- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Creating and Sustaining Corporate Value through Global Dialogue: Takeda Pharmaceutical

July 30, 2015

As clearly demonstrated by the rich pool of global human resources who hold key positions at Takeda Pharmaceutical—including the president and chief executive officer—the company is striving to globalize its operations and become a world-ranking pharmaceutical company. This is also closely linked to the efforts Takeda is making to place its CSR activities at the core of its corporate management.

The 2010 Patent Cliff

Corporate social responsibility is generally considered to have two main functions: the first is to enhance corporate value through positive contributions to society and the second is to protect it from various risks that could damage its reputation. The terms Takeda uses for these dual functions are “creating” and “sustaining” corporate value. All employees, from senior executives to the rank and file, are thus called upon to apply their own insights to the company’s CSR activities. This is the source of Takeda’s ability to smoothly integrate CSR into its corporate management and operations.

Takeda may be Japan’s largest pharmaceutical company, but globally it is only the sixteenth largest (in 2013), and the value of its pharmaceutical sales is one-third of market-leader Pfizer. A wave of international M&As swept through the pharmaceutical industry in the 1990s, resulting in the formation of giant, multinational companies. Since the 2000s, a different type of restructuring has emerged, with smaller companies specializing in the research and development of new drugs being bought up by larger manufacturers.

One reason that pharmaceutical companies expanded their operations was the considerable resources and time required to support the development of new drugs. The success rate of new drugs is quite low, so companies must run many research projects concurrently to hedge against the risk of failure. Human resources and money are needed to collect data and investigate the relationship to existing patents. Performing basic experiments and clinical trials also take great time.

A problem faced by many pharmaceutical companies at the time was something known as the “patent cliff.” Patents on many best-selling drugs were due to expire around 2010, at which point companies would be unable to sustain their sales and profits.

Once these patents expired, cheaper generic drugs would enter the market. This may be a welcome development from the patients’ perspective, since they would be able to purchase drugs with proven effectiveness and well-known side effects at lower prices. It would also be a boon for public health insurance schemes facing severe fiscal constraints and expanding demand for medical services. But for the pharmaceutical sector, a market dominated by generic drugs would make it difficult to secure the funds for the development of new drugs, hindering research and slowing advances in medicinal technology.

This was the impetus for the flurry of corporate acquisitions focusing on specialized, research-orientated companies, as the giant pharmaceuticals sought new platforms for the development of new drugs.

Takeda was no exception. Its patents on drugs that accounted for 100 billion in annual sales, including proton-pump inhibitor Takepron, were due to expire around 2010. To minimize this impact, the company needed to quickly bring new products to market. In 2008 Takeda purchased Millennium Pharmaceuticals for approximately 900 billion, and in 2011 it acquired Nycomed International Management for 11 trillion (prices and exchange rates at the time of merger).

Avoiding Pitfalls

The effort to globalize its operations and emerge as a leading player had the unanticipated consequence of bringing Takeda face to face with a new challenge: one that was closely linked to the industry’s relationship with society.

In March 2001, a group of 39 European and North American pharmaceutical companies took the South African government to court to protest a new law allowing the import and manufacture of generic copies of patented HIV/AIDS drugs. The companies argued that if the South African legislation went unchallenged, the international patent and intellectual property system would be undermined.

The government, along with international NGOs, countered that there were large numbers of people with HIV/AIDS in Africa and that neither individuals nor governments had the financial resources to cover the cost of treatment. They stressed that the drugs were expensive because of the patent licenses and that without them it would be possible to save many lives.

In April 2011 the 39 companies dropped their suit, partly to prevent a deterioration in their image. By then, though, the damage had been done; public opinion not just in South Africa but all over the world turned against Big Pharma, which was seen as putting business and profits ahead of human lives.

As noted above, the development of new drugs requires a huge investment, and very few new drugs actually make it to market. If a company is unable to sell their products at appropriate prices, the business will become unsustainable, and the development of the next generation of drugs will come to a halt. To that extent, the pharmaceutical companies had a right to protest.

But the legal action taken by the European and American firms sparked an outrage. The number of people with HIV is still rising, although the pace has moderated somewhat, and the disease has yet to be brought under control. The share of HIV patients is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa, with infection rates increasing in extremely poor areas—where 7 in 10 people live on less than $2 a day. If we consider that the mission of pharmaceutical companies is to contribute to the health of people around the world through the provision of medical drugs, can we still say that they were justified in launching their lawsuit?

This experience prompted many pharmaceutical companies to rethink their ties with and their mission in society as they realized that a weak relationship could become a risk affecting the company’s entire operations.

Having joined the ranks of the industry’s top global companies, Takeda, too, took this lesson to heart. Both management and labor came to the understanding that CSR activities to “sustain” corporate value meant maintaining a vigilant, risk-management watch over social issues.

Identifying Common Social Concerns

Takeda’s corporate mission is to “strive towards better health for people worldwide through leading innovation in medicine”—a goal that in itself lies at the heart of corporate social responsibility. The company seeks to improve business operations with a full awareness of how its entire value chain affects its various stakeholders and works to create a sustainable society as a good corporate citizen.

How, then, is it going about integrating its business pursuits with efforts to resolve social issues? Takeda’s approach is quite unique.

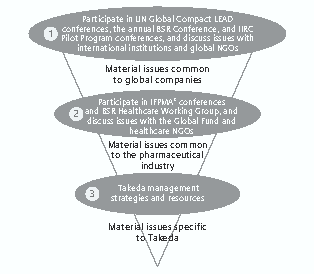

It identifies material issues common to global companies through participation in UN Global Compact LEAD conferences and annual Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) conferences, as well as by actively engaging in discussions with international organizations and NGOs (Section 1, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Three-Step Process for Identifying Material Issues

It also identifies material issues specific to the global pharmaceutical industry by participating in conferences of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) and the BSR Healthcare Working Group and conducting discussions with the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria and other healthcare NGOs (Section 2, Figure 1). This gives the company a fuller understanding of global trends by learning about the issues other companies are facing and—through participation in such trendsetting projects as those of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC)—allows it to lead the discussion between pharmaceutical companies and other industries.

These two initiatives help Takeda to identify those social issues that it is in the best position to address in the light of its management strategies and within the confines of its management resources.

The conclusions Takeda reached through this process were that it can best address two material issues. The first is comprehensive “access to healthcare” for people around the world through both its business operations and corporate citizenship activities. The second is “value chain management,” under which it advances CSR initiatives at each stage of the value chain within the core ISO 26000 framework.

The former covers corporate citizenship activities aimed at “creating” corporate value, while the latter seeks to fully integrate CSR into business operations with a view to “sustaining” corporate value.

Sompo Japan’s CSR focuses on dialogue with stakeholders and Itochu’s on an employee-based bottom-up approach. Takeda’s CSR, meanwhile, involves ongoing discussions with other global companies, including pharmaceutical firms, and their civil-sector partners to examine the role the company should play in society, the relationship it should seek to build with society, and ways to more fully integrate its business operations with initiatives that help meet society’s needs. This is the path that is enabling Takeda to both bolster its corporate vision and strengthen risk management.

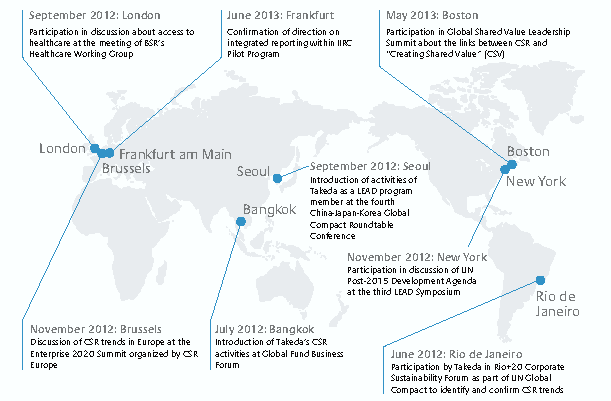

Traveling around the world to take part in various international forums may seem like a luxury (Figure 2). But this is probably the most efficient and effective way for Takeda to create and sustain its corporate value. As the fallout from the lawsuit in South Africa shows, a company risks severe damage to its business if it fails to build a strong relationship with society. Given the broad array of issues to address, there is no telling what, when, and where problems may arise. Since there is a limit to what one company can do to keep abreast of various social developments, the most rational course of action is to maintain dialogue with other pharmaceutical companies and international NGO that are keeping an eye on such changes.

Figure 2. International Conferences Attended by Takeda (June 2012 to June 2013)

Sharing Case Studies

In identifying material issues, Takeda pays particularly close attention to risks and crises that other companies have faced in dealing with society. The South Africa court case is just one example of the risks that pharmaceutical companies constantly face. Because they are engaged at the leading edge of bioethics, companies may even become the source of new social controversies.

With environmental protection rules growing tougher, moreover, new issues may come to the fore. Drugs taken by patients may find their way into rivers and seas, disrupting the food chain and posing a danger to people and other living organisms. No longer is it enough for a company to focus its attention on simply providing effective drugs to help patients recover from illness and improve their health.

There are many pitfalls for globally active companies. Those that have operated only in Japan may not fully appreciate the different values peoples in other countries have. “Sustaining” corporate value is a task requiring both managers and staff to look at issues from the viewpoint of people on the ground.

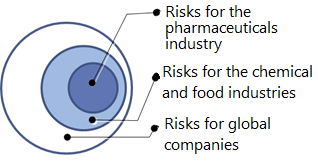

The CSR department at Takeda thus actively collects and internally shares case studies of risks and crises faced by other relevant companies around the world: those affecting global companies in general, those impacting the chemical and food industries, and those pertaining particularly to global pharmaceutical companies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Case Studies Shared by Takeda’s CSR Department

This information enables management and individual departments to assess risks more accurately. The steady sharing of information has led Takeda employees at all levels to give greater thought to the company’s relationship with society in their daily activities.

Embracing International CSR Guidelines

Takeda has thus been quite successful in integrating its business operations with efforts to address social issues. It has also made effective use of international CSR guidelines.

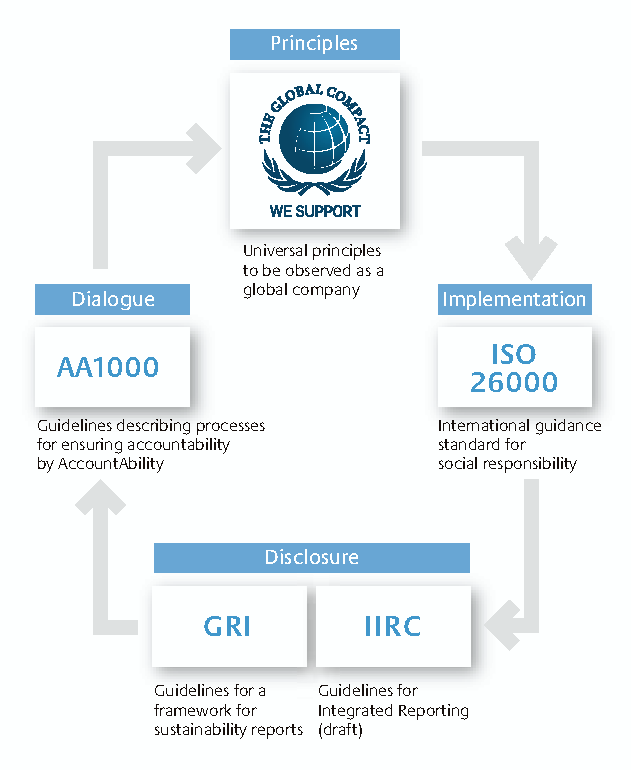

Its initiatives are quite transparent to the public (Figure 4): Its basic principles are informed by the Global Compact; analysis and implementation are guided by ISO 26000; disclosures are made in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative; and accountable dialogue is advanced based on the AA1000 guidelines of Britain’s AccountAbility.

Figure 4. CSR Guidelines for Reference

Some companies may prefer to use their own standards. But international guidelines like the Global Compact and ISO 26000 offer the benefit of expertise accumulated through dialogue with stakeholders around the world. Takeda makes active use of these public resources—something made possible by the thorough understanding of these guidelines by its CSR officers.

Addressing Social Issues through the Value Chain

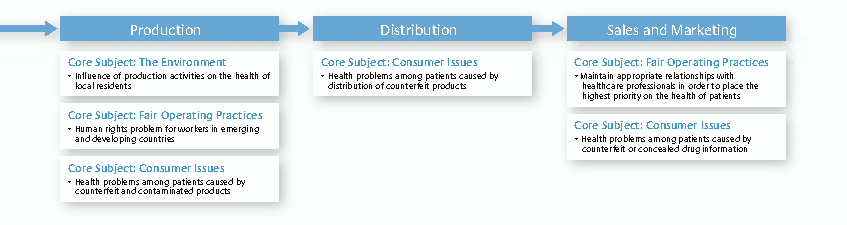

Takeda skillfully utilizes the guidelines to identify and address various social issues through the value chain. Gaining a grasp of a full range of social issues on one’s own can be a daunting task, so the company refers to the seven “core subjects” of ISO 26000 in analyzing its social responsibilities to both help create and sustain corporate value (Figure 5).

One core subject is human rights. Takeda highlights possible issues along the value chain, from research and development (including clinical trials) to procurement, production, distribution, and sales and marketing, so that each department has a full awareness of what to keep in mind.

For example, the research department conducts its activities in line with a set of policies and rules aimed at respecting dignity and human rights. Specifically, a Research Ethics Investigation Committee has been set up to deliberate on issues like the use of such human-derived specimens as blood, tissue, and cells.

Figure 5: Addressing Core Subjects in the Value Chain

To address issues in procurement, production, and distribution, meanwhile, the company established a Global Purchasing Policy and Guidelines for Socially Responsible Purchasing calling for the rights of all people to be respected and the elimination of discriminatory or unfair practices based on nationality, race, ethnicity, creed, religion, gender, age, disability, disease, or social status. In addition to rooting out discrimination in its own operations, Takeda shares these principles with its suppliers and encourages their implementation.

The important thing is to think ahead in identifying relevant issues and considering what action to take. Most companies surveyed or interviewed by the Tokyo Foundation for the white paper had few initiatives regarding human rights other than organizing conventional workshops for employees.

Only when these issues are fully incorporated into the value chain, as Takeda has done, though, will they be perceived as being part of a company’s routine business operations.

Vaccines to Fight Communicable Disease s

In its efforts to create corporate value, Takeda prioritizes two CSR material issues: “access to healthcare” and “value chain management.” The latter has been described above, so the former will be discussed here.

Access to healthcare refers to the broad range of initiatives aimed at enhancing the availability of healthcare services for people around the world. Part of this effort involves addressing unmet medical needs—situations where medical services are locally unavailable or where effective treatment does not yet exist. This can mean dealing with situations in developing countries where economic conditions prevent people from receiving existing vaccines or treatment and also cases in richer countries where preventative medicine or treatment has not yet been developed.

Many people around the world still die from communicable diseases for which vaccines already exist. Takeda thus aims to become a top vaccine manufacturer by 2020 by enhancing its R&D, approval, and sales efforts in key markets for vaccines considered to be public-health priorities.

In addition to investing in its own research efforts, Takeda has moved to acquire companies with promising pipeline drugs. In October 2012 Takeda purchased LigoCyte Pharmaceuticals, a company working on a vaccine for the norovirus. The biotechnology company specialized in the development of new vaccines using their proprietary virus-like particle technology. Norovirus is the primary cause of gastroenteritis and food poisoning in developed countries, making 21 million people ill each year; in developing nations it causes 200,000 deaths a year.

In May 2013 Takeda also purchased Inviragen, a company developing vaccines for dengue fever and hand, foot, and month disease. A mosquito-borne disease, dengue fever is a serious ailment in developing countries for which no effective treatment currently exists—despite the fact that 400 million people are infected each year, with around 100 million developing symptoms. The World Health Organization identifies dengue fever as one of four diseases urgently requiring a vaccine.

Taking these social needs into account, Takeda is allocating ample resources to the development of pipeline vaccines, including through mergers and acquisitions. By carefully considering its relationship with society Takeda has been able to more sharply define its corporate mission and enhance the value of its main business operations. This, too, is CSR that creates corporate value.

Disaster Relief and Takeda-ism

Some may unfavorably liken Takeda’s recent acquisitions to the activities of an investment bank. But a closer look reveals that they are attempts to both create and sustain corporate value through a vigilant focus on the company’s corporate mission, risk management, and its relationship with society.

Informing the decisions of both managers and staff is a long-standing corporate philosophy known as Takeda-ism that pervades the company’s operations (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Takeda-ism and Values

At the heart of Takeda-ism is integrity—that is, fairness, honesty, and perseverance. Around these core values are such principles as diversity, teamwork, commitment, transparency, innovation, and passion, which are upheld in one’s daily activities. Takeda employees are thus called upon to strive toward integrity in all aspects of their work. Integrity means compliance with the highest ethical standards and a basic stance of fairness and honesty. It also requires a spirit of perseverance focused on constant improvement.

This philosophy of integrity was evident following the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011. Takeda cooperated with the recovery efforts of the Japan NPO Center in two ways: providing grants to nonprofits and other groups directly engaged in reconstruction and implementing projects either independently or with partners.

Takeda’s assistance for NPOs was aimed at supporting the day-to-day lives of survivors—particularly vulnerable members of society like children, the elderly, people with disabilities, disaster orphans, those who lost family and relatives, and people in financial difficulties—so they may live with dignity. These efforts were aimed at rebuilding people’s lives by improving health and welfare conditions and also at rebuilding livelihoods by offering places to live and work. Estimating that the recovery would take about a decade, Takeda is maintaining these support programs through 2020.

The five projects implemented by Takeda and with partners—all with an emphasis on cultivating human resources—demonstrate the company’s philosophy even more clearly. It has (1) established the Japan Civil Network for information sharing among disaster relief groups; (2) analyzed the progress and trends in private relief efforts with the Japan NPO Research Association; (3) worked with groups in three disaster-hit prefectures engaged in supporting disabled people and providing related services; (4) supported people who lost family members with Lifelink, a suicide-prevention NPO; and (5) promoted information sharing on reconstruction assistance measures and issued proposals on ways to improve those measures with the Coalition for Legislation to Support Citizens’ Organizations (C’s).

All five projects have close links to networks for the reconstruction of disaster-hit areas. They seek to assess civil-sector assistance to date and offer a prognosis for the future in an attempt to build a foundation for smoother communication among the various groups—a foundation focused not on systems or infrastructure but on people on the ground.

This person-centered approach is typical of the company’s reconstruction assistance and its CSR initiatives as a whole. Creating and sustaining corporate value is really all about people. Many companies ponder what they should achieve through CSR and how should it should be integrated into their business operations. Takeda’s efforts provide one answer to such queries.