Overcoming Constraints and Addressing Longer-Term Challenges

1. New Constraint on Japan's Basic Energy Policy

The 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station has deeply shaken the Japanese people's faith in nuclear energy. As a consequence, the government has been forced to rethink the nation's Basic Energy Plan, under which nuclear power was assigned a pivotal role in the nation's energy strategy.

As of this writing in May 2012, all 54 of Japan's nuclear reactors are shut down, most in the name of "routine maintenance," and it is difficult to say whether circumstances will permit any of them to resume operations.

The deep distrust that the Fukushima accident instilled in the Japanese people is not the only obstacle to the resumption of nuclear power generation in Japan. The industry also faces skyrocketing construction costs from new requirements to make plants capable of withstanding major natural disasters, as well as unresolved technical problems pertaining to the back end of the nuclear cycle (such as the disposal of radioactive waste). In the absence of concrete solutions to these challenges, the development of a new national energy policy is constrained by the unfeasibility of an energy strategy that relies heavily on nuclear power .

2. Outlines of a Basic Energy Policy Premised on This Constraint

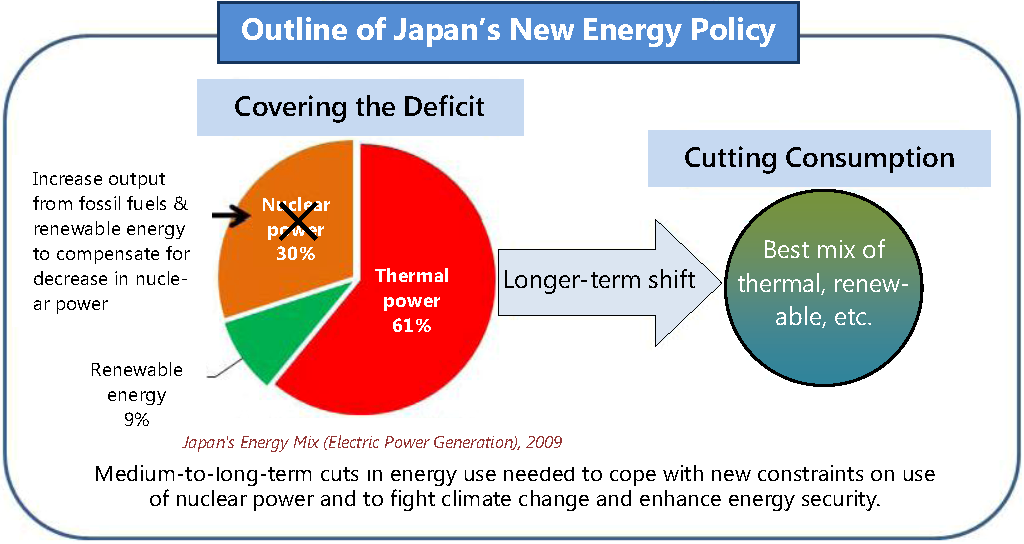

If we operate on the premise that Japan can no longer depend heavily on nuclear energy, which previously supplied one-third of the nation's electricity, we are left with two possible strategies—very broadly speaking—for meeting our future energy needs.

The first is to "cover the energy deficit," compensating for the shutdown of nuclear plants by generating more power from conventional thermal power generation (using fossil fuels) on the one hand and alternative or renewable energy sources on the other.

The second approach is to "cut energy consumption. " This focuses on reducing energy demand from current levels over the medium to long term by promoting new energy-efficient technologies and lifestyle changes, assisted by a dwindling population.

The former, which seeks only to make up for lost nuclear power, might be characterized as being realistic but devoid of vision. The latter, with its exclusive focus on reducing demand through technological innovation and lifestyle changes, meanwhile, can be described as full of ideals but divorced from reality.

At the same time, the reduction of energy consumption farther down the road is an important goal not only from the perspective of building an energy policy less dependent on nuclear energy but also from the standpoint of stemming climate change and enhancing energy security .

In recent years the Japanese government has drawn up various and sundry policy documents outlining bold new energy goals for the nation, with titles like New National Energy Strategy, 21st Century Environmental Nation Strategy, and Biomass Nippon Strategy. Yet so far, none of these goals has come to fruition.

What are the reasons for this failure? One, no doubt, is that the goals set forth were too far removed from reality (that is, the gap between ideals and reality was too wide). Another is that the policy goals were not backed by a practical plan of action consisting of concrete and specific policy measures (that is, policies never evolved past the stage of wishful or abstract thinking).

In formulating a new energy strategy, therefore, Japan must not simply choose between a "cover the deficit" and a "cut consumption" approach. Rather, our energy policy should be a seamless blend of realism and idealism , focusing on the deficit-covering strategy to cope with pressing realities while adopting policy measures designed to move us toward the ideal of reduced energy consumption over the medium to long term.

This will require the government to determine what energy resources the nation needs, identify in specific and concrete terms the potential obstacles to securing and utilizing those resources, decide which issues are the most urgent in the light of international developments and time considerations, and address those issues on a priority basis.

3. Twin Imperatives: Securing Fossil Fuels and Expanding Renewable Energy

Whether the focus is on covering the energy deficit or cutting energy consumption, for the foreseeable future there will be a continued need to (1) secure supplies of fossil fuels, and (2) expand the use of renewable energy. Indeed, even if nuclear power generation is resumed and reemerges as a viable energy option, these would still be vital tasks from such standpoint s as climate-change mitigation, energy security, and the development of green industries, as indicated by their prominent place in the government's Basic Energy Plan to date.

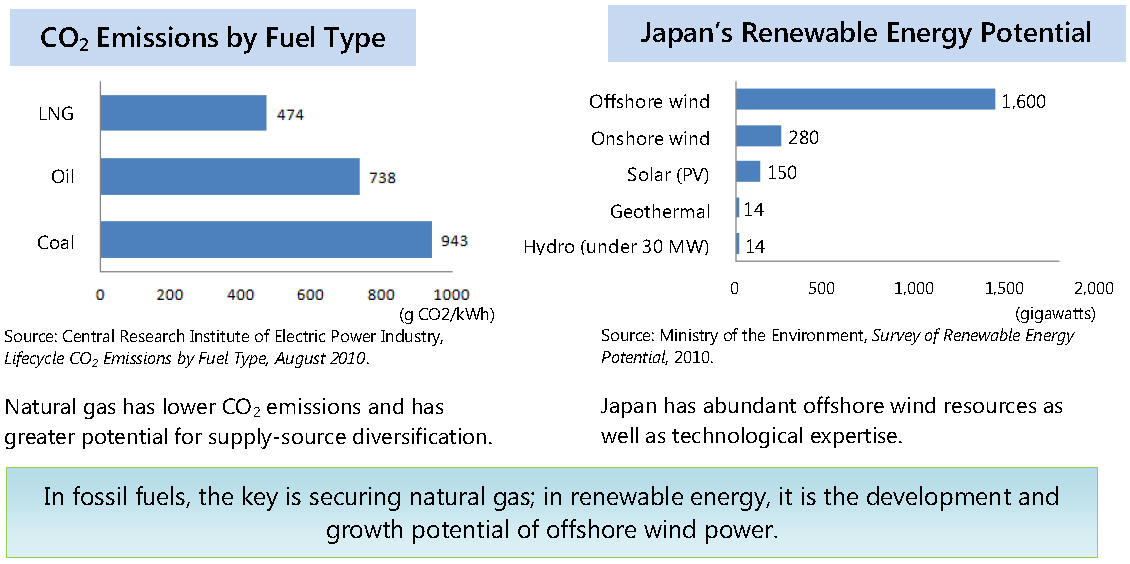

In short, securing supplies of fossil fuels and expanding the use of renewable energy are both imperatives for any basic energy policy going forward. And among the various options available in these two categories, the best ones are natural gas and offshore wind power, respectively.

The main fossil fuel options are oil, coal, and natural gas. With oil comes worries over rising prices and unreliable supply, given recent political instability in the Middle East. Coal offers better supply stability, but higher carbon emissions make it a poor choice from the standpoint of stemming climate change.

Natural gas, on the other hand, offers potential for greater diversification of supply sources than oil, and it is the cleanest of the fossil fuels in terms of carbon emissions. In addition, Japan has made great technological progress in the efficient combustion of natural gas. For these reasons, natural gas should be considered the strongest candidate for the position of Japan's key fossil fuel in the years ahead.

At the same time, Japan is blessed with great renewable-energy potential thanks to a richly varied natural environment that includes an extensive coastline and numerous volcanoes and hot springs.

Among the renewable-energy options available to Japan are geothermal, solar (photovoltaic), solar thermal, onshore and offshore wind, micro hydro, and biomass. Of these options, offshore wind power offers by far the greatest potential for our future energy supply. Japan has plentiful offshore wind resources, and with offshore wind power, development is not limited by the availability of land. In addition, Japan excels at the technologies needed for the development of offshore wind power.

Accordingly, if Japan aims to expand its supply of renewable energy, offshore wind power is the most obvious candidate to play a leading role, and much will depend on extent to which we can make use of this resource.

In revamping Japan's energy policy, therefore, the government should place high priority on securing supplies of natural gas and exploring the practical potential for offshore wind power development, and work quickly to identify and address the challenges ahead.

4. Proposals regarding Natural Gas

(1) Divers ify sources and forms of access to ensure stable supply and hold down costs

Leading candidate to replace nuclear energy

With Japan's nuclear reactors offline indefinitely as a consequence of the nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan has no choice in the short term but to compensate for the loss of electric power from nuclear energy by increasing the output of electricity from fossil-fuel-burning plants. Because of its cost and environmental advantages, liquefied natural gas is the fossil fuel of choice to offset the loss of nuclear power. The Institute of Energy Economics estimates that Japanese demand for LNG in fiscal 2012 will jump about 20 million tons from 2010 if the nation's nuclear power plants remain offline.

Instability in the Middle East and rising procurement costs

According to estimates issued by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, the shutdown of Japan's nuclear power facilities is likely to add 3.1 trillion yen in fuel costs to the nation's energy bill in fiscal 2012. Meanwhile, the unstable situation in the Middle East, including the situation in Iran, raises the real possibility of an interruption in LNG exports from Qatar, currently the world's largest producer. It is essential that Japan develop a plan to secure reliable access to natural gas while keeping down procurement costs.

Japan pays too much

Broadly speaking, there are three major world markets for natural gas: North America, Europe, and the Pacific Basin. In the North American market, spot prices have fallen sharply since 2009, thanks to the exploitation of unconventional natural gas resources, including shale gas (the so-called shale-gas revolution). As of this writing, Henry Hub prices are averaging around $2/MMBtu (million British thermal units). Japan, on the other hand, depends on imports of liquefied natural gas, and the pricing of LNG in the Pacific Basin is based on long-term contracts and linked to the movement of oil prices. As a result, Japan pays about $16/MMBtu, roughly eight times North American prices.

To be sure, it is virtually meaningless to compare the Pacific Basin market with North America, since the latter produces so much of its natural gas internally and is equipped with an extensive pipeline network to transport it, allowing it to be bought and sold at spot prices. However, it is worth noting that the price system in Europe was also based on long-term contracts—generally for gas procured via pipeline—and tied to oil prices, but the ripple effect of the shale gas revolution has begun to erode the old price structure, as LNG from Qatar that would have gone to North American has instead rushed into Europe at spot prices below contract prices for pipeline gas. As a result, the average purchase price of natural gas in Europe is also markedly cheaper than in Japan, at about $10/MMBtu. What this tells us is that Japan, too, needs to diversify its supply sources and forms of access to natural gas, both to ensure a stable supply and to keep down costs.

North America and Russia hold the key

The key to diversifying Japan’s supply sources and forms of access lies with producers: North America—where the "shale gas revolution" has opened the way to production of cheap natural gas—and Russia, which holds rich gas reserves on Sakhalin Island, just north of Japan, and may eventually be able to supply that gas in a form other than LNG, namely, via pipeline.

(2) Design a procurement strategy combining North American shale gas and Russia's Sakhalin reserves

The potential of North American shale gas

Importation of North American shale gas could mean significant savings for Japan. Even adding in about $10/MMBtu in extra costs for liquefaction and shipping, the estimated price is $12/MMBtu, as against the current level of $16. The main obstacles are the absence of a Japan-US free trade agreement, which is needed for US companies to export LNG to Japan, and American concerns that LNG exports could push up domestic gas prices. At this time it is impossible to predict how much of its own natural gas the United States may ultimately be willing to export.

The increase in US production means, though, that Canadian natural gas (including shale gas) that was previously exported to the United States can be channeled to Asian markets instead.

In view of the current situation, Japan should look to Canada for the bulk of its North American shale gas, while at the same time laying the groundwork for procurement from the United States with an eye to strengthening the Japan-US security alliance.

Expanded imports from Sakhalin

Japan is currently meeting 9% of its total gas demand from the Sakhalin-2 Project, and it can also look forward to gas from Sakhalin-1, which has yet to be earmarked for export, as well as from Sakhalin-3 once production gets underway. In all, Sakhalin holds great promise as a long-term, stable source of natural gas for Japan.

A Japanese consortium including Itochu and Marubeni is currently working with the state-controlled Russian natural gas giant Gazprom on a feasibility study for construction of a major plant in Vladivostok to liquefy natural gas, including that produced by Sakhalin-1, for shipping to Japan and other destinations.

All of this points to the need to formulate a gas procurement strategy centered on both North America, where the "shale gas revolution" has facilitated the production of cheap natural gas, and Russia, which holds rich gas reserves centered on Sakhalin, just north of Japan.

(3) Revisit the Sakhalin-Japan pipeline plan

Improving access to Sakhalin gas

In the early 2000s, US oil giant Exxon Mobil, leader of the Sakhalin-1 Project, was pushing plans to build a gas pipeline from its Sakhalin gas fields to Japan. The project ran aground, however, supposedly owing to political obstacles on the Japanese side.

Exxon Mobil does not seem to have given up hope of building a pipeline from Sakhalin, but Itochu, Marubeni, and other members of the Japanese consortium involved in Sakhalin-1 are pursuing other angles, as suggested by the aforementioned feasibility study for an LNG plan in Vladivostok.

According to estimates made in the early 2000s, however, a pipeline from Sakhalin had the potential to lower Japan's gas procurement costs significantly, reducing electricity rates in the process. Under the circumstances, it would make sense for the government to take the initiative in reexamining the feasibility and economic benefits of Exxon's pipeline plan, taking care to reach an understanding with the Japanese fishing industry before proceeding.

5. Recommendations for Development of Offshore Wind Power

(1) Speed up trials of floating wind turbines

Offshore wind power can be generated either by fixed-bottom wind turbines or floating turbines. In Europe, where offshore wind power has made great inroads, fixed-bottom turbines are the rule, primarily because the coastal waters are relatively shallow. In Japan, with its deeper coastal waters, construction of bottom-mounted towers raises serious challenges. For this reason, floating wind farms may be the most promising option for Japanese wind power in the years ahead.

With its advanced shipbuilding technology, Japan has the basic technical know-how needed to develop floating offshore wind power facilities. In addition, Japanese companies hold a major share of the global market for various wind turbine components.

Globally, the development of floating wind technology is still in its infancy. The most promising project to date is an installation by Norway's Statoil and Germany's Siemens Wind Power about 12 kilometers off the coast of Karmøy, Norway, which has been undergoing trials since 2009. As yet, there are no facilities operating commercially.

In Japan, meanwhile, the Ministry of the Environment has plans to install a 2 megawatt demonstration floating turbine off of Kabashima (Goto Islands, Nagasaki Prefecture) in 2013. METI, too, is advancing a wind farm demonstration project to install six 2 megawatt turbines off the coast of Fukushima, scheduled to operate through 2015. At this stage, however, Japan still lacks a working model of floating wind power, let alone the empirical data to accurately assess the true costs and determine what it will take for the technology to catch on.

It seems clear that the development of floating wind technology is crucial if Japan is to take full advantage of wind power's unparalleled potential as a renewable energy source. Yet the report on energy costs issued by a subcommittee of the government's Energy and Environment Council in December 2011 had nothing at all to say about floating wind technology, although it provided cost estimates for onshore wind, fixed-bottom offshore wind, geothermal, solar, micro hydro, and biomass energy.

The government must move quickly to complete operational trials of floating wind turbines so as to determine the extent of the role offshore wind power can play in Japan's energy mix and develop effective policy measures to support wind power development.

The government should also consider the role floating wind technology could play in the development of Japan's green industries. With floating wind technology still in the developmental stages globally, Japan has a strong chance of emerging as a world leader in commercial application of floating wind turbines, providing it moves quickly to complete operational trials.

(2) Conduct trials with an eye to international standards development

Keeping an eye on the development of standards

Although floating offshore wind farms are still at the developmental phase worldwide, discussions are already underway for the drafting of international technical standards.

Not long ago, South Korea took the lead in this process by submitting a proposal to the International Electrotechnical Commission to create a working group on international standards for floating offshore wind turbines. In May 2011 the IEC accepted the proposal and set up such a group within the technical committee on wind turbines (TC 88). Not surprisingly, South Korea, as the originator of the proposal, secured chairmanship of the group, putting itself in a position to lead deliberations on the development of international standards for floating wind turbines.

Under the World Trade Organization's Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, members are required to abide by international standards developed by such public international bodies as the International Standards Organization and the IEC. For this reason, the development of international standards is always a focus of intense diplomatic jockeying as countries attempt to position their own technology as the international standard that will eventually dominate global markets.

Japan needs to keep a watchful eye on this process. Offshore wind power, which has vast potential for Japan, is an area that lends itself well to the application of Japanese technology. It would be a shame to find ourselves unable to utilize and disseminate our own technology because we fell behind in the race for international standardization.

Standardization schedule

Under the original schedule, the floating offshore wind turbine working group was to adopt a working draft sometime in 2012 with a view to establishing the standards sometime in 2013. However, the draft submitted by the South Koreans at the working group's first meeting in September 2011 was criticized as inadequate and failed to win approval. The working group decided to go back to square one and begin formal deliberations only after it had a working draft that incorporated the accepted criteria for international standards.

Taking the lead through prompt c omplet ion of trials

Had the draft specifications submitted by South Korea been approved, the development of international standards for floating offshore wind turbines would have proceeded according to the South Korean design. But because of the working group's decision to start over, Japan has a second chance to provide technical input and shape the process.

That said, the window of opportunity for Japan is narrow. Countries possessing empirical data naturally have a greater voice in the standards development process. For this reason, Japan needs to conduct and complete operational trials without delay, with the following in mind.

- The schedule for operational trials should be linked to the standards development timetable.

- A country to watch is Norway (both its technologies and involvement in standards development), given its head start in operational trials.

(3) Encourage the fishing industry's involvement in offshore wind power

The importance of community cooperation

The Japanese government is conducting a variety of projects oriented to the expansion of renewable energy, from studies to gauge the potential of various resources to development of new and better technologies for their use. However, amid all these efforts, we must keep in mind another basic condition for the spread of renewable energy.

Renewable energy is local energy technology, depending as it does on the natural resources and conditions—wind, sunshine, geothermal energy, water—of a particular area. To effectively utilize those resources, it is essential above all else to secure the understanding and cooperation of the local residents.

If the government neglects this aspect of energy development and bases its predictions of penetration and optimum energy mix solely on the basis of resource potential and technological considerations, there is a very real danger that government policy will find itself at odds with reality, and the growth of renewable energy will founder in the face of community opposition.

In promoting the expansion of renewable energy, the government must formulate policy measures that are capable of winning the understanding of the local community.

Local cooperation for floating offshore wind power

Floating offshore wind technology is still in its infancy, and if Japan can lead the way in its development, it has an opportunity to promote its own technology throughout the world. But because floating offshore wind has no track record of practical use anywhere in the world, let alone inside Japan, people have no idea what it would entail and how they would be affected.

In Japan, the Ministry of the Environment has plans to install a 2 MW demonstration floating turbine off Kabashima in 2013, and METI is implementing a multi-turbine floating wind farm project off the coast of Fukushima through 2015. In the meantime, however, the government needs to work quickly to provide the public with a concrete image of these facilities.

In addition, these pilot projects should be designed not merely to verify technical viability but also to demonstrate how floating wind power facilities can coexist with the community and provide a model for partnership between the electric power companies and local residents based on voluntary community participation.

Involving fishers in wind turbine operation

Once the floating wind turbines are installed, their presence will create a variety of opportunities for on-site work, including regular maintenance, environmental surveys, and patrols to enforce navigation safety zones. Since this will be offshore work necessitating the use of boats, it could offer important opportunities for participation by local fishing workers.

In advance of the Environment Ministry's demonstration project off Kabashima, discussions were held with the local fishing cooperative, which agreed to seek the cooperation of local fishers for environmental surveys, maintenance, and other work expected to arise in connection with the study.

Norway, which currently leads the world in piloting floating wind power, has developed special boats designed for both fishing and efficient operational support for floating wind turbines so as to allow fishers to take part in their operation.

These trends suggest the possibility that offshore wind power could become a new marine industry in which workers cultivate and harvest electric power in the same manner as they might cultivate and harvest oysters or scallops—without being subject to fluctuations in yield.

The government needs to foster a mutually beneficial partnership between the fishing and power industries by supporting the development of a business model that incorporates this concept.

Conclusion: Integrating Basic Policy with Practical Measures

The government is currently deliberating the outlines of a new energy policy, to be issued this summer in the form of an "Innovative Strategy for Energy and the Environment," a new Basic Energy Plan, and other policy documents. The central purpose of the effort is to redefine Japan's optimum energy mix in the wake of the accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. However, a statement of policy goals has little meaning unless it is accompanied by a roadmap composed of concrete measures for their achievement.

For example, the government can call for increased output from conventional thermal power plants to compensate for the loss of nuclear power, but without concrete measures for securing supplies of natural gas, the prospects for meeting demand are uncertain.

Similarly, the government can incorporate offshore wind power as a major component of Japan's optimum mix, noting its high potential as an alternative energy source for Japan, but until it has data from on-site trial operations using real equipment, it has no way of knowing the true costs and practical obstacles to widespread adoption.

In short, the drafting of basic energy policies, including the optimum energy mix, must be carried out in tandem with the formulation of the concrete measures needed to carry out those policies.

In this proposal, we have offered basic recommendations for policy measures pertaining to several key energy challenges facing Japan. We urge the government to incorporate these recommendations in its planning to ensure that the new policy scheduled to be unveiled this summer amounts to more than an exercise in abstract or wishful thinking.

Reform of Japan's energy production and distribution system is expected to emerge as a major focus of the energy debate. A basic energy policy firmly grounded in practical policy measures is a precondition for any meaningful discussion of this system, which must be designed to facilitate the energy mix envisioned. For this reason as well, the government is urged to draw up a national energy policy and strategy grounded in concrete policy measures as outlined in this proposal.