The international community remains deeply divided over one of the most urgent global challenges of the twenty-first century: how to guarantee efficient and equitable taxation in today’s rapidly growing digital economy. The Foundation’s Naoki Oka discusses the nature of the problem and Japan’s crucial role going forward.

* * *

Albert Einstein is said to have remarked, “The hardest thing in the world to understand is income taxes.” That was more than 70 years ago. Today, it has become an even greater challenge, as international tax experts and policymakers struggle to agree on fair and effective strategies for taxing business activity in a global economy increasingly dominated by a handful of immensely powerful tech firms.

Sizing up the Problem of Digital Tax Avoidance

According to figures published by the European Commission, average annual revenue growth for the world’s top digital firms is 14%, as compared with 0.2%–3% for other businesses. Yet according to the same source, the effective tax rates paid by those digital companies is a mere 9.5%—less than half the 23.2% paid by conventional firms on average.

Today, a handful of big tech firms are raking in enormous profits, having secured monopolistic control over their respective markets, along with vast amounts of data. They are among the world’s top-ranking firms in terms of market capitalization, yet they create relatively few jobs compared with such conventional businesses as supermarket chains or automakers. Facebook is worth far more than General Motors, for example, but its workforce is a fraction of the size of GM’s. In fact, Facebook’s market cap per employee is higher than GM’s by a factor of 70–90.

Tech giants do a thriving business around the globe and depend heavily on overseas sales. In 2016, about 65% of Apple’s revenue was generated outside the United States. In the same year, non-US revenues accounted for 54% of Facebook’s earnings, 53% of Google’s, and 32% of Amazon’s. Clearly, the challenge of taxing the digital economy is an issue of global import.

Tech Firms and Tax Havens

As noted above, the average effective tax rate for the top digital firms is substantially lower than for other companies—in some cases, surprisingly low. According to testimony submitted by Apple Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook to a 2013 US Senate hearing, Apple’s Irish subsidiaries paid an effective annual tax rate of less than 2% to the Irish government over a period of more than a decade. The reason is not that Apple evaded taxes in Ireland but that it took advantage of opportunities for tax avoidance afforded by Ireland as a noted tax haven.

The big US-based tech firms routinely shield their revenue from overseas taxes with the help of subsidiaries located in such havens—Ireland in the case of Apple, Google, and Facebook; Luxembourg in the case of Amazon. In some instances, moreover, these giant tech firms have used their economic clout to secure preferential tax treatment even within those tax havens, thus running afoul of the European Union’s competition statutes.

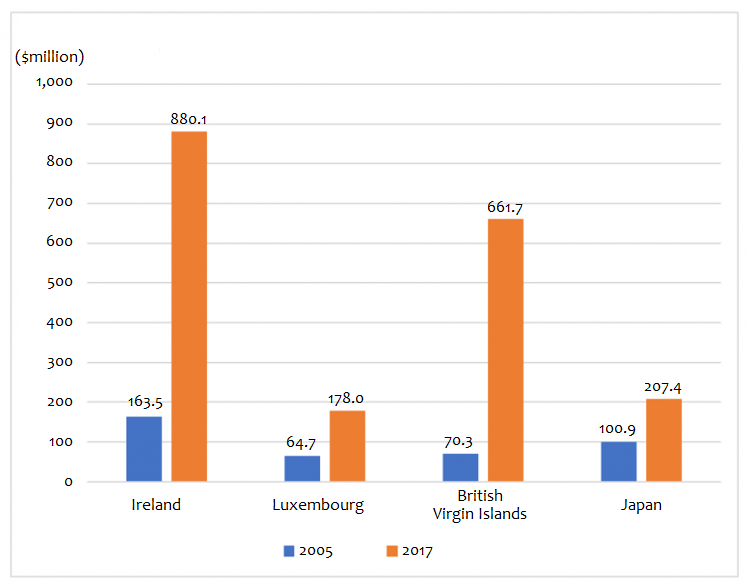

Tax havens like Ireland use low tax rates and tax breaks to attract foreign direct investment, and the FDI trends charted in figure 1 suggest that they have been successful in that strategy.

Figure 1. Growing FDI Inward Stock of Selected Countries, 2005 and 2017

Source: UNCTAD STAT

Ireland’s policies trade corporate tax revenues for employment, but the payoff in terms of jobs would appear to be limited. In 2011, according to figures released at the aforementioned US Senate hearing, Apple’s Ireland subsidiary Apple Sales International posted profits totaling US $22 billion (most of which went untaxed under Ireland’s preferential tax treatment). But as of 2012, all of the company’s local operations combined employed only 2,700 people.

Meanwhile, the European Commission ruled in 2016 that Ireland’s tax treatment of Apple constituted illegal state aid under the EU’s competition statutes, and it ordered Ireland to recover the unpaid taxes, with interest, for the years 2003 to 2014[nk2] . According to news reports, as of September 2018 Apple had paid the entire sum, something in excess of 14 billion euros (more than $15 billion)—a surprisingly big sum comparable to Japan’s annual inheritance tax receipts. In 2017, the EC ordered Amazon to reimburse Luxembourg for illegal tax benefits totaling 250 million euros, or almost $300 million.

Another indicator of the surge in international tax avoidance is the ballooning profits multinational corporations attribute to their subsidiaries in tax havens. In 2012, Irish subsidiaries of US-based firms reported profits totaling $135 billion, roughly 60% of Ireland’s gross domestic product. Luxembourg subsidiaries of firms like Amazon reported $68 billion in profits altogether, a sum surpassing the country’s GDP by about 20%.

How can it be, one might ask, that the GDP of Luxembourg is less than the combined revenue of the corporate subsidiaries registered there? The fact is that most of the revenue reported by subsidiaries in tax havens is generated outside the country and thus does not contribute to the GDP of the tax haven. One possibility is that profits are being shifted from the countries where they are generated to low-tax (or no-tax) jurisdictions.

Figure 2. Increasing Profits Collectively Reported by US-Controlled Subsidiaries to Four Tax Havens as Percentage of GDP, 2004 and 2012

Sources: Congressional Research Services, Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion (2015), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40623.pdf; Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Offshore Shell Games 2017, https://itep.org/offshoreshellgames2017/.

Challenges Rooted in the Digital Economy

Tax havens are a major problem, to be sure, but the artificial shifting of profits to low-tax countries is an issue that can be addressed, at least in theory, through the application and adjustment of current tax rules. A bigger problem is the inability of our current international tax systems to equitably assess and attribute the income of digital companies owing to the very nature of their activity. Here, I will limit myself to a discussion of two key obstacles.

First, a digital company that provides services and information via the Internet can do a booming business in country A without establishing a physical presence there. (Online travel agencies and video-game distributors are just two examples.) Yet international rules allow country A to tax the business income of a foreign-based company only if the business has a “permanent establishment”—a registered subsidiary or physical presence of some sort—in country A.

Second, many of the big actors in the digital economy, including Google and Facebook, have adopted multi-sided business models in which the main source of revenue is not payments from users but user data, which creates value through other business activities, such as targeted advertising. Unfortunately, there is no practical system for assessing the value of this user data for the purpose of taxing corporate income. If the business entities that trade in and profit from the data are not located in country A, then there is no business income for country A to tax, even if the source of revenue and profit is data provided by users residing in country A.

This scarcely seems an acceptable state of affairs in a world where (as the Economist declared in September 2017), the “most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data.”

The Elusive Goal of International Reform

A pamphlet titled Motto shiritai zei no koto (Tell Me More About Taxes), published by the Japanese Ministry of Finance, refers to taxes as “dues for membership in society” and correctly states that the guiding principles of good tax policy are “fairness, neutrality, and simplicity.” Surely a system that allows hugely profitable, ever-expanding global tech firms to avoid taxation, thus conferring on them a huge competitive advantage over conventional businesses, is neither fair nor neutral.

Of course, the world’s tax policy makers are not indifferent to these problems. In 2012, the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project was launched at the initiative of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, long a major force for international tax coordination. In 2013, it adopted a 15-point agenda and began deliberating concrete reform measures. The first and most closely watched item on that agenda was Action 1: Addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy.

In October 2015, the BEPS Project issued final reports for each action item. Most of these reports set forth concrete policy recommendations for preventing tax avoidance, which are now being implemented at the national level. However, when it came to the all-important Action 1 (taxation of business activity in the digital economy), the report limited itself to analyzing the problems and presenting the major options under discussion. (Since then, deliberations on Action 1 have continued under the Inclusive Framework on BEPS.)

Current Trends and Future Prospects

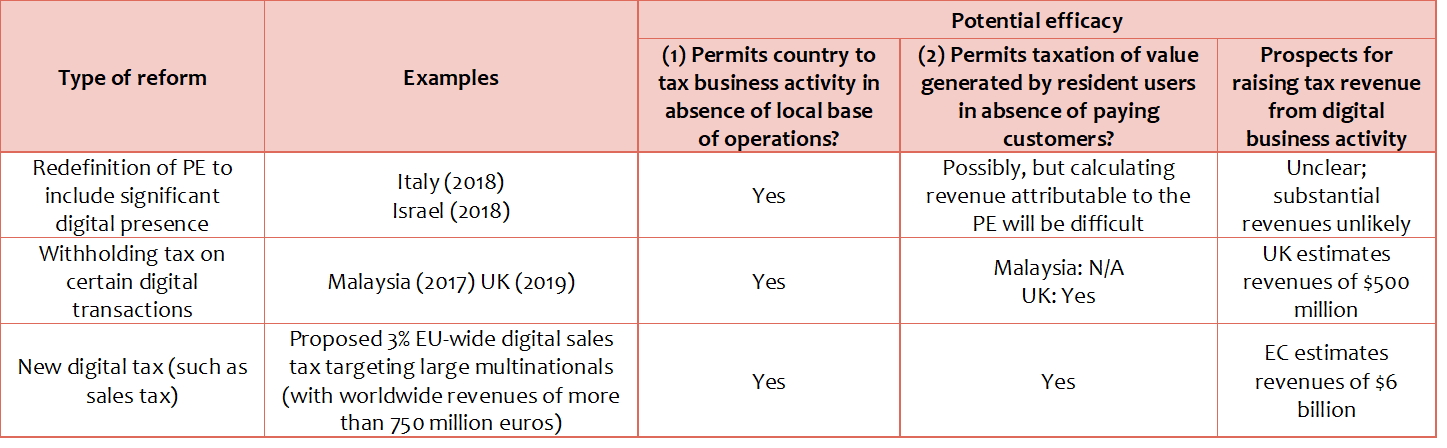

In the absence of an international agreement for taxing the digital economy, the EC and a number of individual countries began pursuing their own initiatives. The following is a brief summary the major developments on this front. For the purposes of brevity, I have assessed them primarily in relation to the two issues discussed above, although these reforms face other challenges as well.

Table 1. Digital Tax Reforms at the National/Regional Level

The EC was originally hoping to secure unanimous agreement for its proposed EU-wide 3% digital sales tax by the end of 2018, but in late November the initiative was rejected by Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. The next major opportunity for progress may come in June 2019, when the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors meet in Fukuoka during a G20 summit hosted and chaired by Japan. In 2020, the OECD plans to publish another final report on BEPS Action 1.

Google was established in 1998, and the iPhone was launched less than a decade ago, in 2007. The digital economy has evolved and expanded at breathtaking speed, and the rules of taxation have failed to keep pace. The situation right now is helter-skelter, as hard-hit “countries of consumption” begin to act unilaterally. But because the domestic and economic pressures vary greatly from country to country, the outlook for a global accord remains unclear.

Although the proposed EU-wide digital sales tax was rejected, the very fact that such a plan was formulated and widely embraced could create an inducement for collaboration on a more acceptable agreement under the OECD. And, of course, if the EU initiative ends up being implemented at some point, other countries are likely to follow suit.

Japan has a special role to play in the negotiations ahead. It is both a country of consumption—home to millions of users who generate value for US-based tech firms—and a “country of residence” with its own expanding multinational tech firms. Japan must balance these interests as it stakes out its own position on international tax reform. But it also has a duty to lead the way toward fair solutions that benefit the international community as a whole, not one country at the expense of others.

Reference

Galloway, Scott. The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2017)