- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Identifying Materiality through Stakeholder Engagement: Sompo Japan Nipponkoa

June 29, 2015

Sompo Japan Nipponkoa is a nonlife insurance company that volunteered its office work expertise in support of areas affected by the March 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. It is also unique in emphasizing dialogue with stakeholders to identify key issues for its CSR initiatives. The following is from the section on "Businesses Driving Positive Social Change" of the Tokyo Foundation's CSR White Book 2014.

* * *

Insurance is a scheme by which subscribers pay fixed premiums to prepare for future risks and unforeseen accidents, and it can be regarded a system of mutual assistance. Some insurance schemes are run by the government, including those for healthcare, pensions, unemployment, and seafaring workers. But others, such as life insurance and nonlife insurance, are generally the responsibility of the private sector.

The irony for insurance companies like Sompo Japan Nipponkoa and their employees is that it is during disasters, accidents, and other unwanted situations for their subscribers that they become most useful in society. This is because insurance companies perform their most important function—making payments—when subscribers are in the worst of situations.

This was especially true in the wake of the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, when more than 3,000 Sompo employees were mobilized to meet the needs of those affected. The company had two key objectives: (1) to make insurance payments as quickly as possible and (2) to provide uninterrupted services, such as for new contracts. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster it sent support staff to the affected areas, set up an emergency response headquarters, conducted assessments of the situation on the ground, and addressed customer inquiries. The number of cases it handled was the largest in the company’s history.

For victims of a disaster, the money they receive from their insurance company is the first step toward rebuilding their lives. Seeing people doing their best to face up to a difficult situation gave many Sompo employees a renewed appreciation of the role and raison d’être of an insurance company.

Offering Expertise

The company’s exposure to the disaster zone prompted a reassessment of its work in other ways as well. Working as volunteers in the affected areas and collecting donations were obviously quite helpful, but Sompo employees could make an even bigger contribution by offering their professional expertise, honed in the course of their daily work.

One such skill is the ability to process very technical paperwork, which is part of a nonlife insurer’s work of collecting premiums and making payments. Like banking and life insurance, this involves handling customers’ valued assets, so mistakes are not permitted. A huge volume of forms must be processed and accidents dealt with on a daily basis. A disaster on a scale of the Great East Japan Earthquake requires sophisticated and precise workflow to assess the damage and make payments. This might appear to be a matter of course for an insurance company, but predicting peak administrative volume and creating and continually improving the workflow for error-free operations requires great skill.

One example of how the company used its expertise was its administrative support for CANNUS Tohoku, an NGO operating along the Miyagi coast near Ishinomaki. CANNUS is a national organization headquartered in Fujisawa, Kanagawa, that registers and dispatches volunteer visiting nurses to provide medical and nursing care in the local community.

CANNUS Tohoku was set up following the March 2011 earthquake and has played a valuable role in providing a range of physical and mental healthcare services for the elderly. With volunteer nurses focused on meeting the caring needs of residents in the community, though, the CANNUS office faced a backlog of paperwork, resulting in failures to fully share information, especially when work was handed over to new volunteers. With its resources overstretched, the NGO was unable to keep systematic records of what the community lacked, hindering efforts to petition the authorities for fresh supplies. Visiting nurses often experienced long delays before their travel expenses were reimbursed, and opportunities to apply for grants came and went for lack of familiarity with the application procedures.

CANNUS Tohoku was exactly the kind of organization that could use Sompo’s administrative expertise. After confirming this hunch, the insurance company dispatched 10 employees to work at the local office for three months.

The Sompo staff reorganized CANNUS Tohoku’s workflow. The employees even provided training in such areas as creating a user database, identifying local healthcare and welfare needs, using report forms and spreadsheet software, and applying for grants so that local workers would be able to handle these tasks on their own once Sompo left.

Such assistance ensured the sustainability of CANNUS Tohoku’s operations and enhanced the usefulness of its services to the local community. It also had the effect of heightening Sompo employees’ awareness of their own skills as office professionals—expertise that could be shared to assist the reconstruction of disaster-hit areas. Traveling to tsunami-affected areas to help clear debris, which many volunteers from around the country did, was not only way to help; they realized that they could put the skills they had acquired on the job to make an important contribution. They also gained a deeper understanding of the value of working as a group. These insights will no doubt have a great impact on their careers, as they now have a fuller grasp of the significance of their jobs.

Attendance at the Rio Summit

The roots of Sompo’s CSR initiatives go back to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit), held in Rio de Janeiro from June 3 to 14, 1992. While the summit’s Declaration on Environment and Development called for “new levels of cooperation among States, key sectors of societies and people,” most participants from Japan were from the government. One of the few representatives of Japan’s corporate community—and the only chief executive—was Yasuo Goto, then president of Yasuda Fire & Marine Insurance (which later became Sompo Japan Nipponkoa).

The Earth Summit was held just before the annual general shareholder meeting season, so most business leaders chose not to attend. Goto, however, was very interested in the summit, believing that the environment and sustainability were crucial issues for both society and business.

Yasuda Fire & Marine became well-known in Japan for its purchase of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers , which was put on public display as a way of giving something back to society in a way other than through insurance payments. Later, the Nature Conservancy, a US conservation group, visited the company to meet the executive who had bought the painting, an encounter that deepened Goto’s interest in environmental issues. Believing firmly that virtue and strength are keys to success as a company, Goto attended the Earth Summit and oversaw the establishment of the Global Environment Office at Yasuda to deal with sustainability issues.

Yasuda was not just a company with principled leadership but also the second largest firm in the industry. In the early 1990s, the insurance sector was strictly regulated, and differentiating oneself from one’s competitors in terms of products and pricing was quite difficult. Yasuda’s focus on environmental issues, therefore, was an attempt to offer something unique, no doubt based on the conviction that customers would rather choose an insurer that valued the needs of society and its future.

A Groupwide Effort

CSR initiatives are often launched by top management, and they tend to lose steam following a leadership shuffle. This was not the case at Sompo, however, as these activities were pursued under the principles of “full-participation, steady and continuous progress, and acting with initiative,” which are still adhered to today. In 1993, the year after the Earth Summit, the company began engaging with civil society by launching a volunteer group for employees called the Chikyu (Earth) Club and organizing public seminars on the environment.

While the company’s CSR initiatives began with a focus on the environment, they later came to cover a full range of issues. They were undertaken on a groupwide basis with the participation of all employees, who discussed concrete CSR case studies. Conducting such detailed and repeated discussions within and without the company became a matter of routine, a practice that continues to this day.

There is even a section concerning CSR initiatives in employee evaluation forms, with staff and their managers being called upon to discuss this topic. The intention is to get employees thinking about these issues, however, for the substance of such discussions is not used in the actual evaluation.

Assessing Stakeholders’ Expectations

In integrating its CSR initiatives and business operations, Sompo focuses on what it calls “five material issues.” The first is “providing safety and security” to society, which refers to innovative services that meet customers’ safety and security needs by mitigating various risks. The second is “tackling global environmental issues, including climate change.” In addition to dealing with climate risks on its own through “adaptation and mitigation,” Sompo also partners with groups in other sectors to develop new solutions. The third is “providing sustainable and responsible financial services” to address social issues. The company promotes responsible investment incorporating ESG (environmental, social, and governance) criteria and develops financial and insurance products and services to help resolve various issues. The fourth is partnering with NGOs to help build a sustainable society through “community involvement and development.” And the fifth is “developing human resources and promoting diversity” to build a stronger organization. By creating dynamic workplaces where diverse human resources can fully apply their skills, Sompo is encouraging the development of employees who can make valuable contributions to society through their work.

These five “material issues” may not be unique to Sompo, but what sets them apart is the process by which they were arrived. They were not unilaterally issued by the CSR or corporate planning department nor by top management. They are the result of a three-step process consisting of (1) conducting analysis and implementing a questionnaire survey based on the ISO 26000 guidelines for social responsibility; (2) holding dialogue with experts; and (3) identifying specific issues.

During the first stage, social issues as outlined by ISO 26000 were mapped out, and a questionnaire survey was conducted to assess what the public expected from Sompo.

ISO 26000 was developed through discussions among a broad range of stakeholders in both developing and developed countries, including consumers, governments, private companies, organized labor, NGOs, and academic institutions. Unlike ISO 14001 for environmental management systems, ISO 26000 is not focused on certifying compliance with a set of standards but offers guidelines for the integration of corporate resources to enable companies to efficiently fulfill their responsibilities to stakeholders.

Importance is given in ISO 26000 to how organizations think about and implement strategies to deal with key issues. For human rights, for example, companies need to examine whose human rights are at stake and what the problems are, then use the guidelines to identify the most significant human rights issues for their respective organizations.

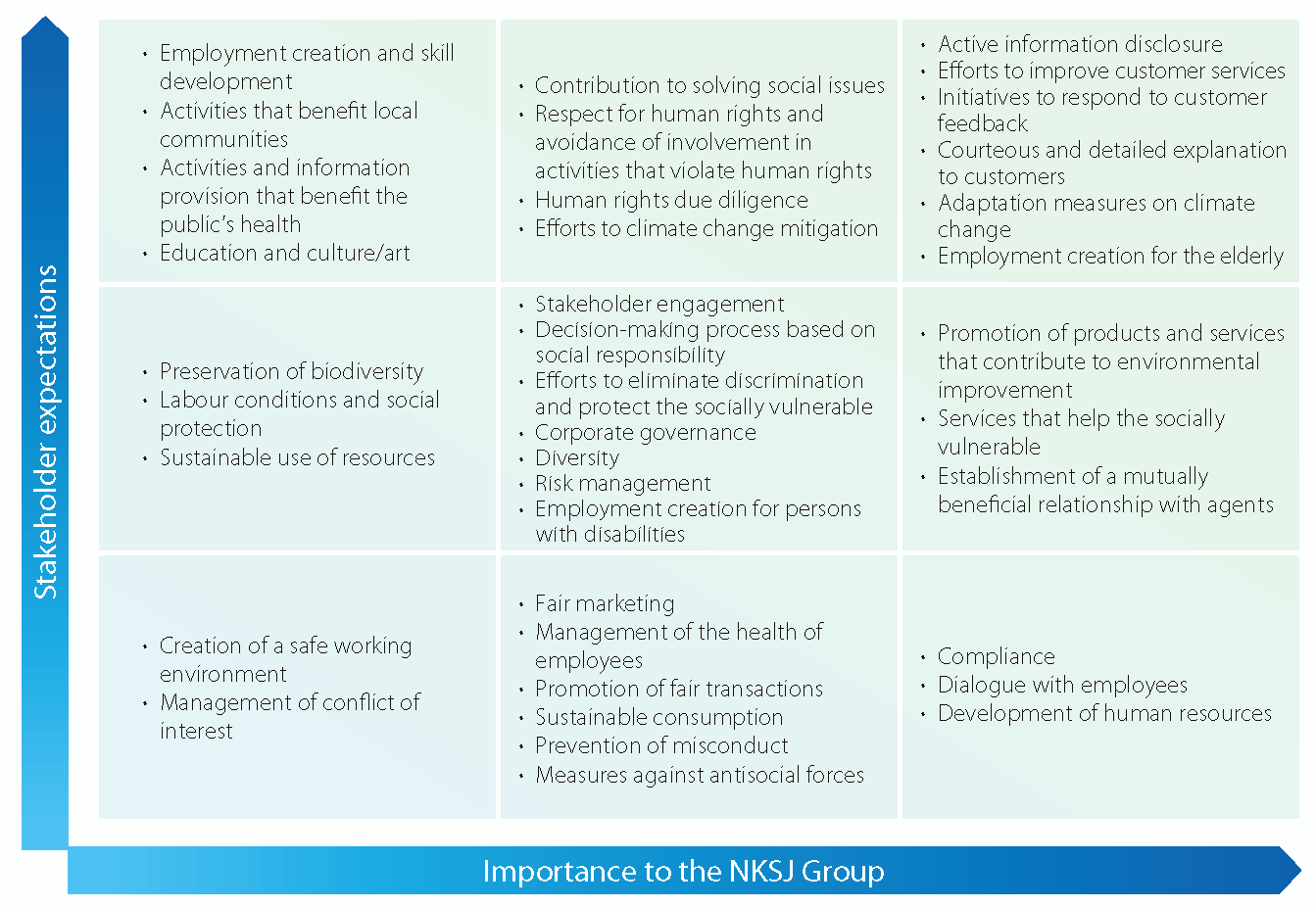

Sompo used ISO 26000 to identify possible focuses for its CSR initiatives, after which it conducted an online questionnaire (answered by 1,032 people) to discover the areas where stakeholders had high expectations of the company. It also analyzed which areas had the greatest significance for their business operations. Figure 1 is a mapping of “stakeholder expectations” and “importance to the NKSJ (now Sompo Japan Nipponkoa) Group” along the vertical and horizontal axes, respectively.

Figure 1. Analysis of Material Issues Based on ISO 26000

Note: NKSJ Group refers to Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Holdings (since September 2014).

Reaching Out to Civil Society

Once this was done, Sompo moved to stage two: dialogue with outside experts. Top experts from the environmental and civic sectors were invited for discussions with not just members of the company’s CSR department but also staff at all levels, from senior management to newly hired employees.

This process has enabled the company to develop human resources who are fully aware of and are ready to meet the needs of society. The feedback received from outside experts during the process of identifying material issues is included in the company’s 2012 CSR report: NKSJ Holdings’ Corporate Responsibility Communication 2012 . Examples include the following:

In Japan after the Great East Japan Earthquake, work to address global warming slowed down, but natural disasters, like the Thai floods, are likely to become more common from now on. So climate change will be a key issue for insurance companies. I’d like to see the NKSJ Group maintain its broad perspective and take progressive measures while looking one step—or even slightly less than that—ahead. (Junko Edahiro, environmental journalist and chief executive, Japan for Sustainability)

Regarding the “provision of security and safety,” I think there are two basic ways to deliver such value: (1) through existing services and (2) through newly created services. Sompo’s Eco & Safety Drive, for example, is a well-established service in Japan. But in developing countries, where traffic fatalities are likely to become an increasingly serious concern, there will be a growing need for such preventive services. (Hideto Kawakita, CEO, International Institute for Human, Organization, and the Earth)

Dialogue with outside experts has enabled Sompo to gain fresh insights into the medium- to long-term, from both the personal and corporate points of view. The broadening of understanding has extended not only temporally into the future but also spatially to conditions in other countries.

The process has also led the company to reaffirm the importance of three concepts: (1) ongoing dialogue with a wide range of stakeholders; (2) identification of broader and deeper emerging issues; and (3) actively working with society to create new value.

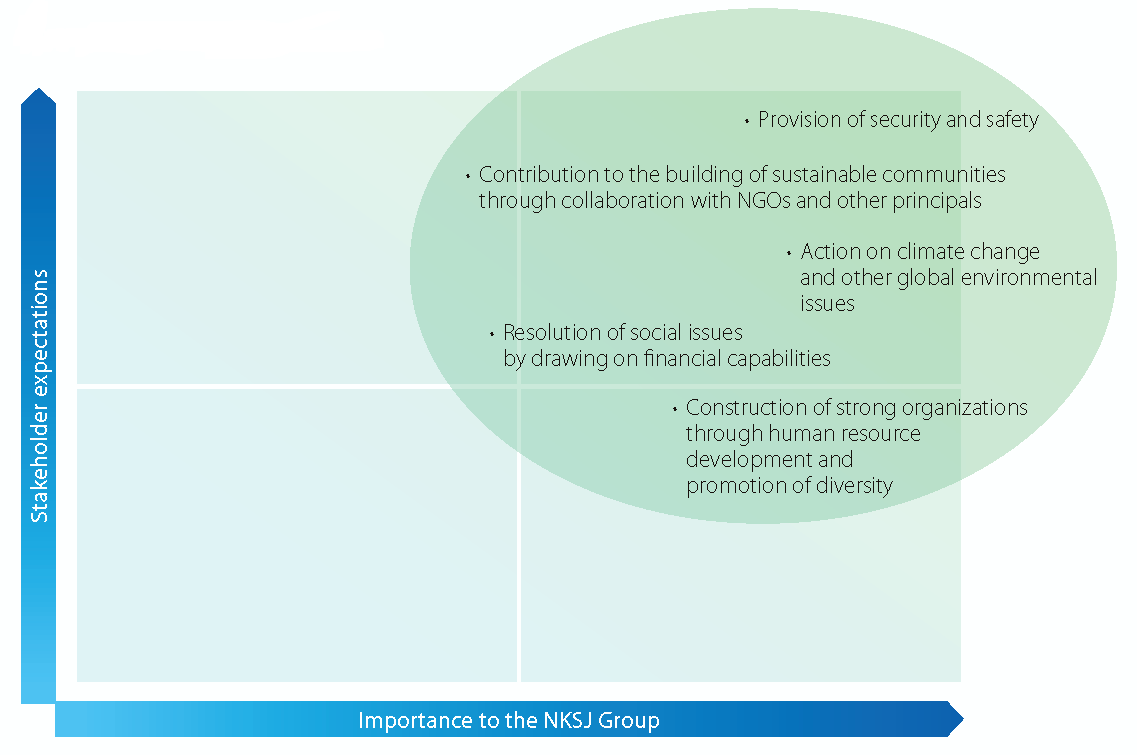

Figure 2. Mapping of Material Issues

Note: The issues were revised in 2014 and now consist of “Six Group CSR Material Issues.” (See: http://www.nksj-hd.com/en/csr/system/)

Looking Ahead

As for the third and last stage of identifying specific CSR issues, Sompo mapped the results of the first two phases using, again, the two axes of stakeholder expectations and importance to the NKSJ Group, as shown in Figure 2. Some might wonder if going through so much trouble to identify key issues is really necessary, as the same conclusions might have been reached just by reviewing the work the company performs every day.

The important point about this process, though, is not really the issues themselves; of greater significance is that it enables the company to communicate its intentions to continue its dialogue with stakeholders in reassessing its business operations. Such a stance is premised on the recognition that society’s biggest issues and their solutions are constantly changing—sometimes in unexpected ways—and involve a broad range of interdependent factors, such as the environment, public policy, economic trends and conditions, corporate behavior and business models, work styles, and household structures.

The dialogue with stakeholders and experts enables both top management and the rank and file to reflect on how flexibly they are dealing with such changes. Applying the same approaches year after year will not be enough to address emerging issues or to meet society’s expectations. The forums for dialogue are thus an indispensable part of keeping fresh and up-to-date.

Companies have a tendency to fall into a routine, and once a pattern is established, it can be difficult to change. Sompo’s foresight is in its understanding that to actively engage with society it must always look a step—even half-a-step or 0.7 steps—ahead and continue its dialogue with its stakeholders.

Meeting Social Challenges

What does the company do to address the material issues it has identified? In the field of “tackling global environmental issues, including climate change,” for example, it sees the issue not just in terms of risk management but also as an opportunity for business creation and for growth through market leadership.

The number of climate-related natural disasters has been on the rise since the 1980s, and this has had a large economic impact on many places around the globe. The probability of being adversely affected by a natural disaster is far higher in a developing country than in an industrially advanced member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (19:1 versus 1,500:1), moreover, meaning that areas that already face tough economic conditions are hit hardest by environmental issues. The insurance industry, too, is affected by disasters, which results in higher payments and premiums and can make the stable provision of insurance more difficult.

On the other hand, the situation presents opportunities for the insurance industry to create and develop new markets through a process of “adaptation and mitigation.” Through adaptation, insurance can help to reduce the damage caused by climate change, lower the risks of renewable energy initiatives; and promote innovative technologies to create a low-carbon society.

As for mitigation, Sompo is helping reduce greenhouse gas emissions by, for example, encouraging the use of recycled parts in repairing cars after accidents; reducing paper waste by promoting the shift to online contracts; introducing green procurement; and promoting the company’s Eco & Safety Drive service. The company also encourages the implementation of these measures by local insurance agents, auto repair firms, suppliers of raw materials, and other business partners and is asking its customers to take similar measures. In these ways, each department can take concrete steps in “tackling global environmental issues” in accordance with their place along the value chain.

To foster the spread of renewable energy, Sompo has developed a new type of policy to compensate for lost operating income when electricity sales from solar power generation, for instance, declines due to fire or natural disaster. This product insures against lost income and reduces the risks faced by power generating businesses, thereby supporting the spread of renewable electricity.

Helping Thai Farmers Hedge against Climate Change Risk

Another “adaptation” measure is the weather index insurance developed in 2010 to insure farmers in northeast Thailand against climate change risk. When rainfall, as measured by the Thai Meteorological Department, falls below a certain threshold, Sompo pays a fixed amount to farmers, helping to reduce the damage from drought.

Typically, local farmers borrow money before growing crops, sell their harvest to get income, and use that money to pay off their loans. When there is a drought, though, their income drops, and they do not have enough to pay back their debt. To hedge against such risks, banks are wont to raise interest rates, but this only makes things more different for the farmers; uncertainty over harvest volume is a serious problem for farmers and banks alike.

A reasonably priced insurance product to cover the risks associated with climate change was thus of great value to the local community. With infrastructure for accurate meteorological measurements already in place, weather index insurance was ready for launch. The product was offered as a package with a loan agreement, with payments designed to cover the amount borrowed.

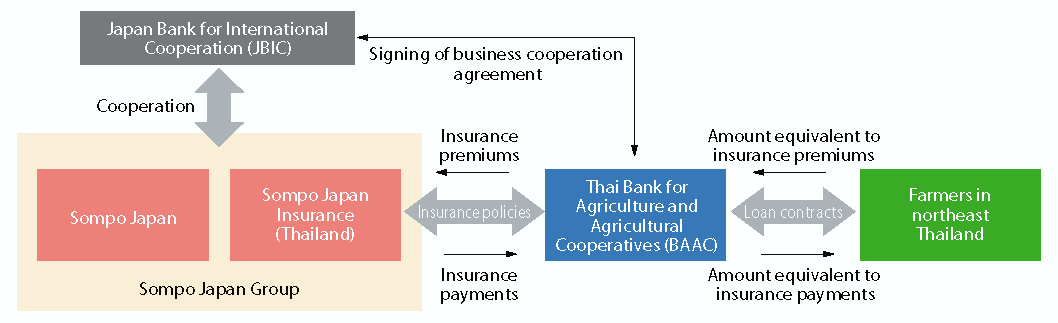

Sompo Japan developed a local risk finance mechanism and partnered with the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives of Thailand (BAAC) to offer the product to local farmers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Weather Index Insurance for Farmers in Northeast Thailand

In developing this product, the company tapped its expertise in risk evaluation and financial instruments-based risk finance. It also listened carefully to the views of local famers unfamiliar with insurance to design a simple and easy-to-understand product.

Sales of weather index insurance began in Khon Kaen Province in 2010 and expanded to five provinces the following year and to nine in 2012. The insurance’s benefits were soon recognized when farmers who had purchased the product were able to avoid a loss of income despite a drought in some areas in 2012.

Visualizing and Quantifying CSR Targets

Sompo’s CSR initiatives are characterized not only by the time-consuming process through which the material issues are identified but also for quantified targets that are set for implementing each of the five issues, which in turn generate ideas for future action through a PDCA (plan, do, check, act) cycle.

Quantification and visualization are essential components of implementing kaizen improvements in the workplace, which many Japanese companies apply to their manufacturing and sales processes. But quantification has largely remained elusive in the field of CSR. Such efforts tend to be more advanced at CSR-savvy foreign firms, with their nonfinancial reports providing not just qualitative descriptions but also quantitative data so that readers—that is, stakeholders—can have a better idea of the impact and scale of the initiatives.

Why has the effort at quantification been slow in Japan? Certainly it is not because Japanese companies do not have such skills, for they are more than capable of keeping detailed track of their manufacturing activities. The real reason might well be that most companies still think that quantification is unnecessary in CSR.

Sompo, though, is an exception. Through dialogue with experts, it is setting up key performance indicators for its CSR initiatives, as can be gleaned from the following comments published in NKSJ Holdings’ Corporate Responsibility Communication 2013 :

In my view, KPIs represent future outcomes that are desirable and that should be emphasized. The first key point for identifying your KPIs is to take a back casting approach and define your ideal future. You don’t need to pay attention to—or at least shouldn’t be bound by—whether this is something that can be measured or openly disclosed. The second key point is to continue to elaborate the KPIs. You may not be able to get everything fully prepared at the beginning because you don’t know how to obtain the data. But this is fine. All you need to do is to make sure that the KPIs will continue to evolve. The third key point is to run the PDCA cycle for the KPIs themselves. Rather than simply being content with your current KPIs, you need to be both resilient and flexible enough to make sure that they will continue to live up to the societal expectations of the day. KPIs are not goals but means. (Junko Edahiro, environmental journalist and chief executive, Japan for Sustainability)

KPIs are milestones in a long-term roadmap and should be set in such a way that they can be used as annual goals over a period of about five to seven years. Not all the annual results have to be publicly disclosed, but you should be sure to check whether the management indicators set as goals have been followed and to determine how close you were to achieving the goals and by when the goals will be accomplished. KPIs should be set high and determined by considering what impact you want to have on society through your CSR management policy. It is therefore important to set not just short-term goals but also mid- to long-term goals from a sufficiently broad and deep perspective. (Hideto Kawakita, CEO, International Institute for Human, Organization, and the Earth)

The company’s replies to these comments were as follows:

Setting our KPIs and visualizing our performance will become the engine that drives such evolution. It became very clear to me how important it is to ensure that the KPIs are designed in such a way that they will lead to increased trust and dialogue with stakeholders.” (Takaya Isogai, senior managing executive officer, Sompo Japan Nipponkoa)

Consideration about KPIs means profound thoughts on the NKSJ Group’s social responsibility. This makes it a starting point for the discussion on CSR aimed at exploring how we can maximize our positive impact on society and what goals we should set to achieve this maximization. We will advance our plan to realize the KPIs based on the advice of the two experts.” (Masao Seki, senior advisor on CSR, Sompo Japan Nipponkoa)

Creating KPIs for CSR is not an easy task, but Sompo has given it priority, no doubt considering it important in clarifying its relations to society, identifying what it can do to address social issues, ascertaining its rightful role in society, and offering fresh insights into what a private business can offer to its stakeholders.