With a fiscal deficit more than twice its gross domestic product and a rapidly aging society, Japan needs a Plan B to limit the economic fallout in the event of a fiscal meltdown, warns economist Motohiro Sato.

* * *

How seriously should Japan take the danger of fiscal collapse? This has recently become a hotly debated issue in Japan.

On one side are those who rightly point out that Japan’s sovereign debt is already more than 200% of gross domestic product and that social security expenditures will only further grow as the population continues to age. Yet an equally vocal camp calls the threat greatly exaggerated. Give Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s growth policies a chance to work, we are told, and all will be well; those in this camp maintain that the economists pointing to the dangers of fiscal insolvency are just crying wolf.

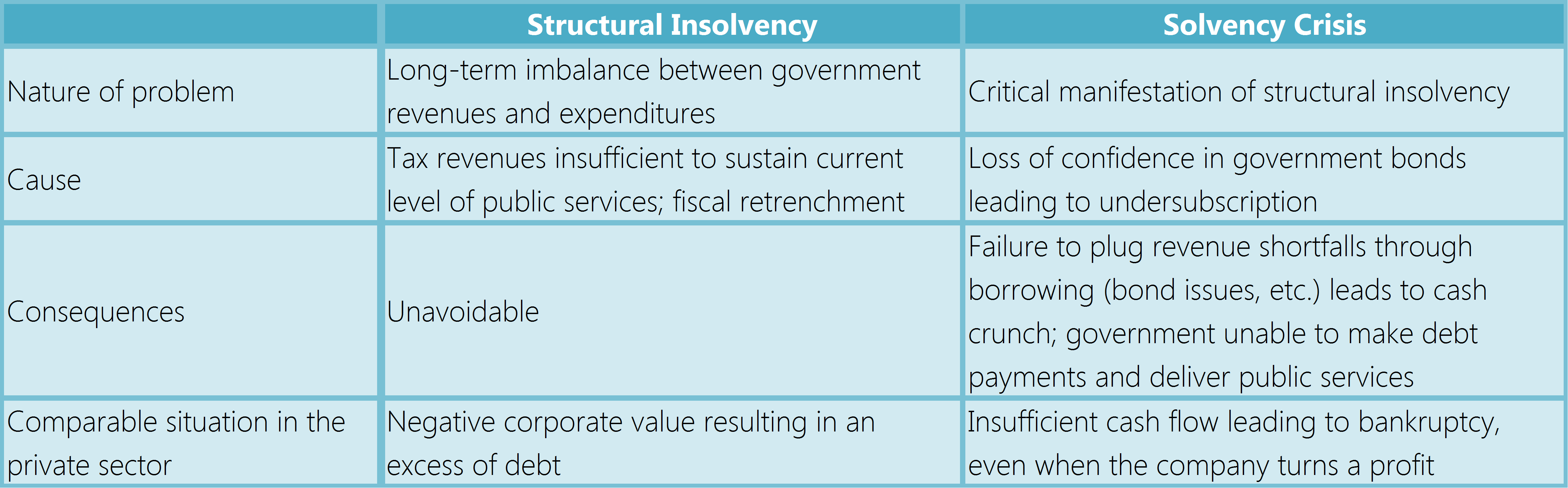

Of course, Japan is not headed for the kind of bankruptcy seen in the business world, where insolvent companies are liquidated and dissolved. However, there is little doubt that the Japanese government is in a state of structural, or latent, insolvency in the sense that it is on an unsustainable financial footing. Unless something is done to rebuild government finances, this structural insolvency will eventually erupt in the form of a solvency crisis, with very serious repercussions for the nation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Two Types of Fiscal Insolvency

Portrait of a Japanese Debt Crisis

The event that would signal the beginning of a full-fledged fiscal crisis in Japan would probably be an undersubscribed issue of Japanese government bonds (JGBs)ーthat is, a refusal by Japanese financial institutions and other institutional investors to purchase all the bonds issued at the price needed to make up for a budget shortfall. (Under the current government’s quantitative easing policy, the Bank of Japan purchases about ¥80 trillion in JGBs annually from commercial banks, but this cannot go on indefinitely.) In the worst-case scenario, the government would find itself without sufficient funds to meet its financial obligations, including debt payments and social security benefits.

But the impact of a sovereign debt crisis would not stop there. In Japan, most of the prefectural governments are heavily dependent on subsidies from the central government, particularly under the so-called local allocation tax. In addition, the prospect of receiving such cash transfers in the future enhances the creditworthiness of the local governments and serves as a kind of guarantee for local bonds. A fiscal crisis at the national level would trigger a chain reaction of crises at the local level.

Once in the midst of such a crisis, the government’s options would be limited. It may default on its bond payments. Russia did this in 1998, as did Argentina in 2001. However, Japan is in a different position from those countries. Almost all Japanese government debt is held by domestic banks and other large Japanese institutional investors. This practice has helped support a stable bond market and finance ever-burgeoning government expenditures, but it means that a government default would hit those institutions very hard, quite possibly triggering a financial market meltdown. In the end, the Japanese economy and the Japanese people would bear the full brunt of the default.

The Least Bad Option

The second option would be to have the Bank of Japan buy up all government bonds. (At the moment, the BOJ is prohibited by law from buying bonds directly from the Japanese government, but the Diet could amend the law.) Unfortunately, such a measure is likely to lead to runaway inflation. In the aftermath of World War II, the BOJ’s massive purchase of government bonds to finance economic reconstruction resulted in an expansion in the money supply that triggered hyperinflation. To be sure, the high inflation rate erased much of the government debt accumulated during World War II. But hyperinflation takes a brutal toll on people’s economic circumstances.

The only option other than default and hyperinflation is rapid fiscal retrenchmentーa painful and politically perilous process. The government has outlined targets for gradual fiscal reconstruction, but in a debt crisis, the markets will demand drastic action. For example, after the Greek debt crisis of 2010, the government in Athens was obliged to implement deeply unpopular austerity measures in the form of consumption tax increases and cuts in social spending. Measures of this sort has a direct impact on people’s living standards.

For a real-world example a little closer to home, we need look no further than the city of Yubari in Hokkaido. In 2007 the municipal government, which served a community of about 13,000, declared itself insolvent with debts totaling more than ¥38 billion. Yubari was designated a “municipality under rehabilitation,” and the central and prefectural governments took effective control of its finances. The city was forced to cut the number of municipal employees in half, slash public salaries, and make sharp cuts in public services. It downsized the municipal hospital and closed a number of elementary and junior high schools. It raised the tax on kei light motor vehicles to a rate some 50% above the norm for Japanese municipalities, began charging for garbage collection, and raised user fees at public facilities.

Of course, preventing such a crisis to begin with is the best option of all. Plan A should be a fiscal reconstruction program strong enough to avert a fiscal crisis. But in the event that Plan A should fail, we need a Plan B outlining measures to contain the crisis and minimize the fallout. For example, while people may agree on the need to reduce spending, they tend to disagree on the particulars. Rather than risk a political impasse in the midst of a fiscal crisis, our policymakers should draw up a comprehensive plan in advance to pave the way for swift rehabilitation.

Containing the Crisis

A fiscal emergency plan can be divided broadly into two stages. Stage 1 consists of measures to limit the impact of a cash crunch and control the immediate damage. This includes the designation of special accounts from which reserves can be withdrawn and a list of budget items for which disbursement can be delayed or withheld with a minimum of disruption.

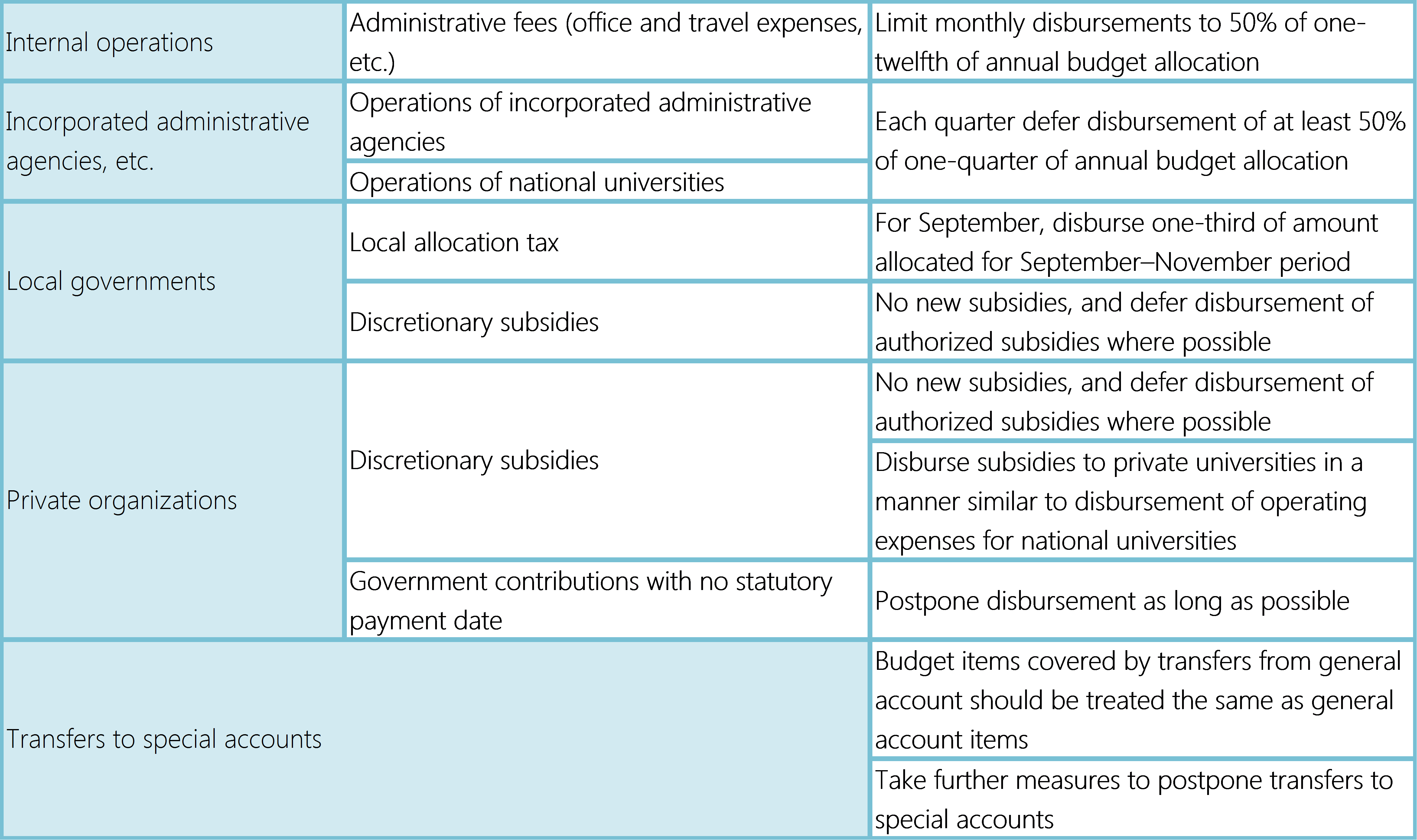

A list of this nature was actually drawn up in the fall of 2012, when Japan was heading for its own “fiscal cliff.” The Democratic Party of Japan was in power, but the House of Councillorsーthe upper houseーwas controlled by the Liberal Democratic Party, which refused to approve a special bond issue needed to avert a budget shortfall. To cope with the crunch, the government systematically limited or delayed disbursement for low-priority budget items, including local allocation tax transfers to the prefectures and internal operating expenses for governmental and quasi-governmental agencies, in accordance with guidelines adopted on September 7, 2012 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Guidelines for Limiting Budget Disbursements, September 7, 2012

The plan for stage 1 should also provide for emergency bailout funds to protect the nation’s private financial institutions from the impact of plummeting government bond prices. These measures can help calm markets and avert a panic. For more detailed recommendations, including measures to prop up local banks, see the Tokyo Foundation policy proposal “Zaisei kiki ji no seifu no taio puran” (Government Plan for Responding to a Fiscal Crisis; in Japanese), July 2013.

Rebuilding Confidence

Stage 2 should focus on stanching the bleeding through the adoption of a fiscal retrenchment plan in the form of tax increases and spending cuts. To ensure that austerity measures are appropriately geared to the severity of the crisis, policymakers should draw up several alternative retrenchment plans tailored to a range of scenarios. The government must prepare a suitable deficit-reduction plan that it can quickly show to investors to calm the bond market. The plan should itemize the tax increases and spending cuts needed to cut the fiscal deficit at both the national and local levels, listed in order of precedence.

The stage 2 plan should prioritize and categorize public services by importance, ensuring that vital services are maintained. This is to prevent political dynamics, rather than need, from dominating the decision-making process. In the wake of the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, politicians seeking resources to finance post-disaster reconstruction sought cuts in the child allowance (aware that families with children have relatively little electoral clout in Japan), rather than pensions or public works. A process comparable to triage must be performed in advance to avert this kind of scenario. The minimum allocations necessary for national defense, law enforcement, and disaster relief must naturally be maintained. In the area of healthcare, priority should be placed on such critical services as emergency care, perinatal care, and dialysis. Meanwhile, the central and local governments should be prepared to sell off any unutilized land or buildings in their possession.

Finally, the government needs to draw up an outline of post-crisis rules for long-term fiscal sustainability, together with a roadmap of fiscal and tax reforms, to restore the confidence of investors. The rules, aimed at steady reduction of the deficit, should encompass both top-down restraints on overall spending and mechanisms to adjust allocations on the basis of policy and program evaluations. Only in this way can we reassure the market of the sustainability of government finances and restore confidence in government bonds.

Of course, no one can accurately predict what will happen in a crisis. It may not be possible to rebuild exactly according to plan. But advance planning can at least provide guidelines for rehabilitation. Instead of maintaining the fiction that “it can’t happen here,” let us adhere to the core principle of risk management: Hope for the best but prepare for the worst.