However, much has changed since 1995. At the time of the Murayama statement, Japan was still the world’s second largest economic power, and its security environment was relatively stable thanks in large part to the Japan-US alliance. Confident in its superiority, Japan could afford to be tolerant and magnanimous, and the public was largely immune to the appeal of narrow-minded nationalism.

After the start of the new millennium, however, the bilateral power balance gradually shifted. Japan’s economy remained mired in the protracted slump ushered in by the collapse of the economic bubble, while China’s economy grew by leaps and bounds as the “Reform and Opening up” policies bore fruit. In 2010, China finally overtook Japan in gross domestic product to become the world’s second-largest economy.

A similar shift has occurred on the security front. Owing largely to fiscal constraints, the Japanese defense budget has remained virtually unchanged since the 1990s at about 5 trillion yen. Meanwhile, China’s defense budget has quadrupled over the past decade to 16 trillion yen (2012), as Beijing has pursued a policy of rapid military expansion and modernization.

The heady mix of high-paced economic growth and military modernization has boosted China’s self-image as a major power. Its behavior toward its neighbors—not only around the Senkaku Islands but also in disputed areas of the South China Sea—has become high-handed, producing growing friction. In Japan, resentment of China’s imperious approach to international relations is compounded by its having been overtaken as the preeminent regional power. The result has been a marked rise in anti-Chinese nationalist sentiment. A hawkish, hard-line stance toward China has become more prominent, while calls for bilateral friendship and cooperation have become subdued.

This trend was vividly apparent in the results of a public opinion survey on foreign relations conducted in October 2012 by the Cabinet Office. In that year’s survey, only 18.0% of respondents indicated that they felt friendly toward China, while 80.6% answered that they did not. Asked about their perceptions of the Japan-China relationship, a mere 4.8% characterized it as good, while 92.8% said that it was not good. It cannot be entirely coincidental that Shinzo Abe, a noted hawk, was elected president of the LDP in September that same year and went on to become prime minister following the LDP’s landslide in the December 2012 election.

The agenda that Abe has sought to advance since taking office a second time would probably, in previous years, have been have rejected by more moderate forces in his own party. Abe has outlined the need to amend the Constitution, or at least to change the government’s constitutional interpretation to permit participation in collective self-defense. A new National Defense Program Guidelines are being drafted with a view to beefing up Japan’s defenses around the Senkakus and other remote islands. And he is laying the groundwork to establish a Japanese version of the National Security Council. At some level, each of these initiatives is aimed at China. And today, owing to the strained bilateral relations and widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in Japan, Abe has the entire LDP behind him.

The US Factor

But China and Japan are not the only parties involved here. The United States is also a crucial part of the picture. Japan cannot hope to face down China except as a partner in the Japan-US alliance. Yet Washington is working actively to build a stable relationship with Beijing.

The three-way Japan-China-US relationship cannot be reduced simply to the Japan-US alliance versus China. The United States does not want to turn China into an enemy; it wants to incorporate the country into a US-led international order. This is the strategy underlying Washington’s haste to conclude negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership and its strong insistence on freedom of navigation and respect for international law in the South China Sea. It goes without saying that Japan is a key component of that strategy.

China, however, is not content to become part of a US-led international order. Instead, it is doing its utmost to expand its own sphere of influence. As a consequence, competition is heating up as China challenges the US hegemony in the region. The rising tension between China and Japan must be understood in this context.

As the foregoing suggests, the reason relations between Japan and China have become so dysfunctional and difficult to repair is that the source of tension is much larger and deeper than the immediate cause. This also means is that, until the establishment of a new regional order that acknowledges China as a major power—a process that is sure to take some time—any improvement in Japan-China ties is bound to be fleeting.