- Article

- Fiscal Policy & Social Security

Japan’s Thorny Path to Fiscal Consolidation

December 25, 2014

Although Prime Minister Abe’s decision to postpone the planned hike in the consumption tax was popular with voters, resulting in a commanding majority for his coalition government in the December 2014 lower house election, it could spell trouble further down the road for the nation’s public finances. Prescriptions for fiscal consolidation are quite simple, but politics, argues Senior Fellow Sota Kato, will likely get in the way of any serious attempts to restore fiscal health.

* * *

In his November 18, 2014, press conference, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced he was postponing a hike in the consumption tax from 8% to 10%—scheduled for October 2015—for 18 months, given the fragile state of the economy. He then told the nation that he was dissolving the lower house of the National Diet to seek a mandate on his decision.

Not surprisingly, the December 14, 2014, snap election for the House of Representatives resulted in a landslide victory for Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party, giving the LDP and its coalition partner Komeito more than a two-thirds majority in the lower house.

Although the postponement was popular with the public, it risks exacerbating Japan’s overly strained finances. Without additional revenues, Japan’s already abnormally high government debt will continue to balloon out of control. Many economists, both in Japan and abroad, have contended that debt levels are not yet dangerous enough to cause alarm. But budget figures paint a rather scary picture. Japan’s outstanding public debt already exceeds 200% of gross domestic product and is approaching 240%—by far the worst of any Group of Seven country.

The future looks even bleaker. A fiscal projection by a group of Japanese economists and announced by Keidanren in 2012 shows that Japan’s public debt could skyrocket to nearly 600% of GDP in 2050—and this forecast was made on the assumption that the consumption tax would be raised to 10% in 2015, as scheduled. This is a level that no advanced democracy in the world has ever experienced. The economists then calculated the consumption tax rate that would be necessary to keep debt at the current level (that is, 240% of GDP). The figure they came up was 24.7%, which is much higher than the 10% that Prime Minister Abe postponed.

Three Paths

What would Japan need to do to embark on the path of fiscal consolidation? The answer is actually quite simple, for there are only a handful of possible scenarios. The first path would be to just grow the economy, the second to hike taxes, and the third to cut spending. I will examine these three paths one by one.

The first path of simply growing the economy is what economists and politicians close to Prime Minister Abe have been advising. This is a simple idea of allowing economic growth to solve the debt problem by itself, with stronger profits leading to increased tax revenues. Advocates of this view believe that if Japan managed to grow like it did in the 1980s, the public debt problem would disappear. This would be a wonderful scenario for everyone if it were possible, but it could turn out to be very difficult to achieve.

The first and most obvious question is, how can Japan return to high-paced growth after decades of stagnancy? Paul Krugman of the New York Times shows that Japan’s economic performance, adjusted to its demographics, is surprisingly strong, compared to the United States. While Japan lagged behind the United States and European countries in terms of real GDP growth, it was roughly even in terms of per capita GDP and even outperformed them in figures for per working-age adult. So Japan might actually have done pretty well if it managed to control its demographics.

The flip side of this finding is that given the rapid aging of the population, there might be very little room for growth in Japan. Unless the Japanese population can suddenly start growing again—or unless the economy’s productivity can be radically improved—achieving success on the first path will be more difficult than one might imagine.

What are the major obstacles to path-one growth? The first is insufficiency; a long-term estimate published in 2014 by the Japanese government’s fiscal council shows that even if we optimistically assume a 3% annual growth rate for nominal GDP, this will not be enough for fiscal consolidation. There will also be a need to increase taxes and cut spending. Another is uncertainty, meaning that no one has a clear idea of what it would take to achieve strong growth. Sticking with this path in the hope that the Japanese economy will grow—and refraining from increasing taxes or cutting spending—would be very risky. The third obstacle is politics and the tendency of politicians to avoid structural reforms that are resisted by vested interests.

Higher Taxes

The second of the three paths to fiscal consolidation is to increase taxes, which Prime Minister Abe just postponed. It is important to note that Japan’s consumption tax rate and tax burden are some of the lowest among countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. So there would appear to be room for substantial increases in the tax rate. Economic simulations have shown that Japan needs to jack up the consumption tax to 20% or even 40% in order to lower the fiscal deficit. American economists R. Anton Braun and Douglas Joines report that it would take nearly a century to consolidate Japan's fiscal situation.

The chief obstacle here, as the election results clearly demonstrate, is politics. Would a 20% to 40% consumption tax rate be a realistic political option in Japan, where 67% of the electorate are opposed to even a 10% rate? The political problem is a very difficult one, for several prime ministers who proposed raising the consumption tax have been driven out of power.

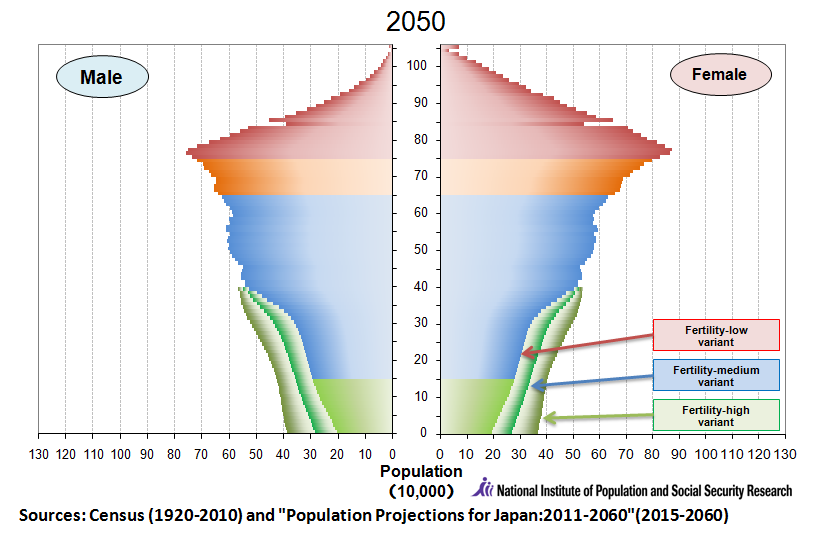

What are the prospects of the third path—cutting spending? Currently, 30% of the national budget is allocated to social security payments. As the aging of society proceeds, this percentage will steadily continue to rise. This suggests that spending cuts should be focused on social security payments.

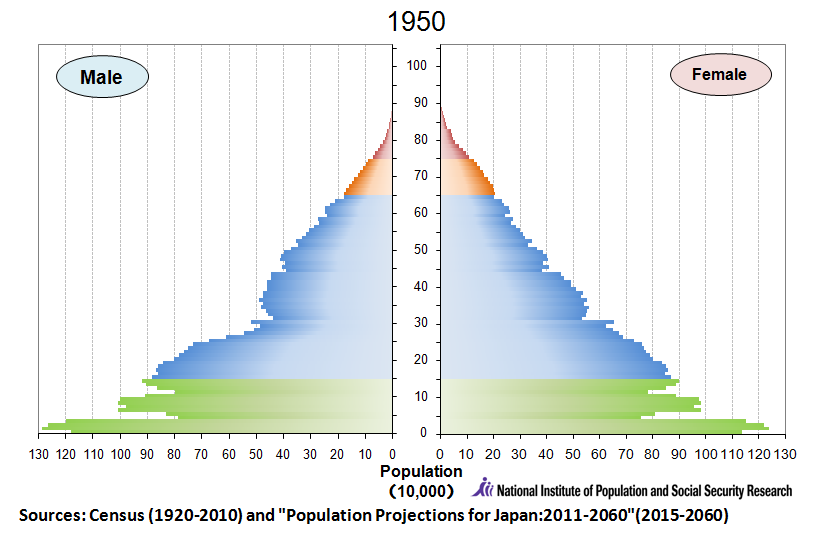

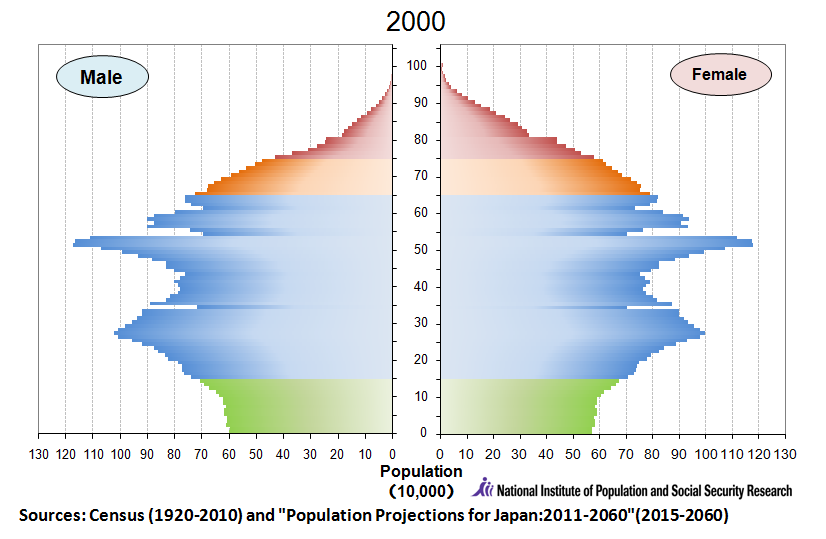

Japan's Population Pyramid, 1950, 2000, and 2050

Japan’s demographics have changed drastically over the past half century. In the 1950s, the population pyramid was really a pyramid. But by 2000, the base of the pyramid shrank, reflecting the lowering of the birthrate. In 2050, the pyramid is projected to appear upside down. The social security system has not absorbed this change, however, so there is a great mismatch between demographics and the social security payment system.

A balance must be struck between social security benefits and burdens. The obstacle, again, is politics. Japanese politicians will tell you that cutting social welfare spending is even more difficult than increasing taxes. So expecting politicians to fix the fiscal debt problem could prove to be asking for the impossible.

The landslide election victory was a vote of confidence for the prime minister to vigorously advance his Abenomics agenda. We would hope that Abe uses the mandate to achieve breakthroughs on such politically difficult problems as the need for structural reforms, higher taxes, and a lowering of social benefits.