- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

A Small but Socially Responsive Company: Soken

March 28, 2017

The Soken Group is a small enterprise of around 60 employees engaged in interior design and finish work. Founded in 1967 by Yasuhiro Ariyoshi, Soken has been providing high-quality finishing services for half a century. Applying the knowhow of a subsidiary specializing in custom cabinetry, Soken frequently undertakes jobs requiring woodworking expertise, such as renovating historically important buildings and creating interior finishes for art museums. As a small company, though, it has seen its business fortunes rise and fall with market fluctuations, and it has not always been easy to find good clients—especially in its early years.

The Founder’s Journal

When the founder passed away suddenly in August 2004, his son, Norihiro, found himself catapulted into the position of company president. The junior Ariyoshi was Soken’s sales manager at the time, so he was familiar with the company’s operations. But he had no management experience and no one to turn to for guidance or advice.

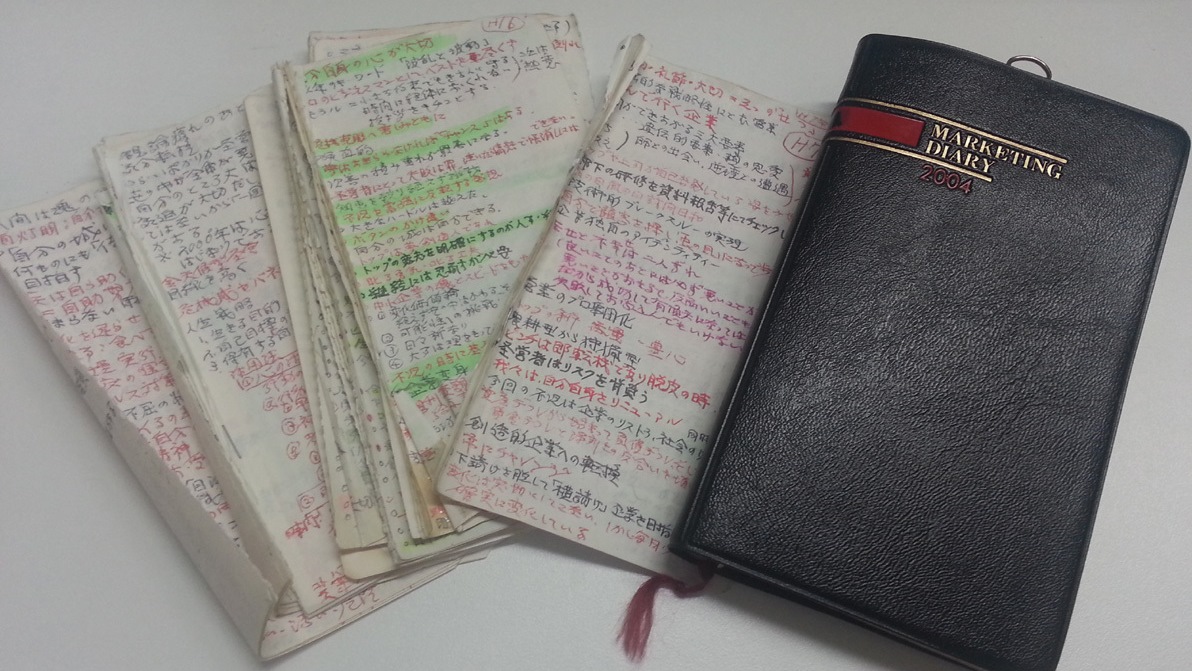

For two years, Norihiro did all he could to keep the company going, after which time he remembered that there was a safe in the office that had remained closed. Hiring an engineer to have it opened, he found a journal inside containing notes handwritten by his father on insights into the meaning of work and how to run a business. These were personal memos and maxims jotted down by a man confronted with the difficult—and often lonely—task of managing a small company. Having himself struggled for two years to run a company, Norihiro found his father’s words to be a wellspring of inspiration. This was the guidance and management advice for which he had been thirsting.

One entry made a particularly strong impression: “January 1. Trees have entrusted their precious lives to us. So let’s be sure to treat them with the care they deserve.” This was an insight that evidently occurred to his father on New Year’s Day. There was nothing unusual about the comment, especially coming from someone who regularly works with wood. But it was an idea that had never occurred to the younger Ariyoshi. But now that he thought about it, he remembered his father repeatedly noting the need to put leftover materials to better use. He had always thought that his father was just being frugal and was interested in cutting costs. But he realized that there was a deeper reason for the remark. This prompted a rethink on how wood should be used to enrich and improve people’s lives.

Engaging with Children in Institutional Care

One concrete form of contribution that Ariyoshi hit upon was to address the needs of children requiring institutional care due to the death or neglect of parents. He visited the local government office in central Tokyo, but was told there was not much he could do. He was introduced instead to Shin Nihon Gakuen, a social welfare foundation operating a facility in the neighboring city of Kawasaki.

He visited the orphanage, introduced himself and his company, and conveyed his desire to be of service to the children living there. With Christmas coming up, he was told that the home was looking for a “tree” that could be assembled and decorated safely during the holiday season and stored away without taking up much space during the rest of the year.

Soken artisans built a knockdown Christmas tree with thinnings, coated it with natural, toddler-safe paints, and presented it to the facility. This launched a program of exchange between Soken and the children living at the institution, through which Soken employees gained new insights into how it could make a positive difference in these kids’ lives.

Given Soken’s field of expertise, the obvious place to start was to refurbish the building’s interior, particularly as a few minor changes could be enough to create a new image and enhance ease of use. A fresh look might also brighten up the lives of the children and the staff, and inviting their input would be an opportunity for them to give shape to their own ideas, enhancing their attachment to the facility.

Another benefit of this project was the familiarity the children gained with the concept of work. They would one day need to move out of the facility and support themselves, but they had little idea of what gainful employment actually entailed. The only adult role models for many of these children were the staff members they saw on a daily basis.

So the Soken employees who helped redesign the interior were a novel presence. They developed a friendship with the kids through their repeated visits and asked them what they wanted their “home” to look like. The children gradually opened up with requests, coming to feel that their input could have a real impact. The Soken members also invited the kids to help out with the refurbishing task, giving them a taste of both the joys and hardships of working. Following renovation, staff members note that the kids have visibly become more concerned about keeping the room clean.

The children were not the only ones affected by the experience; it proved quite enlightening for the Soken workers as well. Interior finishing usually involves a division of labor, with different specialists handling various phases of the work. Since flooring is often completed before other tasks, those responsible rarely get to meet the client, who normally comes to check only as the work approaches completion. But at Shin Nihon Gakuen, the renovation took place while the kids continued to use the premises. So they would come by on a daily basis to see if any progress had been made. They would see the new floor materializing before their very eyes and exclaim, “Wow, that’s fantastic. It’s like magic!” Unaccustomed to this kind of positive feedback, the usually reticent workers became talkative, inviting the children to try their hand at a variety of tasks.

New Revelations through Exposure to Work

Soken’s engagement with Shin Nihon Gakuen thus had tangible benefits both for the shelter and for the company, whose workers rediscovered the value of their work. Indeed, experiences like these are often cited as some of the most rewarding aspects of working life.

This recognition led to additional initiatives to provide opportunities for children, particularly those living in institutional environments who find it difficult to envision a promising career, to engage in meaningful work. This was the motivation behind Soken’s decision to invite interns to the workplace. The presence of these young workers led to benefits similar to the engagement with Shin Nihon Gakuen, leading to fresh insights into the value of one’s own work and the mission of the company.

But it also produced a bit of confusion, as interns were accepted without first confirming what they wanted to learn on the job. In some cases, Soken was unable to provide the kind of learning experience the young workers had hoped to gain.

Soken thus turned to partners for help, notably Bridge for Smile (B4S)—a nonprofit that helps youths who have grown up in children’s homes to live on their own “with dreams, hope, and smiles without giving up the possibility of a promising future.” B4S claims expertise in communicating and working with childcare facilities and the kids who live there, so it was the perfect organization to turn to in identifying the interns who would benefit most from spending time at Soken. The partnership also benefited B4S by increasing the number of participating companies in its vocational experience program and its follow-up networking initiative for those who have left institutional care.

Soken became the employer of choice for summer and winter interns who were interested in learning about design, who were confident about their drawing skills, who had an interest in woodworking, who were adept at working with their hands, who hoped to make videos, and who enjoyed physical work. Soken employees, too, looked forward to welcoming these youths, as their stay at the company offered an opportunity for “learning by teaching.” These exchanges offered opportunities for rediscovering the value of work, for fostering pride in one’s skills, and also for enhancing one’s powers of observation.

Professional Work as a Public Service

The desire to be of service to society also motivated President Ariyoshi to offer the company’s services in the wake of the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. He visited the affected areas with fellow Soken employees to explore ways to contribute to the recovery and reconstruction effort. On their first visit, though, they were simply overwhelmed by the scale of devastation and ran about in confusion, earning the censure of one local community leader. Ariyoshi persisted, however, to ascertain what the residents needed and returned a week later to undertake repairs so that damaged homes would be livable again. They performed the tasks in which the company had professional expertise on a pro bono basis, working closely with the community leader who had initially chastised them.

The week spent volunteering in Tohoku led to a number of new discoveries. An employee who had seemed withdrawn at work, for instance, turned out to be a very good listener able to get local residents to open up and talk about their needs. Such unanticipated benefits encouraged Ariyoshi to offer pro bono services again in the wake of the April 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes. From its unique perspective as a specialist in interior design, the company has been actively communicating what it has learned from these experiences through its blog (Japanese only).

Enhancing CSR through Trial and Error

Soken’s CSR initiatives, undertaken on a companywide basis under Ariyoshi’s leadership, have spawned a number of new partnerships and broadened the company’s possibilities. One important encounter during Soken’s involvement in post-3/11 reconstruction was with Ishii Zoen, a Yokohama-based company specializing in landscape gardening and general construction work. Being a likeminded firm, the company has become a key business partner with whom Soken can shares ideas about management, employee relations, and the social role of private businesses.

Soken’s aspirations to become a socially responsible company, though, have not shielded it from workplace accidents. One of its employees was involved in a serious incident in January 2016 (the employee returned to work in May after a period of rehabilitation). Rather than downplaying the ordeal, it used social media to actively disclose the details, including the findings of an investigation into the causes and the preventive measures taken since then. Inviting input from both employees and outside experts, the company is now taking steps to create “Japan’s safest workplace.”

Ariyoshi and his Soken colleagues are exploring a full range of options—including even the possibility of suspending existing operations—to enhance the company’s CSR and better meet society’s needs. Implementing a number of concrete initiatives and making improvements as needed are surely activities that even a small company like Soken can undertake. The real test is to implement them on an ongoing basis. This will require a vision for the company’s role in society that is broadly shared among the employees. Soken is living proof that the fulfillment of social responsibilities need not be the exclusive domain of large corporations.

As a small company that is often called on to perform subcontracting work, Soken is well aware of the contradictions and opaque practices of the industry in which it operates, such as those related to waste disposable. Persuading others to change bad habits can be very challenging; in fact, it would make much more business sense not to make any waves. Turning a blind eye to these practices, though, would impact negatively on employee morale, sapping the company of its dynamism. Ariyoshi thus chose the narrow path of addressing these issues head-on, by which he hopes to ensure the company’s future growth.

As Soken’s example pointedly illustrates, CSR involves much more than creating a dedicated department or publishing a sustainability/integrated report. Through trial and error and drawing on its strengths as a small company, Soken has made inspired and ongoing efforts to enhance its CSR in responding to society’s needs.